I’ve been working on my genealogy for about twenty years now. When I started out there was no internet and therefore no online data, so the only way to build verified information was to visit record offices and libraries. As my mobility became worse by lucky coincidence internet access improved and the range of online data grew. Today nearly all crucial historic data is online.

I’ve been working on my genealogy for about twenty years now. When I started out there was no internet and therefore no online data, so the only way to build verified information was to visit record offices and libraries. As my mobility became worse by lucky coincidence internet access improved and the range of online data grew. Today nearly all crucial historic data is online.

My research has revealed staggering stories not unlike millions of others who for generations lived basic and desperate lives in the UK before the 20th century. It was wasn’t until well into the industrial age that some of my relatives dropped the shovel, left the fields, relocated and worked on the railways.

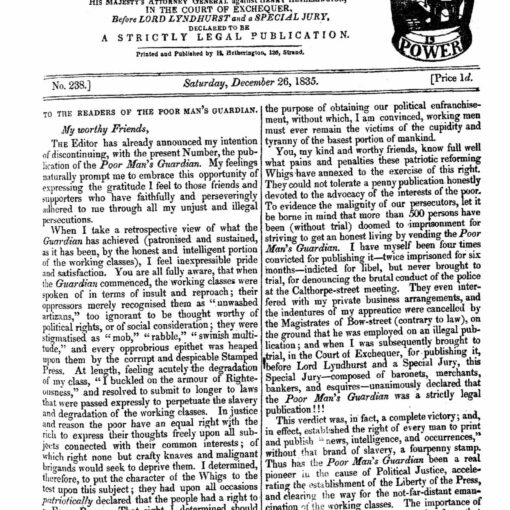

Some took the break with tradition and worked desperately hard to create a better life for their loved ones which placed their family on a better track for the future towards our modern age. The story of the Waughs, the Churchwards, the Caves, the Woodroffs and the rest of those connected directly with my family differ little from thousands of other British families over generations that led lives so comparatively basic.

Even as late as the 1890s there remains horrific and deeply haunting stories that have recently been revealed through my research. My poor great grand aunt who was an octogenarian in 1891 and even at her old and frail age was still scrubbing the floors of residents in Newton Abbot. Then the family of about half a dozen children who resorted to living in the workhouse because after their young father had died. In 1871 the indelible census archive cruelly labels them ‘paupers’. By 1881 the mother of this family, who had given birth and lost her child in the workhouse, had struggled to find a job as a nurse and had managed to get her family out of the workhouse. By doing so she historically removed the word, the stigma, “pauper” from her family name. Some in my family were not quite so lucky and ended up living in the workhouse and finally dying there.

I am proud of my ancestors whether they are cabinet makers, horse grooms, carpenters, agricultural labourers, miners, boiler makers, copper-smiths, servants and even labeled paupers – they are my blood, my DNA.

Through the branches and generations of my family all sorts of stories reveal themselves through proven and double verified data. Indeed out of the more than 1200 direct blood relatives now attached to my family tree I can safely say that every single connection has been checked and double checked. But amongst the sea of ‘ordinary’ folk there are one or two interesting matters that on the surface I find strangely disturbing.

The fact I can trace one direct blood branch of my family back to 1475, the thing it can be proved and a double proved, is in its way quite disturbing and a little haunting. On the one hand it’s quite a delightful revelation but on the other I feel that my blood now goes back to an age that I know so very little and is now in research terms so very distant.

538 years ago is by anybody’s estimation a very long time ago. We are, most of us anyway, nothing particularly special but being ordinarily is important. My family come from fairly lowly, but seemingly average, British stock is a matter that I am deeply proud of. It is stuck to me, it is part of my DNA, my blood – it is who I am.

Every week I am unraveling stories about my family in the Georgian and Victorian times and in each of these tales the common thread is the fact that nearly all of these people struggled to survive with a undeniable strength and determination that personally brings a determination and understanding of what came before. It is that very thing that gives me strength and an overriding understanding that we are lucky to be alive no matter of our age or health.