THE ANTIQUARIAN ROMANCE.

MORE REMARKABLE EVIDENCE.

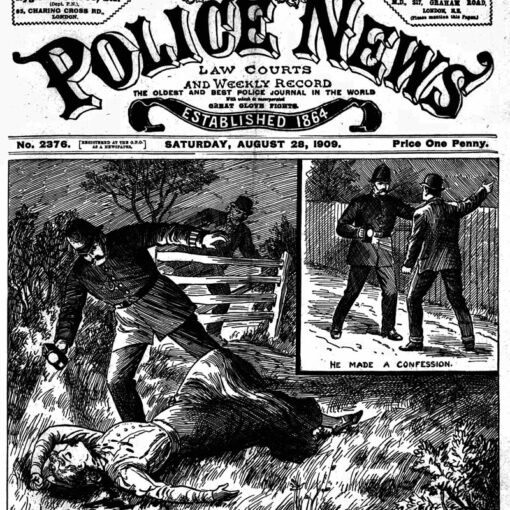

Mr. Lushington sat again specially at Bow-street yesterday for the further hearing of the charges against Herbert Davies, twenty-five, “private surgeon,” of Castlenau-gardens, Barnes, of forging entries in Mangotsfield parish register, tampering with monuments and coffins, forging three sixteenth-century wills, and making a false statutory declaration, with the object of deceiving his employer, Colonel Shipway, as to his pedigree. Mr. Bodkin, instructed by Mr. Brown, of the Treasury, prosecuted; Mr. H. T. Waddy defended; Detective-inspector Brockwell represented the police.

COLONEL SHIPWAY RECALLED.

Colonel Shipway, recalled, said that about February 1896, he received from the prisoner a silver watch bearing the inscription “William Shipway, 1763; Dum Vivo.” The witness made some inquiries about the maker of the watch and also the hallmark. He found that the mark was that of 1782-83. The witness asked the prisoner to account for the discrepancy, and he said that the watch had been sold to him at Stroud, in Gloucester, by someone who had bought it at an auction. The witness told him to question the man who had sold him the watch, and to communicate with Messrs. Witchell, solicitors, of Stroud, who were acting for the witness. They wrote to him, and then Davies gave him a letter dated March 23, signed “A. Blackwell,” and addressed from 17, Westgate-street, Gloucester. The writer, addressing Davies, said that this watch was one of a lot of twenty which he bought at an auction in Birmingham in 1888 for £2 5s., intending to melt them down for the sake of the silver. He did not notice the inscription at the time, but when Davies wanted to buy it his son cut it deeper. The writer concluded by saying he would write to the auctioneer and send on his reply. The witness paid 30s. to the prisoner for the watch.

In cross-examination by Mr. Waddy, the witness said that he never knew that Davies held a degree or was a doctor, so that this did not influence the payments. The witness had no doubt that the prisoner did a great deal of work in his behalf in the nature of research, and the witness made no complaint as to the payments for this. The witness never promised him any sum if he succeeded in establishing his coat of arms.

The Shipway Pedigree Scandal of 1898 is a remarkable case of genealogical fraud that exposed the lengths one man would go to fabricate history for personal gain. Herbert Alfred Davies, a self-proclaimed genealogist, manipulated historical records, forged documents, tampered with graves, and falsified artefacts to construct an elaborate but fraudulent family pedigree for his employer, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert William Shipway. Driven by financial gain and a desire to enhance his own reputation, Davies created a web of deceit involving forged parish records, fabricated wills, and desecrated tombs to portray the Shipway family as noble descendants worthy of heraldic recognition. When his forgeries were uncovered by experts, the case became a sensational court trial that highlighted the vulnerabilities in historical research and underscored the importance of preserving the integrity of archival and genealogical records.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Mangotsfield Forgeries: A Scandal of False Pedigrees and Opened Graves

By Ian Waugh

In the autumn of 1898, an extraordinary case of deception and fraud captivated the British press, centring on a self-proclaimed genealogist and his audacious scheme to fabricate history. Herbert Alfred Davies, a 25-year-old from Barnes, faced charges of forgery, grave tampering, and fraud at Bow Street Police Court. His victim, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert William Shipway of Chiswick, had trusted Davies to uncover his family’s heritage, only to be duped into paying nearly £700 for falsified documents and fraudulent claims. Dubbed “The Shipway Pedigree Scandal,” the case uncovered a tangled web of deceit that extended from dusty parish registers to desecrated graves.

The Colonel’s Quest for Ancestry

In 1895, Lieutenant-Colonel Shipway began his search for historical connections to his Gloucestershire roots. While he expressed no intention of seeking arms or titles, he engaged Davies, a purported expert in genealogy, to trace his family lineage. Promising skills in Latin and historical research, Davies was hired at six shillings a day, plus expenses.

Initially, Davies focused on Gloucestershire’s parish records, guided by a tenuous mention of a “Shipway” in a local history book. The book referred to a 17th-century farmer named Nicolas Shipway, associated with Beverstone Castle near Tetbury. Though unremarkable, this connection became the seed of Davies’s increasingly elaborate deceptions.

From Parish Registers to Grand Inventions

Fabricated Records

Davies claimed to discover six Shipway entries in the Mangotsfield parish registers, including baptisms, marriages, and burials spanning the late 16th and early 17th centuries. One entry stood out: the burial of “John Shipway” in 1625, accompanied by the Latin phrase Sigillum Leo telo manus (Seal of the Lion with Weapon in Hand). This supposedly indicated a family crest.

What Davies failed to anticipate was the existence of an earlier, complete transcription of the registers made in 1720, which contained no such entries. This evidence, later unearthed by experts, proved critical in dismantling his claims.

The False Seal

Among Davies’s many fabrications was a seal bearing a lion rampant. He asserted it had been passed down by a Shipway ancestor through a sexton at Mangotsfield Church. Davies even presented a statutory declaration from a “witness” to corroborate its authenticity. In reality, the “witness” was none other than Davies himself, masquerading under an assumed identity.

Forged Wills

To bolster his fabricated pedigree, Davies created three fraudulent wills. One, dated 1547, described an ancestor receiving a grant of arms from Richard I in 1191—a glaring historical impossibility. Experts later discovered that one will was a forgery written over an erased original, with remnants of the original testator’s name still visible.

Desecrating the Dead

In November 1896, Davies embarked on his most egregious acts: tampering with graves in Mangotsfield churchyard. Under the guise of historical research, he obtained permission from the Home Office to open graves, provided no remains were disturbed. This condition was blatantly ignored.

- Grave Manipulation: Davies exhumed a lead coffin inscribed “Hicks” and etched the name “John Shipway” alongside Leo telo manus using acid. The Hicks coffin was then relocated, and a nameless tombstone was placed over its original grave.

- Fatal Consequences: During the grave tampering, a labourer named Frederick Webster was fatally injured. Davies misappropriated most of the compensation intended for Webster’s widow, giving her only £4 out of the £10 provided by Shipway.

Elaborate Monumental Hoaxes

Inside Mangotsfield Church, Davies continued his fraudulent campaign:

- Effigy Alterations: Davies unearthed a buried stone effigy, claiming it represented “John Shipway, Man of Arms of Mangotsfield.” He carved initials into the figure’s breastplate and placed it in a glass case, inscribed as a gift from Colonel Shipway.

- Belfry Engraving: Locking himself in the church belfry, Davies carved “John Shipway, 1541” into a beam. Parish workers noted the sudden appearance of the inscription, which was written in a modern style.

Unravelling the Deception

Colonel Shipway’s growing unease led him to consult W.P.W. Phillimore, a respected genealogist. Phillimore quickly exposed discrepancies in Davies’s findings:

- Forgery Detection: The supposed wills and parish entries were riddled with inconsistencies, including modern spellings and stylistic errors.

- Probate Records Tampering: Davies had replaced original wills in the Gloucester diocesan archive with his forgeries. In one case, traces of the original will’s text were still visible beneath his additions.

Phillimore’s findings were forwarded to the Director of Public Prosecutions, resulting in Davies’s arrest in September 1898.

The Trial and Verdict

Over several hearings at Bow Street Police Court, the full extent of Davies’s fraud came to light. Witnesses included:

- John Priddy (Parish Clerk): Testified that no Shipway references existed in the parish before Davies’s involvement.

- Albert Silbery (Engraver): Admitted to distressing modern objects at Davies’s request to make them appear antique.

- Experts in Historical Documents: Highlighted anachronisms and modern idioms in the forged entries and wills.

In November 1898, Davies pleaded guilty to eight counts of fraud and forgery at the Old Bailey. Despite pleas for leniency, citing his young family, he was sentenced to three years of penal servitude.

Aftermath

The fraudulent monuments and inscriptions at Mangotsfield Church were removed, and the parish registers were corrected with explanatory notes. The Bishop of Bristol oversaw the restoration of the church to its original state.

Davies was released from prison by 1901. He later worked as a soldier in the Royal Army Medical Corps and eventually as a draper’s manager. Though his crimes left a stain on genealogical research, he seemingly avoided further scandal in his later life.

A Legacy of Caution

The Shipway Pedigree Scandal remains a cautionary tale in the annals of genealogy. It highlights the importance of verifying sources and the damage wrought by unchecked ambition. For researchers and enthusiasts alike, the case underscores the need for vigilance in preserving the integrity of historical records.

Detailed Examination of the Shipway Fraud Case

Background

In 1895, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert William Shipway of Grove House, Chiswick, sought to trace his family lineage. His aim was to explore the family’s history in Gloucestershire, without initially intending to claim heraldic rights. Shipway was introduced to Herbert Davies, a 25-year-old claiming to be a “surgeon” and an Oxford graduate. Davies falsely represented himself as an expert in genealogy and heraldry, persuading Shipway to hire him at 6s per day, plus expenses, to conduct the research.

Davies’s fraudulent scheme unfolded over two years, ultimately exposing weaknesses in historical and genealogical practices of the time.

Fraudulent Activities

1. Forging Parish Records

- Davies tampered with parish registers to fabricate evidence of the Shipway family’s distinguished ancestry.

- Example: In the Mangotsfield parish register, he created an entry stating “Johannes Shipway, man of arms, baptised July 6, 1579.” This entry was written in inconsistent Latin and differed stylistically from other entries, exposing it as a forgery.

- Davies also inserted false marriage entries, such as one for “John Shipway” in 1591. These entries mixed Latin and English, a clear anachronism for the period.

2. Fabrication of Wills

- Davies forged three sixteenth-century wills, purporting to trace the Shipway family to medieval nobility.

- Key example: The will of “John Shipway (1547)” claimed lineage back to a grant of arms by Richard I in 1191. However, historical inaccuracies undermined this claim, such as Richard I being in Palestine at the time.

- Experts revealed that the handwriting across the wills was identical and inconsistent with genuine sixteenth-century documents.

3. Grave Tampering

- Davies sought physical evidence to reinforce his fabrications:

- He exhumed graves in Mangotsfield churchyard under false pretences, claiming he was conducting historical research.

- Davies moved a lead coffin marked “Hicks” and etched the inscription “Job Shipway, 1628” onto it. Evidence showed the inscription was recent, with witnesses noting the smell of acid in the vestry.

- During one excavation, a labourer, Frederick Webster, was fatally injured. Davies pocketed £6 of the £10 given by Colonel Shipway to compensate Webster’s widow.

4. Altering Monuments and Artefacts

- Davies manipulated existing artefacts to create a narrative:

- He engraved “John Shipway, 1541” onto a church beam in the Mangotsfield belfry, which was later proven to be a nineteenth-century carving.

- He fabricated inscriptions on a stone shield, changing “Andrews” to “Shipway.”

- An iron hasp was engraved with “Ye Giffte of I. S.,” falsely suggesting a historical donation.

5. Presenting Falsified Evidence

- Davies submitted photographs and “authentic” discoveries to Shipway, who forwarded them to the College of Arms. When the College requested more substantial proof, Davies forged additional documents and tampered with wills held in Gloucester and Worcester diocesan registries.

Legal Proceedings

Initiation of the Case

- Doubts about Davies’s claims arose when Shipway consulted W.P.W. Phillimore, a respected genealogist. Phillimore identified glaring inconsistencies in the documents, prompting Shipway to report Davies.

- The case proceeded to trial, with Mr. Bodkin prosecuting on behalf of the Treasury. The case became a state prosecution due to its severity and implications.

Evidence Presented

- Testimonies from Witnesses:

- John Preddy (Mangotsfield Parish Clerk):

- Confirmed that the Shipway name was unknown in the parish before Davies’s involvement.

- Noted that inscriptions, such as “Johannes Shipway,” appeared in the church only after Davies’s arrival.

- Albert Silbery (Engraver):

- Admitted to engraving items for Davies, including the shield and the hasp, at Davies’s explicit instruction to make them appear antique.

- Joseph Coles (Bellringer):

- Testified that the “John Shipway, 1541” carving was newly created and inconsistent with genuine historical inscriptions.

- John Preddy (Mangotsfield Parish Clerk):

- Physical and Photographic Evidence:

- Photographs of altered documents and artefacts highlighted discrepancies, including modern handwriting styles and erased or re-written text.

- A coffin bearing the inscription “Job Shipway, 1628” showed clear signs of recent tampering.

- Expert Testimony:

- Document analysts highlighted the use of modern idioms and anachronistic Latin in the forged entries.

- Antiquarians identified stylistic inconsistencies in the fake wills, noting that they were written by the same hand.

Legal Arguments

- Prosecution:

- Argued that Davies’s actions constituted wilful fraud, deception, and forgery, causing financial and reputational damage to Colonel Shipway.

- Emphasised the broader harm to public trust in historical records.

- Defence:

- Suggested that some errors might have been unintentional and questioned whether Davies alone was responsible for all the fabrications.

- Outcome:

- Davies pleaded guilty under overwhelming evidence and was sentenced to three years of hard labour.

Broader Historical Implications

- Impact on Genealogical Research

- The case highlighted the need for rigorous scrutiny in genealogical studies. It exposed vulnerabilities in historical records, where false entries could be inserted with little oversight.

- It also underscored the importance of expert verification in assessing claims of noble or heraldic ancestry.

- Awareness of Fraud in Historical Documentation

- Public interest in the trial brought attention to the potential for forgery in archival research.

- Institutions began re-evaluating the security and authenticity of records, leading to more stringent preservation practices.

- Legal Precedent

- The case reinforced the seriousness of forgery and fraud, particularly in matters involving public and historical trust.

- It set a precedent for holding individuals accountable for tampering with historical artefacts and records.

- Public Perception of Genealogy

- The trial revealed the ease with which ambitious claims of noble ancestry could be fabricated, cautioning individuals against placing blind trust in researchers.

- It spurred greater interest in legitimate genealogical research and raised standards in the field.

The fraud perpetrated by Herbert Davies against Lieutenant-Colonel Shipway remains a cautionary tale in the realms of history and genealogy. The meticulous legal case demonstrated the importance of safeguarding historical integrity and holding perpetrators of fraud accountable. The implications of the case extend beyond the courtroom, influencing archival practices and public understanding of genealogical research to this day.

Free to use British Newspaper Research Service

British newspapers offer a treasure trove of information for family historians. They capture moments in time, providing context, character, and community insight that official records cannot. With the free service provided by Old British News, this research becomes even more accessible, enabling historians to delve into rich, untold stories of their relatives. By combining these resources with other records, family historians can create a more complete and engaging picture of the past.

I search historical articles to locate mentions of your ancestors—whether they were involved in notable events or simply part of the everyday life reported in these newspapers. If relevant articles are found, I deliver them to you in a PDF format at no cost.

If I find articles, they’ll be sent to you in a clear, organised PDF. If not, you’ll be informed right away. See here.