Special report on this page: ‘The Use of Racial and Ethnic Editorial in 1918’

Western Morning News – Friday 05 April 1918

ALLEGED MURDER AT PLYMOUTH.

COLOURED SEAMAN COMMITTED FOR TRIAL.

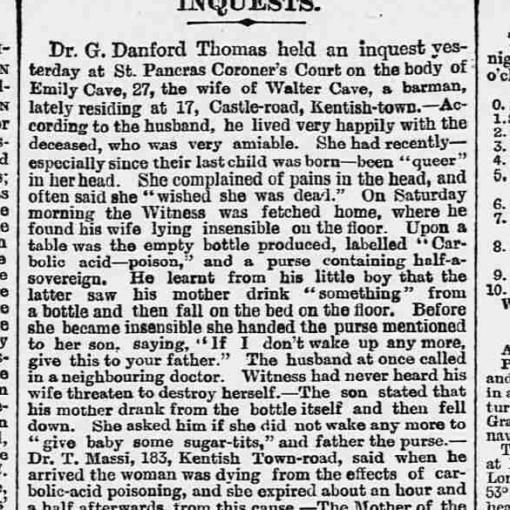

Albert Wilson, Granby-street, a merchant seaman of colour, was charged at Plymouth Guildhall yesterday with the murder of Charles Thomas Padmore, also a coloured man. Mr. Eric Ward prosecuted on behalf of the Director of Public Prosecutions, and Mr. W. H. Sloman defended. — Mr. Ward said on the night of Jan. 12 the two men met in Union-street, when an altercation took place, resulting in the accused striking deceased with a stick. Later accused went to a room in Octagon-street, where deceased lived with a woman named Nellie Gardner. Deceased came back while he was there and ordered him to clear out. Accused went away, secured a stick and was heard to utter threats. At his room he took something from a case and went to deceased’s room again, asked for the deceased to come out, and on his doing so, accused immediately gave deceased “a severe blow on the head” with a stick. As he ran accused continued to strike him, and deceased, having fallen, it is hard to say, “He has stabbed me.” When taken by the police to the Octagon Police Station he had wounds in the arm. At the hospital a knife was found in the stretcher on which deceased was carried, and accused afterwards claimed the knife as his. The knife must have caught in deceased’s clothing and subsequently fallen out.

Accused was subsequently committed for trial for unlawfully wounding, but Padmore subsequently died, the actual cause of death being tuberculosis, but medical evidence was to the effect that he would not have died from that complaint but for the wounds he had received. — Nellie Gardner, who lived with deceased, said, in cross-examination, deceased had been drinking, but was not drunk on the day of the occurrence. — Mrs. Florence White, Hanes Court, Granby-street, said she heard accused say, “I will kill Charlie. He had a stick,” and she said, “Give me the stick, and fight with your fists like a man.” He took something out of a suit case, and P.C. Morgan said accused acknowledged that the knife was what he used for shoemaking. — Dr. Woo, house surgeon at the S. Devon and E. Cornwall Hospital, gave it as his opinion that death, which took place on March 14, was accelerated by the wounds. Deceased refused to take hospital food, and was permitted to have some from outside. He said he had made up his mind to die. — Accused, who reserved his defence, was committed to the Assizes.

Contextualisation and Legal Analysis (1918)

1. The Legal System and Trial Process in 1918

The accused, Albert Wilson, was brought before Plymouth Guildhall for a committal hearing. In the British legal system of the time, magistrates’ courts (like the one at Plymouth Guildhall) did not try serious offences such as murder but instead conducted preliminary hearings to determine whether there was sufficient evidence to proceed to trial at the Assizes.

The Assizes were higher criminal courts in England and Wales, held in major towns and presided over by High Court judges. These courts dealt with the most serious crimes, including murder, manslaughter, and violent assaults.

2. The Charge: Murder vs. Unlawful Wounding

Initially, Wilson was charged with unlawful wounding, a lesser offence under the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, which could carry a prison sentence. However, since the victim, Charles Thomas Padmore, later died, the charge was escalated to murder.

The legal principle of causation was crucial in this case. Although tuberculosis was listed as the cause of death, medical evidence suggested that Padmore’s wounds had significantly contributed to his death. In English law, a person could be held responsible for a death if their actions substantially accelerated it. This followed the legal precedent that “the defendant must take their victim as they find them” (a principle now commonly referred to as the “thin skull rule”).

3. The Role of Race and Social Status

The case involved two coloured men (the historical term used in the article), both described as merchant seamen, which suggests they were part of Plymouth’s maritime workforce. Plymouth, a major naval and commercial port, had a diverse population, including sailors from the Caribbean, West Africa, and other parts of the Empire.

The racial dynamics of early 20th-century Britain meant that Black and mixed-race seamen often faced discrimination both socially and within the justice system. While the article does not explicitly state any bias, it is worth considering that Wilson’s social and racial identity may have influenced both the charge and the trial’s outcome.

4. Evidence and Witness Testimony

Several witnesses testified:

- Nellie Gardner, who lived with the deceased, indicated that Padmore had been drinking but was not drunk.

- Florence White reported that Wilson had made threats to kill Padmore and took something (presumably the knife) from a suitcase.

- P.C. Morgan, a police constable, confirmed that Wilson admitted to owning the knife.

- Dr. Woo, the hospital’s house surgeon, testified that the wounds accelerated death, which was significant in proving causation.

5. Defence Strategy and Trial Implications

Wilson reserved his defence, meaning he did not present a defence at this stage but would do so at the Assizes. This was a common legal strategy in serious cases, often used to avoid self-incrimination before the full trial.

His defence lawyer, W. H. Sloman, might have argued:

- That tuberculosis, not the wounds, was the primary cause of death.

- That Wilson acted in self-defence or under provocation.

- That there was no intent to kill, which could reduce the charge from murder to manslaughter (which carried a lesser sentence).

6. Likely Outcome and Sentencing

In 1918, murder was a capital offence under English law, punishable by hanging. However, if the jury believed Wilson had not intended to kill Padmore but had only intended to cause harm, he could have been convicted of manslaughter, which carried a prison sentence rather than the death penalty.

Judges in the early 20th century had some discretion, but racial bias in sentencing was a concern, as Black defendants often faced harsher penalties than white counterparts.

Conclusion

This case highlights multiple aspects of early 20th-century British law, including murder trials, causation in criminal law, racial and social issues, and the role of Assizes in serious offences. It provides a window into how justice operated in wartime Britain, particularly for marginalised communities such as Black seafarers.

The History of The Western Morning News

Founding and Early Years (1860s–1890s)

The Western Morning News was established in 1860 in Plymouth, Devon, as a daily newspaper serving the West Country. It was founded by Edward Spender and William Saunders, both ambitious journalists who saw an opportunity to provide a high-quality regional newspaper covering the counties of Devon and Cornwall.

Edward Spender, a journalist from Bath, had strong editorial principles and a vision for an independent and informative newspaper. His co-founder, William Saunders, was also a newspaper proprietor and later became a Liberal MP. Together, they sought to produce a publication that would bring national and international news to the rural areas of the West of England, offering readers well-researched reporting at a time when local newspapers often relied on hearsay and second-hand reports.

The paper quickly gained a reputation for its serious journalism, in-depth reporting, and independent editorial stance, distinguishing itself from other provincial newspapers, which often had strong political affiliations.

Expansion and Influence (Late 19th Century – Early 20th Century)

By the late 19th century, The Western Morning News had become one of the leading regional newspapers in the country. It expanded its coverage to include more than just news, featuring reports on agriculture, shipping, mining, and rural affairs, which were vital to the economy of Devon, Cornwall, Somerset, and Dorset.

Its editorial policies often aligned with Liberal politics, but the newspaper maintained an independent voice, frequently challenging both Conservative and Liberal governments when necessary. It took a progressive stance on many issues of the time, including education reform and social justice.

The newspaper was also known for its coverage of maritime affairs, reflecting Plymouth’s importance as a naval and commercial port. Shipping movements, wrecks, and fishing industry reports were regular features, making it a must-read for the seafaring community.

The First and Second World Wars (1914–1945)

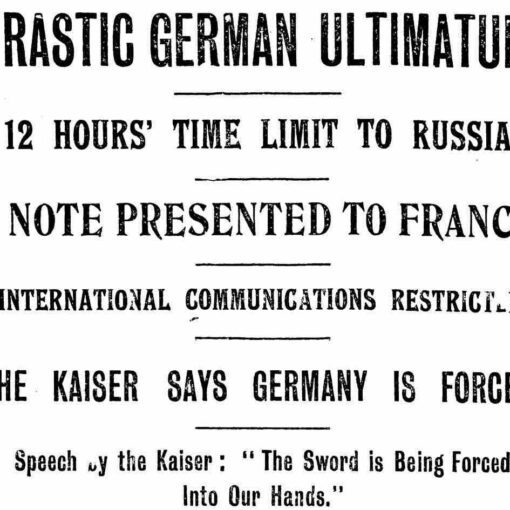

During the First World War (1914–1918), The Western Morning News played an important role in reporting on the war effort from a West Country perspective. It covered local enlistments, battles, war casualties, and home-front struggles. The newspaper also ran propaganda pieces in support of the war, encouraging local men to enlist and reporting on fundraising efforts for the troops.

By the Second World War (1939–1945), Plymouth had become a major target for German air raids, particularly during the Blitz of Plymouth in 1941, which devastated much of the city, including the newspaper’s offices. Despite this, The Western Morning News continued publication, providing vital information to local residents and wartime authorities.

Post-War Period and Modernisation (1945–1980s)

After the war, the paper modernised, adopting new printing technologies and increasing its coverage of national and international news. During the 1950s and 1960s, it remained a key source of information for the West Country, covering political changes, economic shifts, and social issues affecting the region.

During this period, the paper maintained a focus on regional interests, including:

- Tourism in Devon and Cornwall, which grew significantly in the post-war years.

- The decline of traditional industries such as mining, fishing, and shipbuilding.

- The rise of environmental awareness, particularly concerning coastal conservation.

By the 1980s, the paper had further expanded its readership, appealing to a broader audience while maintaining a focus on local stories.

Ownership Changes and Consolidation (1990s–2000s)

Like many regional newspapers, The Western Morning News saw major changes in the 1990s and 2000s, with shifts in ownership and technological advancements.

- In 1997, the paper was acquired by Northcliffe Newspapers Group, a subsidiary of Daily Mail and General Trust (DMGT).

- Under Northcliffe’s ownership, the paper underwent significant restructuring, including investments in digital technologies and an improved printing process.

- In 2012, ownership changed again when the newspaper became part of Local World, a company that brought together several regional newspapers.

- In 2015, The Western Morning News became part of Reach plc (formerly Trinity Mirror), one of the UK’s largest newspaper groups.

During this period, the paper faced challenges from the rise of the internet, declining print circulation, and changing reader habits. To adapt, it launched an online edition, increasing its digital presence while maintaining its print edition.

The Present Day (2010s–2020s)

Today, The Western Morning News continues to serve Devon, Cornwall, and the wider West Country region, though its readership is smaller than in its peak years. It remains an important source of local news, business reports, and sports coverage, particularly for agriculture, tourism, and regional politics.

The newspaper has adapted to the digital age, with a strong online presence through the website DevonLive and CornwallLive, which provide breaking news, live updates, and investigative journalism.

Legacy and Importance

Despite the decline of print media, The Western Morning News has remained one of the most respected regional newspapers in England. Its commitment to local journalism, historical reporting, and regional identity has ensured its survival for over 160 years.

It is one of the few British newspapers that can trace its history back to the Victorian era and still be published today. Its archives provide an invaluable historical record of life, politics, and culture in the West Country, making it an essential resource for historians, genealogists, and researchers.

Plymouth Murder Trial: Coloured Seaman Accused of Fatal Attack

#PlymouthHistory #CrimeHistory #1918 #BritishJustice #MurderTrial #WestCountryHistory #LegalHistory #HistoricalNewspapers #TrueCrime #ColonialBritain #MerchantSeamen