Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday, 3 August 1811

Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday, 3 August 1811

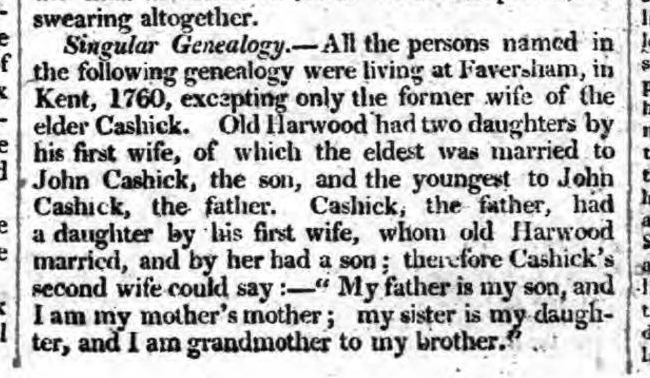

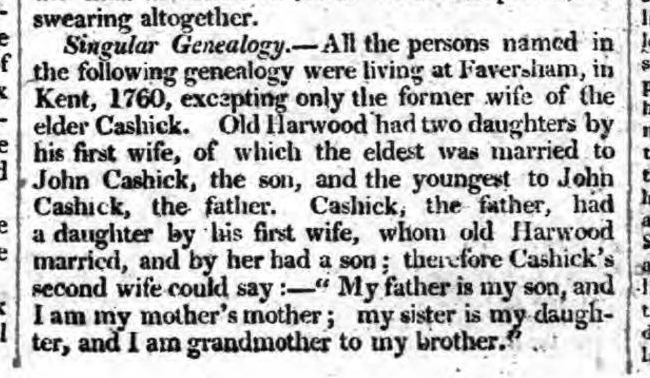

Singular Genealogy. — All the persons named in the following genealogy were living at Faversham, in Kent, 1760, excepting only the former wife of the elder Cashick. Old Harwood had two daughters by his first wife, of which the eldest was married to John Cashick, the son, and the youngest to John Cashick, the father. Cashick, the father, had a daughter by his first wife, whom Old Harwood married, and by her had a son; therefore Cashick’s second wife could say: — “My father is my son, and I am my mother’s mother; my sister is my daughter, and I am grandmother to my brother.”

The article is an excerpt from the Norfolk Chronicle dated Saturday, 3 August 1811. It highlights a peculiar genealogy involving the Harwood and Cashick families in Faversham, Kent, around 1760. Below is a detailed analysis and historical context to help historians and readers understand the relationships and significance of such articles in 1811.

Analysis of the Relationships

The relationships described create a paradoxical and intriguing familial web. Here’s a breakdown:

- Old Harwood’s Family:

- Old Harwood had two daughters with his first wife:

- The eldest daughter married John Cashick, the son.

- The youngest daughter married John Cashick, the father.

- John Cashick, the father:

- John Cashick (father) had a daughter with his first wife. This daughter married Old Harwood and bore him a son.

- Key Result:

- The second wife of John Cashick (father) — Old Harwood’s youngest daughter — made a remarkable genealogical observation:

- “My father is my son”: Because her father-in-law (John Cashick the father) became her stepfather when she married him.

- “I am my mother’s mother”: She became the mother-in-law of her own mother due to the marriage structure.

- “My sister is my daughter”: Her sister became her stepdaughter because of her marriage to her father-in-law.

- “I am grandmother to my brother”: Her brother (via Old Harwood) is simultaneously her grandchild due to her marriage to John Cashick the father.

Historical Context

- Cultural Significance in 1811:

- Articles like this would be seen as amusing and intellectually stimulating for readers. They reflect a fascination with peculiar social structures, genealogical puzzles, and familial relationships that defy typical norms.

- It also underscores how small communities in 18th-century England (like Faversham) could experience intertwined family dynamics due to limited social circles.

- Life in 1811:

- The population often lived in close-knit villages, where marriage alliances were more common within the same community. This sometimes led to complex family connections.

- The storytelling in newspapers catered to the educated middle and upper classes, who would appreciate such intricate familial “oddities” as both entertainment and intellectual challenges.

- Implications for Historians:

- Such articles provide insight into how rural and semi-urban families managed inheritance, property, and marital alliances in the 18th century.

- They reflect not only legal but also social attitudes towards marriage, family structure, and women’s roles within them.

Calculating the Relations

Using modern genealogical terminology:

- Old Harwood’s son (from his marriage to John Cashick the father’s daughter) becomes his grandson-in-law.

- John Cashick the father becomes his son-in-law and also father-in-law to Old Harwood’s eldest daughter.

- The daughter of John Cashick (father’s first marriage) is both stepmother and mother-in-law to Old Harwood’s daughters.

Conclusion

This article serves as a genealogical brainteaser that illustrates the complexities of familial relationships in historical contexts. For modern readers, it offers a glimpse into the humour and intellectual interests of the time, alongside a deeper understanding of 18th-century societal norms and family life.

Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday, 3 August 1811

Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday, 3 August 1811