Before Mr. Preston, at the Borough Police Court, on Wednesday, four young seamen, named John Mullin, 4, Byrom-street; James Allsop, 140, Beckwith-street; Gardner Carruthers, 280, Conway-street; and William Lewis Seacombe, were charged with stealing a sailor’s white canvas bag from Birkenhead Railway Station, on the night of the 6th inst. The bag contained wearing apparel and other articles, valued at £5, and was the property of John Anderson, a seaman.

Mr. Preston, jun., conducted the prosecution. From his opening statement, it appeared that the prisoners and Anderson had all been employed together on the s.s. Castleford. They left the ship together on the 6th inst. by the London and North Western train. Prisoners got out at Birkenhead, and Anderson left for Liverpool. The prisoners had taken the bag, which was missed by the owner, and information was given to the railway officials, by whose detective (Richards) the bag and its contents were traced to the prisoners.

John Anderson, a seaman residing at 117, Wellington-road, Liverpool, said that on the 6th inst. he was a passenger from Swansea to Liverpool, and had a bag and his things in it. The four prisoners were travelling in the same carriage on the London and North Western Railway, but were going to Birkenhead, and they got out at Whitchurch to change for that place. When he arrived at Lime-street Station his bag could not be found, and he gave information to the railway authorities. Yesterday he met Mullins, who was wearing his (witness’s) trousers. The bag was afterwards found, and he identified the things produced. It was found in the house in which the prisoner Lewis resided at 24, Hawthorn-road, Seacombe, where witness was taken by Detective Richards.

Samuel Lewis, fireman, brother of the prisoner Lewis, stated that he saw the four others travelling on the 6th inst. On arriving at Whitchurch they changed trains for Birkenhead, the prosecutor remaining in the train for Liverpool. Allsop held Anderson’s bag between his other legs, and the bags were taken to the train for Birkenhead. On arriving at Birkenhead they were brought together at the Cuckoo Hotel, where Anderson’s bag was opened, and Allsop and Carruthers pulled the clothes out, saying: “Let us have a dive.” Witness’s brother then pulled out some of the things, and ultimately they were divided among them, and his brother got the bag.

John McManus, residing at 47, Claughton-road, Birkenhead, said he was one of the seamen travelling, and corroborated the evidence of the last witness. Mullin had no bag of his own, and he carried William Lewis’s bag, while William Lewis carried the stolen bag.

Detective Bateman gave evidence that about half-past one on Tuesday Railway Inspector Richards came to the Birkenhead Police-station with Mullin, stating that a bag belonging to a man named Anderson had been stolen from the station at Whitchurch. Witness went to search Mullin’s house. He there found the small bag containing tobacco, which had been identified by Anderson as his. He also searched Allsop’s house, 140, Beckwith-street, and found the oilskin coat produced. He then came back to the booking-office and asked Mullin how he could account for the coat, and also for the small bag. He said, “Lewis gave me the coat.” Witness then asked him where Lewis was, and he replied, “I should be better able to tell you than me.” Witness met Allsop at the Ferry, but he denied all knowledge of the bag. He asked Allsop how he could account for an oilskin coat found in his house. He said, “It is my oilskin.” Witness then went to Seacombe and apprehended Lewis in the Bird Inn. When accused of participation in the theft he said, “I know nothing at all about it.” Witness then took prisoner to his mother’s house, telling him on the way that Allsop, Mullin and Lewis were locked up. He said, “I will tell the truth.” He hung down his head for a little and afterwards sent his sister to a house where he had been staying, and she brought the bag which then contained a number of articles of wearing apparel. He then stated that Allsop had given him the bag. Carruthers was apprehended in the street. He said, “I know nothing about the bag.”

The prisoners at first pleaded not guilty, but were informed by the Stipendiary that they would have to be sent to the sessions unless they pleaded guilty.

Mullin said, “Well, I will plead guilty, but I know nothing about it.”

The others pleaded guilty unconditionally, and were each sent to hard labour for three months.

Table of Contents

ToggleTravelling by Railway in the 1800’s

1. Robberies and Theft

- Incidents of theft were common, as railway travel often brought together people of diverse backgrounds in confined spaces. Thieves, pickpockets, and opportunists targeted passengers, particularly those carrying luggage or valuables.

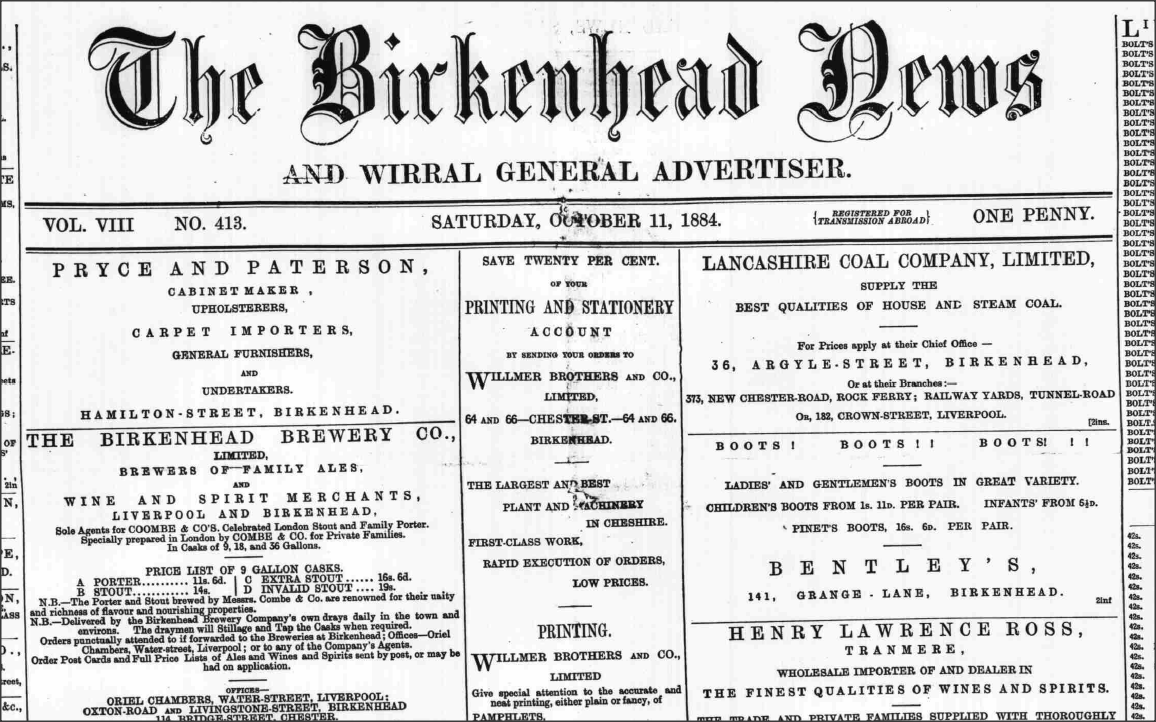

- The case from the Birkenhead News (1884) highlights the risk of luggage theft, where four sailors stole a fellow passenger’s bag, containing clothes and personal items. Theft could occur at stations, on the trains, or even during stopovers at hotels near the railways.

- Lack of secure luggage systems: Luggage was often stored in overhead racks or separate compartments, making it easier for thieves to steal without detection.

2. Physical Attacks and Assaults

- Highwaymen and bandits: In rural or isolated areas, trains were occasionally ambushed by bandits. Passengers were sometimes held up at gunpoint, though this was less common compared to stagecoach robberies.

- On-board violence: Railway cars brought strangers into close quarters, and disputes could turn violent. Drunken brawls and physical altercations between passengers were a frequent concern, especially on long-distance journeys.

- Vulnerability to conmen: Some passengers fell victim to fraudsters or swindlers who preyed on the less experienced or more trusting travellers.

3. Risks for Women Travelling Alone

- Social stigma and fears: Women travelling alone were viewed with suspicion or concern in the Victorian period. It was often considered improper for a woman to travel unaccompanied, and this social expectation added to their vulnerability.

- Sexual harassment and assault: Women were at particular risk of harassment or assault, especially in carriages where they might find themselves alone with male passengers. There were reports of inappropriate behaviour by both fellow travellers and railway staff.

- Separate compartments introduced: To address these concerns, railway companies eventually introduced ladies-only compartments in the mid-19th century, though these were not universally available.

- Travel anxiety: Many women were hesitant to travel alone due to societal fears about safety and propriety, which were amplified by sensationalist press reports of attacks or thefts targeting female passengers.

4. Accidents and Railway Safety

- Derailments and collisions: The early railways were prone to accidents due to poorly maintained tracks, rudimentary signalling systems, and inexperienced operators. Derailments, head-on collisions, and boiler explosions were relatively frequent and often fatal.

- Injuries during boarding or alighting: Open carriages and platforms posed risks, particularly for elderly passengers, women in heavy skirts, or children. Falling while entering or exiting a moving train was a significant danger.

- Lack of safety measures: Early trains lacked the safety features we take for granted today, such as automatic brakes, safety glass, or clear emergency exits.

5. Station and Platform Risks

- Crowding and pushing: Platforms at major stations could become dangerously overcrowded, particularly during peak travel times or when multiple trains arrived simultaneously.

- Pickpockets and swindlers: Stations were hotspots for crime, as passengers were often distracted while navigating timetables, purchasing tickets, or managing their luggage.

- Lighting and visibility: In rural areas or at night, poorly lit stations made travellers more vulnerable to attacks or theft.

6. Anxiety and Social Paranoia

- The novelty of train travel created psychological unease for some passengers. The rapid speed of early trains (unprecedented at the time) led to concerns about “railway madness,” where it was feared that prolonged exposure to train travel might cause mental breakdowns.

- Sensationalist media often exaggerated incidents of violence or theft on trains, creating a heightened fear of railway travel, especially among the middle and upper classes.

Historical Responses to These Dangers

- Introduction of police forces: Many railway companies began employing their own police (e.g., the Railway Police in Britain) to patrol stations and trains, reducing incidents of theft and violence.

- Segregated carriages: Ladies-only compartments were introduced to protect women travelling alone, though they were not always effective in preventing harassment.

- Improved signalling systems: Advances in railway technology and stricter government regulations led to safer trains and fewer accidents.

- Public awareness campaigns: Newspapers and pamphlets often advised passengers on how to protect themselves, such as staying vigilant about their belongings and avoiding travelling alone late at night.

While railway travel in the 19th century was a marvel of industrial progress, it came with significant risks, especially for those travelling alone or carrying valuables. Robberies, accidents, and harassment were serious concerns, but over time, improvements in technology, law enforcement, and societal awareness helped mitigate many of these dangers. Articles like the one from the Birkenhead News provide invaluable insights into the lived experiences of railway passengers and the evolving challenges of Victorian travel.

Analysis of Historical Usefulness

This article is highly useful for historians, particularly those researching Victorian crime, law enforcement, and transportation networks:

- Social Context: It provides insight into the lives of sailors, their interactions, and how they travelled during the late 19th century, reflecting the reliance on trains as a major mode of transportation.

- Law and Order: The article details the legal procedures, such as the role of railway inspectors, detectives, and the court system in handling theft. It also highlights attitudes towards petty crime and punishment (e.g., sentencing to hard labour).

- Economic Detail: The stolen goods were valued at £5, giving historians an idea of the perceived value of possessions in this period.

- Railway History: It illustrates how railways functioned, including connections between stations and how they were policed, shedding light on the logistics and infrastructure of the era.

- Community and Class: The mention of various streets and hotels adds to the understanding of the geographic and social makeup of Birkenhead and Liverpool during this period.

- Legal Records: The handling of confessions and how guilt was determined is indicative of Victorian legal practices, which often pressured suspects into confessions.

For researchers focusing on local history, this article also offers a snapshot of Birkenhead in 1884, including specific locations like the “Cuckoo Hotel” and details about residents.

Free to use British Newspaper Research Service

British newspapers offer a treasure trove of information for family historians. They capture moments in time, providing context, character, and community insight that official records cannot. With the free service provided by Old British News, this research becomes even more accessible, enabling historians to delve into rich, untold stories of their relatives. By combining these resources with other records, family historians can create a more complete and engaging picture of the past.

I search historical articles to locate mentions of your ancestors—whether they were involved in notable events or simply part of the everyday life reported in these newspapers. If relevant articles are found, I deliver them to you in a PDF format at no cost.

If I find articles, they’ll be sent to you in a clear, organized PDF. If not, you’ll be informed right away. See here.