Introduction: The British Media and Racial Narratives – From the Press to the Digital Age

This imagined 18th-century oil painting captures the racial attitudes of Georgian Britain with harrowing clarity. A solemn African man, bound by a heavy iron chain, sits silently under the gaze of three white British men. Their expressions range from patronising curiosity to cold superiority, reflecting the period’s prevailing ideology of racial hierarchy. The composition evokes a scene not of justice, but of rationalised oppression—framed as civilised debate. Rendered in rich, muted tones, the artwork underscores how intellectualism and empire coexisted with brutal dehumanisation, capturing a moment steeped in moral contradiction and racialised power.

The British press has long held a pivotal role in shaping public perceptions of race, ethnicity and national identity. From the Georgian era to the post-war period, newspapers mirrored—and often reinforced—the racial ideologies of their time. Whether justifying imperial conquest or sensationalising perceived threats, the press consistently acted as both a reflector and shaper of Britain’s evolving relationship with race.

In the post-1950 era, however, this influence extended beyond print. The rise of radio, television and—more recently—the internet and social media has transformed how racial narratives are framed, challenged and disseminated. This extended study examines how traditional British newspapers, followed by broadcast and online media, have contributed to the construction, reinforcement and at times, the deconstruction of racial hierarchies from the 18th century to the 21st.

1. The Georgian Era (1714–1837): Empire, Exploitation and the Beginnings of a National Press

In the Georgian period, Britain’s imperial project intensified. The press, while still relatively elite and London-centric, began to take shape as a national force. Newspapers such as The Morning Chronicle, The Times and The Morning Post presented content steeped in colonial assumptions.

1.1 Language of Empire

Africans, Caribbeans and Indigenous peoples were typically portrayed in dehumanising and objectifying terms—described as “heathens,” “savage,” or “childlike.” The enslaved were referred to not as individuals, but as labouring assets.

Colonial violence and expansion were justified through paternalistic narratives about “civilising missions.” Indigenous resistance—whether in the Americas, Africa, or Australia—was almost universally framed as irrational or barbaric.

1.2 Dissenting Voices

This imagined Victorian oil painting captures the stark visual language of racial and class prejudice in 19th-century Britain. Set in a backstreet slum of brick and shadow, an Irish man sits barefoot and weary, while beside him stands a solemn Indian figure, draped in traditional garb. Opposite them, two well-dressed Englishmen—an older gentleman with a cane and a younger man in a bowler—regard the pair with a mixture of pity, suspicion and quiet contempt.

Their body language speaks volumes: the power to judge without understanding, to define without being defined. The painting draws on Victorian moral codes and imperial assumptions, revealing how poverty, race and perceived worth were deeply entangled in Britain’s social imagination. This work echoes the silent cruelty of a system that presumed superiority while masking it as civility.

While abolitionist perspectives emerged, most notably through The Anti-Slavery Reporter (1825–), mainstream newspapers were overwhelmingly hostile or indifferent to the anti-slavery cause until public opinion shifted in the early 19th century. Even then, racial hierarchies remained intact within abolitionist rhetoric, which often framed Black people as victims to be pitied rather than equals.

2. The Victorian Era (1837–1901): Industrial Expansion and the Rise of Racial Stereotyping

Victorian Britain saw a massive expansion in newspaper circulation, driven by urbanisation, literacy and technological advancement. With an empire that spanned the globe, the press became a powerful tool for normalising white supremacy.

2.1 The Inferior ‘Other’

Colonial subjects were depicted as primitive and dependent. India, particularly after the 1857 Rebellion, became a focal point for alarmist and racist coverage, framing Indians as duplicitous and violent.

The Irish were often caricatured as brutish or lazy in coverage of the Great Famine—an ethnicised form of reporting that blurred into racial stereotyping. Black and Asian figures were cast either as exotic novelties or dangerous criminals.

2.2 Crime, Panic and the ‘Black Peril’

The trope of the ‘Black Peril’—the alleged sexual threat of Black men to white women—first emerged in this era. Newspapers sensationalised such fears, reinforcing pseudo-scientific notions of racial danger. These narratives often appeared in provincial papers as well as London dailies.

3. The Edwardian Period (1901–1910): Immigration Fears and the Roots of Modern Racism

The Edwardian press amplified fears about Britain’s changing racial and ethnic make-up. Migration, particularly of Jewish and Chinese populations, was portrayed as an existential threat.

3.1 The ‘Alien Problem’

The rise of anti-Semitic sentiment was encouraged by mass-market papers like The Daily Mail and The Daily Express, which depicted Jewish migrants as parasitic, deceitful and culturally alien. This culminated in public support for the Aliens Act 1905—the first modern immigration restriction in Britain.

Chinese communities were vilified through lurid stories linking them to crime, opium use and the so-called ‘Yellow Peril’—a racialised fear of East Asian influence and masculinity.

3.2 Colonial Troops and Racial Hierarchies

The Boer War prompted debate about colonial military support. While colonial troops were acknowledged, they were rarely humanised. Black South Africans, in particular, were depicted as inferior both morally and militarily.

4. The World Wars (1914–1945): Sacrifice and Selective Inclusion

Britain’s reliance on colonial troops during both World Wars complicated but did not dismantle racial prejudices in the media.

4.1 World War I: Visibility Without Equality

This imagined oil painting captures the racial dynamics of World War I through a composition both honouring and critiquing. A group of soldiers stands amid the smoke and rubble of the Western Front. At the centre, a white British officer rises prominently, bathed in light, his posture firm and resolute. Surrounding him are African, Caribbean and Indian troops—visibly present yet visually subordinated.

While African, Caribbean and Indian soldiers were sometimes praised for loyalty, they were rarely afforded the same honour or agency as their white counterparts. British newspapers largely focused on white heroism while relegating colonial soldiers to supporting roles.

Negative press coverage of Black and Asian communities in post-war Britain helped fuel the 1919 race riots, often portraying migrants as violent or sexually aggressive.

4.2 World War II: Anti-Fascism and Hypocrisy

The British press used anti-Nazi rhetoric to promote imperial unity but failed to confront Britain’s own racial double standards. Reports on American segregation were critical, but British colonial racism remained unexamined.

Jewish refugees escaping Nazi persecution received uneven coverage—sympathy mingled with anti-Semitic stereotypes about foreignness, control and economic threat.

5. 1945–2000: From Windrush to Multicultural Britain

Post-war Britain saw a dramatic transformation in racial discourse. The arrival of Commonwealth migrants, beginning with the Empire Windrush in 1948, triggered both welcome and hostility in the press.

5.1 Early Responses

Left-leaning newspapers like The Guardian and The Observer cautiously welcomed immigration, highlighting labour shortages and integration efforts. However, this was not the norm.

The Daily Mail and The Daily Express led with alarmist coverage, warning of ‘invasion’, ‘ghettos’ and ‘cultural decay’. This helped shape enduring narratives of racial otherness, particularly during moments of national anxiety such as economic recessions or urban unrest.

5.2 Crime, Riots and Representation

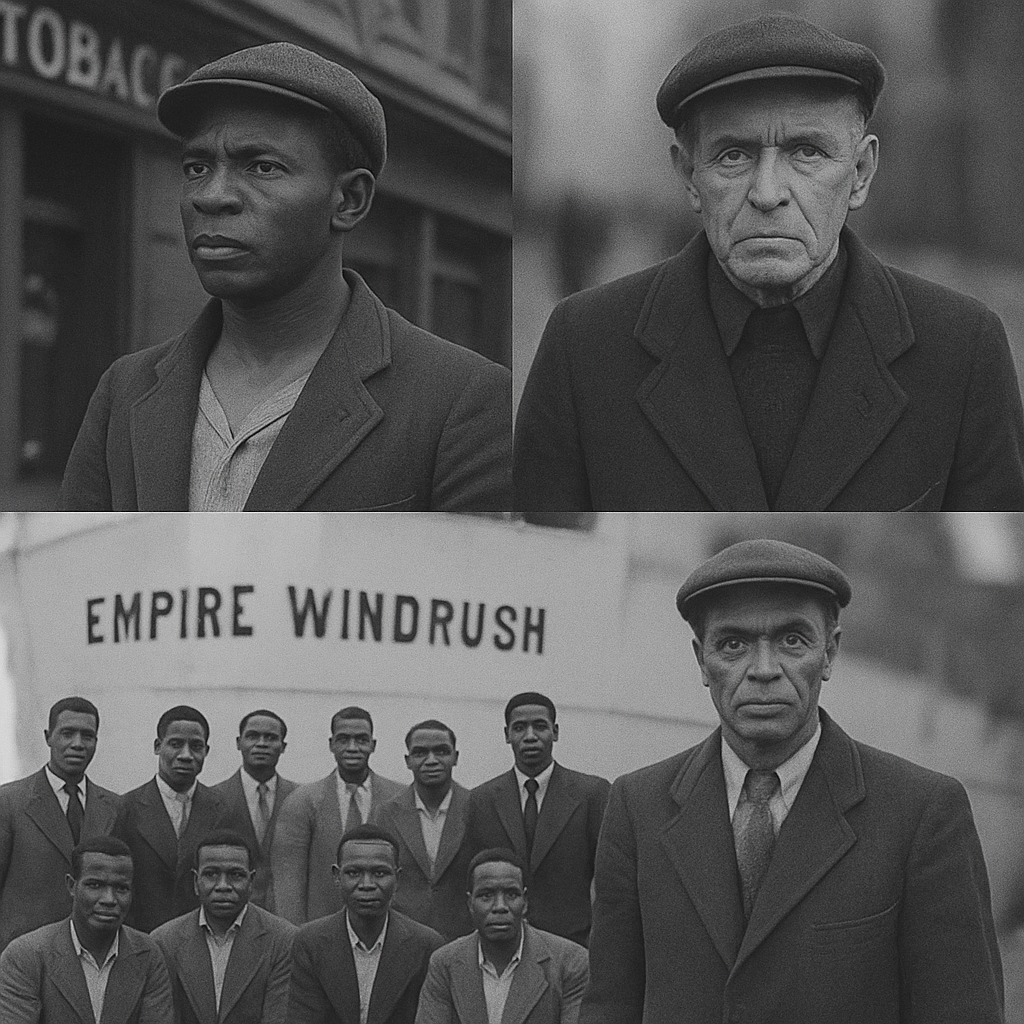

This black-and-white photographic collage evokes the complex emotional landscape of post-war Britain through a study in stillness and expression. In the lower half, a group of sharply dressed Caribbean men stand beside the SS Empire Windrush, embodying dignity, hope and the promise of rebuilding a battered nation. Above, a pair of British men—older, weathered and silent—stare directly into the lens with furrowed brows and unreadable gazes.

Though no words are spoken, the contrast between figures speaks volumes. This image captures a pivotal historical tension: the optimism of arrival met by a society uncertain of change. Without placards, slogans, or confrontation, it offers a quiet but profound meditation on race, identity and the cultural reckoning that Britain faced—and continues to face—in the wake of empire.

Coverage of the 1958 Notting Hill riots, the 1981 Brixton riots and the 1993 murder of Stephen Lawrence revealed deeply embedded racial biases. The press often criminalised entire communities in the wake of unrest.

Even when covering victims of racism, the media frequently sanitised or deflected attention away from institutional failures. In the 1990s, tabloid stories about asylum seekers and Muslims began to replace older tropes about Caribbean migrants, suggesting a shifting but persistent racial anxiety.

6. 2000–Present: Digital Media, Social Movements and Racial Reckonings

The 21st century brought seismic shifts in how race is discussed and debated in the British media landscape.

6.1 The Legacy of the Press

Many of the narratives established by centuries of biased print journalism persist today. Dog-whistle headlines in tabloid media continue to frame migrants, Muslims and Black Britons through a lens of suspicion.

Outlets such as The Sun and The Mail Online have faced criticism for fuelling anti-immigrant sentiment through selective reporting and inflammatory language. Even mainstream broadcasters have often been slow to reflect Britain’s diversity in staffing or output.

6.2 Broadcast Media and New Voices

The BBC has been both praised for inclusive programming and criticised for its treatment of racial issues, particularly in its political coverage and hiring practices.

Channel 4 has played a more progressive role in showcasing multicultural Britain, while Sky News and ITV have taken varied approaches depending on leadership and editorial direction.

Digital platforms have offered counter-narratives. Independent voices on YouTube, podcasts, blogs and social media have allowed underrepresented communities to challenge mainstream racial framings. Movements such as Black Lives Matter UK and campaigns against the government’s ‘hostile environment’ immigration policies have received widespread online support—even when traditional media have been slower to respond.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy and Shifting Frontiers of British Racial Media Narratives

From imperial propaganda in Georgian newspapers to algorithmically driven online racism, the British media has long played a formative role in shaping the nation’s ideas about race, belonging and difference.

While efforts at inclusion and accountability have grown in recent decades—particularly following watershed moments such as the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry and the Windrush scandal—the structures established over centuries of racialised reporting remain deeply embedded.

The future of British media, across print, broadcast and digital platforms, depends not only on recognising these patterns but on actively dismantling them. Only by doing so can a more honest, inclusive and representative public discourse begin to take shape.