The Morning Post – Wednesday 31 March 1830

This article describes an event reported in The Morning Post newspaper, dated 31 March 1830. It recounts a shocking and socially disgraceful incident that took place in a crowded marketplace. In summary, the article portrays a deeply degrading episode in which societal norms, gender inequality, and public morality collide. It serves as both a reflection of the time’s social challenges and a critique of the behaviours that undermined the dignity of individuals, especially women.

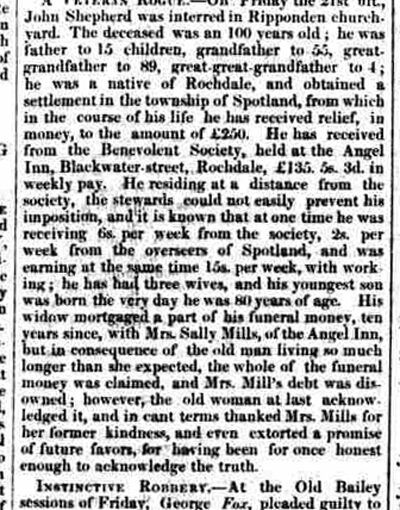

DISGRACEFUL OCCURRENCE. — On Thursday last, while the corn market was crowded with respectable farmers, a fellow dishonoured the name of civilised man by offering his wife for sale. We understand a sweep offered sixpence by way of joke; but the purchase was not absolutely made, as the woman, who had been inveigled into the market and a halter thrown round her neck before she was aware, fled from the scene of degradation, and her husband had some difficulty in escaping the chastisement of the pump. The police, however, were speedily on the look out to prevent a recurrence of the auction or its consequences. — (Ibid.)

Detailed Contextual and Historical Explanation:

1. The Article and the Event:

- The article recounts a “disgraceful” and unusual event that took place in Cheltenham, a market town known at the time for its agricultural fairs and commerce. It describes a man attempting to sell his wife in a public corn market.

- The incident highlights both the public nature of wife-selling and the social condemnation it received, even in a time when legal divorces were expensive and inaccessible to many working-class individuals.

2. Cheltenham and Its Corn Market:

- Cheltenham in 1830: Known for its affluent spa culture, Cheltenham was a hub for both the gentry and the farming community. Corn markets were central to agricultural trade and would have attracted a wide spectrum of people.

- The corn market was likely bustling with merchants, farmers, and townsfolk when this incident unfolded, making it a highly public event.

3. Practice of Wife-Selling:

- While selling a wife was not legally recognised as a form of divorce, it was sometimes a folk tradition among the working class. The practice usually involved the public transfer of a wife from one man to another, symbolised by the use of a halter (rope or strap) around her neck. However, this was socially contentious and not widely accepted.

- In this case, the wife was tricked into the market (“inveigled”) and subjected to public humiliation against her will. The man’s actions were seen as dishonourable, even within the loose conventions of wife-selling.

4. Public Reaction:

- A chimney sweep jokingly offered sixpence for the woman, emphasising the absurdity and degradation of the situation. However, the transaction did not proceed, as the wife fled the market after realising what was happening.

- The public turned on the husband, and he narrowly escaped being physically punished (“the chastisement of the pump”). This phrase likely refers to the tradition of using a water pump to drench or humiliate wrongdoers in public.

5. Police Involvement:

- The police were quick to intervene to prevent further disturbances. This shows that while informal wife sales occurred, they were not legally sanctioned and were often policed to avoid escalating social unrest.

6. Social and Historical Implications:

- This incident serves as a window into the tensions of 19th-century English society, particularly regarding class, gender, and morality.

- Gender Inequality: The event underscores the lack of agency and dignity afforded to women in the lower socio-economic strata. The wife had no control over her situation and was treated as property.

- Class Dynamics: The man’s behaviour was condemned by “respectable farmers,” who represented a more affluent and socially conscious demographic within the marketplace. The event was seen as a breach of public decency.

- Legal Context: Divorces at the time required a private Act of Parliament and were prohibitively expensive. Wife-selling, though illegal, was an informal way for some to end marriages, particularly in rural or working-class communities.

7. The Morning Post’s Perspective:

- The Morning Post was a well-established London-based daily newspaper at the time, known for its coverage of domestic and international news, advertisements, and reports on social issues.

- By framing the incident as a “disgraceful occurrence,” the newspaper reflects middle-class morality and disdain for behaviours that undermined the image of a “civilised society.”

8. About the Morning Post:

- The Morning Post began publication in 1772 and evolved over time, merging with other newspapers such as the Gazetteer and later the Daily Telegraph in 1937. Initially focusing on advertisements and notices, the newspaper grew to include domestic and international news, with a focus on high society and literary contributions.

- By 1830, under the ownership of figures like Daniel Stuart and others, the Morning Post balanced news with reports on fashionable society. Its condemnation of the Cheltenham incident aligns with its aspiration to cater to a more refined readership.

Conclusion:

This article vividly captures a moment of societal discord in early 19th-century England. The act of selling a wife, while an informal practice rooted in economic and social constraints, was met with public outrage and legal oversight. The Morning Post’s reporting not only sheds light on the event but also reflects the shifting moral expectations of its readership during a time of social and legal transformation.

The Morning Post Newspaper:

The Morning Post and Daily Pamphlet began publication in 1772, quickly changing its title to the Morning Post or Cheap Daily Advertiser. By early 1773, the title was altered to the Morning Post and Daily Advertiser—a name it retained until 1792. With the issue dated 15 December 1792, the title was further simplified to the Morning Post.

The newspaper’s early proprietors included John Bell, a printer and bookseller, and James Christie, an auctioneer. Christie utilised the newspaper to advertise his upcoming auctions. During its first twenty years, the newspaper was published daily on four large folio pages, with at least two-thirds devoted to advertisements and notices. These advertisements covered a wide range of topics, including forthcoming theatre performances, newly published books, patent medicines, properties to let, horses for sale, furniture auctions, pictures, and a variety of other goods and services. The remaining pages focused on domestic news, with only a few paragraphs dedicated to international events.

John Bell sold his stake in the Morning Post and Daily Advertiser in 1786. The following year, he founded the World and Fashionable Advertiser. Bell sold his interest in this new publication in 1792, and in 1794, the World (as it was then known) merged with the Morning Post to form the Morning Post and Fashionable World. The first issue under this new title was published on 1 July 1794. It described its predecessor publications as “firm, moderate, and independent” newspapers, and proclaimed itself “pre-eminently distinguished for its foreign intelligence, and for an elegant and polished domestic miscellany.” Despite these lofty ambitions, the circulation of the Morning Post and Fashionable World dwindled rapidly.

In 1795, the paper was purchased by journalist Daniel Stuart, who broadened its coverage and revived its fortunes. Stuart introduced articles on parliamentary reform and defended the French Revolution, while also reporting on fashionable society and giving considerable space to advertisements. Under his direction, the newspaper serialised Thomas Paine’s Decline and Fall of the English System of Finance shortly after its publication in 1796. Stuart also attracted new writers, including the poet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

On 20 September 1797, the Morning Post and Fashionable World announced its acquisition of the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser. The issue dated 2 October 1797 was published under the title Morning Post and Gazetteer. Stuart remained the proprietor, and the newspaper continued its mix of domestic and international news, high-society reporting, and advertisements, which occupied the first and last pages of its four folio sheets.

In 1803, Stuart sold his interest, and the Morning Post and Gazetteer entered another period of decline. However, the paper managed to recover and persisted—under the shortened title Morning Post—until 1937, when it merged with the Daily Telegraph.