Reading Mercury – Monday 09 June 1834

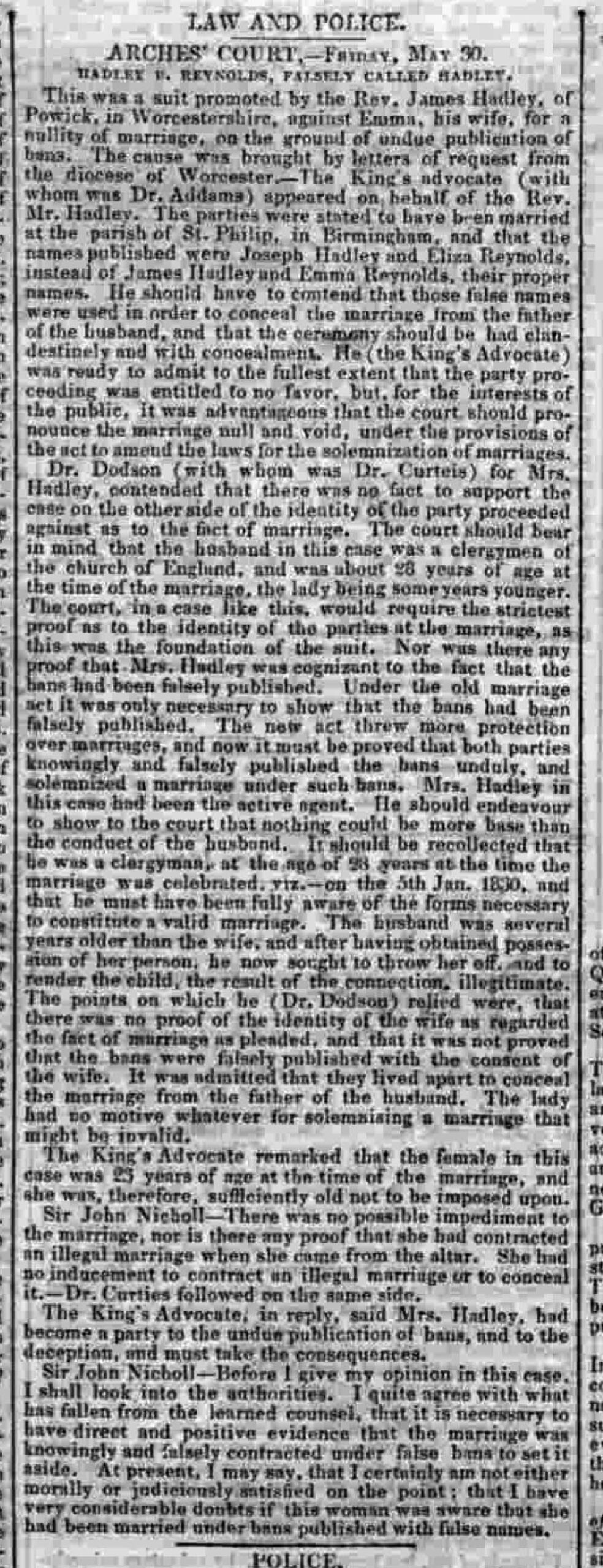

LAW AND POLICE

ARCHES COURT — FRIDAY, MAY 30.

HADLEY v. REYNOLDS, FALSELY CALLED HADLEY.

This was a suit promoted by the Rev. James Hadley, of Powick, in Worcestershire, against Emma, his wife, for a nullity of marriage, on the ground of undue publication of banns. The cause was brought by letters of request from the diocese of Worcester. The king’s advocate (with whom was Dr. Addams) appeared on behalf of the Rev. Mr. Hadley. The parties were stated to have been married at the parish of St. Philip, in Birmingham, and that the names published were Joseph Hadley and Eliza Reynolds, instead of James Hadley and Emma Reynolds, their proper names. He should have to contend that those false names were used in order to conceal the marriage from the father of the husband, and that the ceremony should be had clandestinely to the fullest extent. The king’s advocate proceeded to argue that the husband, as the party promoting the suit, was entitled to no favour, but, for the interests of the public, it was advantageous that the court should pronounce the marriage null and void, under the provisions of the act to amend the laws for the solemnisation of marriages.

Dr. Dodson (with whom was Dr. Curteis) for Mrs. Hadley, contended that there was no fact to support the case on the other side of the identity of the party proceeded against as to the fact of marriage. The court should bear in mind that the husband in this case was a clergyman of the Church of England, and was about 28 years of age at the time of the marriage, the lady being some years younger. The court, in a case like this, would require the strictest proof as to the identity of the parties at the marriage, as this was the foundation of the suit. Nor was there any proof that Mr. Hadley was cognisant of the fact that the banns had been falsely published. Under the old marriage act it was only necessary to show that the banns had been falsely published. The new act threw more protection over marriages, and now it must be proved that both parties knowingly falsely published the banns unduly, and solemnised a marriage under such banns. Mrs. Hadley, in this case, had been the active agent. He should endeavour to show to the court that nothing could be more base than the conduct of the husband. It should be recollected that he was a clergyman at the age of 28 at the time the marriage was celebrated—viz., on the 5th Jan. 1830, and that he must have been fully aware of the forms necessary to constitute a valid marriage. The husband was several years older than the wife, and after having obtained possession of her person, he now sought to throw her off, and to render the child, the result of the connection, illegitimate.

The points on which Dr. Dodson relied were that there was no proof of the identity of the wife as regarded the fact of marriage as pleaded, and that it was not proved that the banns were falsely published with the consent of either. It was admitted that they lived apart to conceal the marriage from the father of the husband. The lady had no motive whatever for solemnising a marriage that might be invalid.

The King’s Advocate remarked that the female in this case was 23 years of age at the time of the marriage, and she was, therefore, sufficiently old not to be imposed upon.

Sir John Nicholl — There was no possible impediment to the marriage, nor is there any proof that she had contracted an illegal marriage when she came from the altar. She had no inducement to contract an illegal marriage or to conceal it.

Dr. Curteis followed on the same side.

The King’s Advocate, in reply, said Mrs. Hadley had become a party to the undue publication of banns, and to the deception, and must take the consequences.

Sir John Nicholl — Before I give my opinion in this case, I shall look into the authorities. I quite agree with what has fallen from the learned counsel, that it is necessary to have direct and positive evidence that the marriage was knowingly and falsely contracted under false names to set it aside. At present, I may say that I certainly am not either morally or judicially satisfied on this point; that I have some considerable doubts if the woman was aware that she had been married under banns published with false names.

Analysis

Key Issues in the Case

- False Publication of Banns: The primary issue was whether the banns (public announcements of an impending marriage) were knowingly and falsely published under false names by either or both parties. This was alleged to conceal the marriage from the husband’s father.

- Consent and Awareness: It was debated whether Emma Reynolds (Mrs. Hadley) was aware of the false publication, and whether she actively participated in the deception. The husband’s role and knowledge of the false banns were also called into question.

- Validity of Marriage: Under the Marriage Act at the time, there were provisions to protect marriages and prevent their nullification on trivial grounds. Proof was needed to establish that the banns were knowingly and falsely published with intent to deceive.

- Motivation: The court scrutinised the motives of both parties, particularly the husband’s. It was implied that he wanted to invalidate the marriage to avoid responsibility for his wife and their child.

Relevant Laws

- Marriage Act of 1823: This Act amended earlier marriage laws, including the requirement that banns or a marriage license must be issued for a valid marriage. It provided stricter provisions against clandestine marriages and required stronger evidence of false declarations to annul a marriage.

- Church of England’s Role: Clergymen were responsible for ensuring proper publication of banns. As Mr. Hadley was a clergyman, his awareness of the rules would be pivotal in assessing whether the marriage was knowingly irregular.

Social Context

- Marriage and Reputation: In 1834, marriage was closely tied to social standing and legitimacy of offspring. A clergyman attempting to invalidate his marriage would face significant social and moral scrutiny, especially given his role in upholding Christian values.

- Women’s Rights: Women had limited agency in legal matters, and allegations of deception or complicity were often hard to refute. The implication that Emma Reynolds acted independently in arranging false banns may have reflected contemporary biases against women.

- Inheritance and Family Dynamics: The effort to conceal the marriage from the husband’s father suggests potential familial conflicts, likely tied to inheritance or status concerns.

Outcome and Implications

- Evidence Required: Sir John Nicholl emphasised the need for direct and positive evidence to annul the marriage. This reflects the increasing rigidity of legal standards under the Marriage Act of 1823.

- Moral Considerations: The court appeared reluctant to annul the marriage without clear proof, partly due to the implications for the child and the reputations of the parties involved.

Reflection on British Life in 1834

- Role of Clergy: As a clergyman, Mr. Hadley embodied a moral and legal authority. His involvement in a potentially irregular marriage would have been scandalous.

- Marriage Laws: The stricter marriage laws of the early 19th century aimed to reduce clandestine and irregular unions, reflecting a societal push for greater order and propriety.

- Gender Norms: Women like Emma Reynolds were often portrayed as either victims or conspirators in legal disputes, with their agency minimised or scrutinised disproportionately.

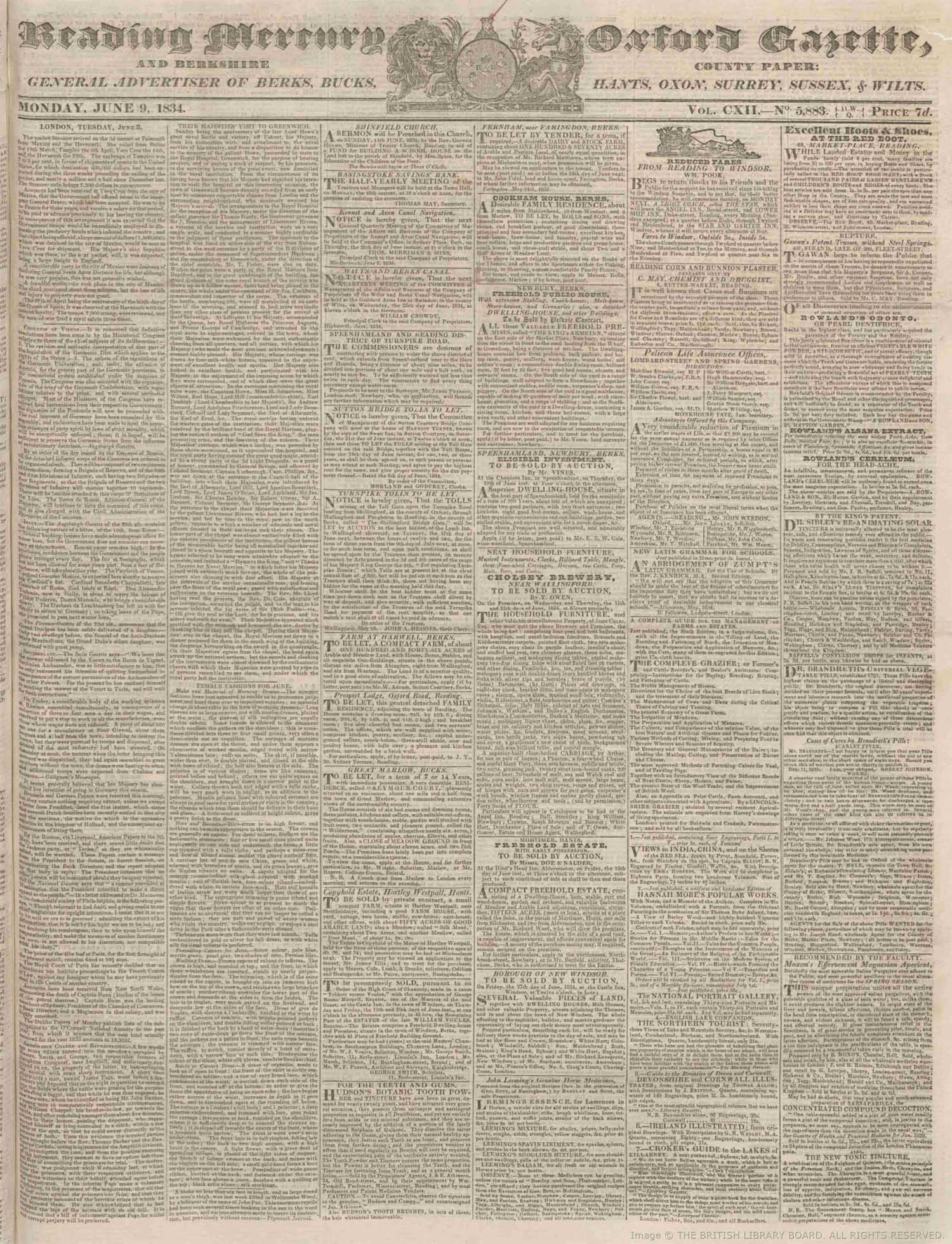

The Reading Mercury

The Reading Mercury holds the distinction of being Reading’s first newspaper, established in 1723. Initially printed by William Carnan, the paper remained under his stewardship until his death in 1737. Following Carnan’s passing, the publication came under the direction of John Newbery (1713–1767), a prominent figure in publishing history. Newbery, who had worked for Carnan, inherited a portion of his estate, married Carnan’s widow, and significantly expanded the reach and influence of the Mercury.

John Newbery’s legacy would later be associated with his pioneering work in children’s literature, but his efforts with the Reading Mercury helped solidify its status as an essential county newspaper. Serving Berkshire as its primary audience, the Mercury also reached into neighbouring counties, including Oxfordshire. In its earliest years, much like other provincial newspapers of the time, it featured minimal local reporting and instead relied heavily on reprinted stories from London’s papers. Despite this, the Mercury established itself as a vital voice for agricultural and commercial communities.

While aligned with the Church of England, the newspaper advocated for religious liberty, reflecting a balanced and progressive stance on key social issues of the day. Over its long history, the Reading Mercury evolved to meet the needs of its readership before finally ceasing publication in 1987, marking the end of an era for one of Berkshire’s most historic newspapers.

Clergyman’s Marriage Scandal: Court Investigates Claims of False Banns in 1830 Union 🚨 #VictorianDrama #MarriageLaw #HistoricalScandal #1834News #ChurchOfEngland