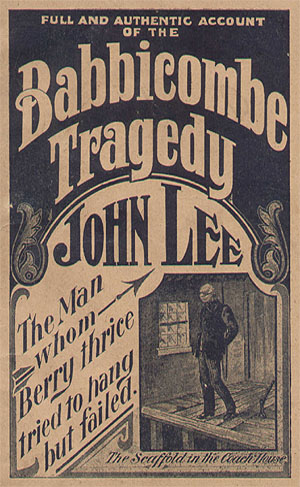

The astonishing story of John “Babbacombe” Lee, the man they could not hang who defied death after surviving three failed execution attempts.

Synopsis

John Lee, a twenty-year-old Devonshire lad, worked as a footman and gardener for Miss Emma Keyse, an elderly spinster, at her home, The Glen, situated on Babbacombe Bay near Torquay. On 15th November 1884, Miss Keyse was discovered murdered—her skull was shattered, her throat slashed from ear to ear, and her body set alight amidst five deliberately set fires within the house.

John Lee, a twenty-year-old Devonshire lad, worked as a footman and gardener for Miss Emma Keyse, an elderly spinster, at her home, The Glen, situated on Babbacombe Bay near Torquay. On 15th November 1884, Miss Keyse was discovered murdered—her skull was shattered, her throat slashed from ear to ear, and her body set alight amidst five deliberately set fires within the house.

Circumstantial evidence pointed towards Lee’s involvement, leading to his arrest and charge for both murder and arson. Despite maintaining his innocence, Lee was unconvincing in his defence, telling untruths that hindered police efforts to uncover the true culprit. The prosecution suggested that Lee’s motive stemmed from anger over a recent cut to his already paltry wages. He was convicted and sentenced to death. Remarkably, as the sentence was delivered, Lee calmly declared, “I am so calm because I trust in my Lord, and He knows that I am innocent.”

On 23rd February 1885, Lee was led to the gallows to be hanged. However, the execution apparatus failed three times in front of witnesses, a macabre spectacle that captured national attention. Each time the lever was pulled, the trapdoor refused to open. When tested without Lee, the mechanism worked perfectly. Following this bizarre event, the Home Secretary commuted Lee’s sentence to life imprisonment. Lee claimed divine intervention had spared him, reinforcing public doubts about his guilt and earning him the legendary title of “The Man They Could Not Hang.”

After spending 22 years in prison, Lee was released in 1907. He later made a living by exploiting his notoriety, giving talks about his experiences. He married and had two children but abandoned his family around 1911, emigrating thereafter. His later years remain a mystery, with conflicting reports placing him in the United States, Canada, and Australia.

In 1936, a peculiar article appeared in Torquay’s Herald and Express. It claimed The Man They Could Not Hang had revealed the true events of the night Miss Keyse was killed. According to the article, Lee allegedly admitted he was not the murderer but had attempted to shield a friend involved in the crime. This account implicated a man of high public standing, who, in a fit of anger during a party, killed Miss Keyse. Lee, it was said, had tried to cover up the crime, unwittingly implicating himself.

The 1884 Backdrop

By 1884, Torquay was a flourishing coastal town, regarded as one of England’s most desirable watering places. It boasted a population of nearly 25,000 and vied with Scarborough for the title of “Queen of English Watering Places.” The town was renowned for its picturesque scenery, with white limestone houses nestled amongst lush foliage, overlooking the natural bay. A favourite destination for both tourists and convalescents, Torquay retained an aristocratic charm.

The nearby villages of St. Marychurch and Babbacombe had become suburbs of Torquay by this time. St. Marychurch, located half a mile northwest of Babbacombe, was a leafy, hilly area centred around its parish church. Babbacombe, two miles from Torquay along the coast, was an idyllic bay surrounded by quaint villas and cottages. Its shingle beach and wooden jetty were frequented by sturdy fishermen and curious tourists alike, many of whom sought refreshments at the rustic Cary Arms or chartered fishing boats for leisure trips.

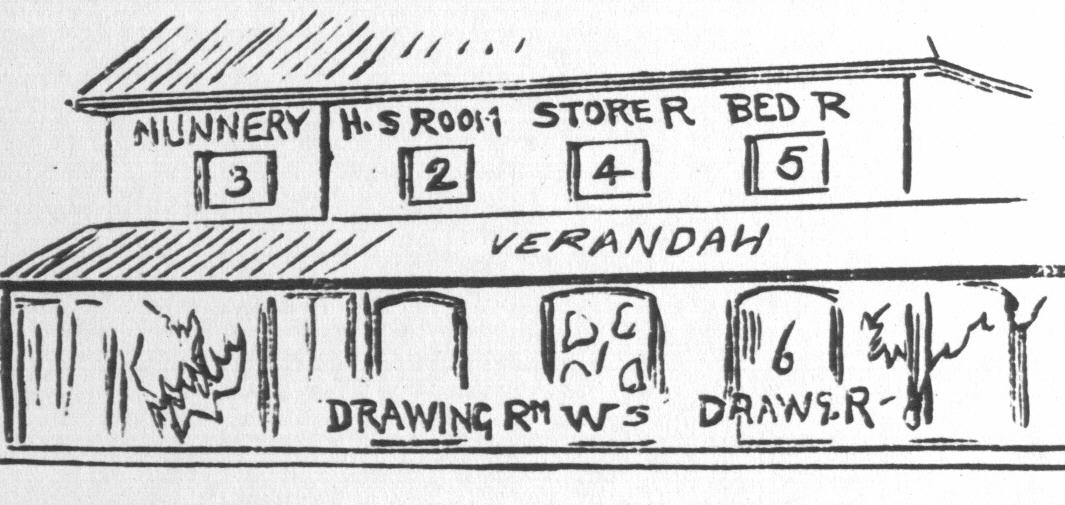

Miss Keyse’s residence, The Glen, stood almost level with the beach, commanding a striking view of the sea. The long, two-storey thatched building, separated from the beach by a low fence and wall, was described as a charming summer retreat. However, during the bleak winter months, it could appear dreary and desolate, particularly on the tragic November day of her death, with the trees bare, an east wind howling, and heavy surf crashing against the shore.

The property was surrounded by a wooded plantation, crisscrossed with meandering paths leading to secluded spots offering spectacular coastal views, including the renowned Babbacombe Bay. The estate also featured well-maintained lawns, gardens, and croquet or tennis facilities. Inside, the house had a lofty hall, drawing and dining rooms, a breakfast room, nine bedrooms, and various service quarters.

At the time of the tragedy, The Glen was home to Miss Keyse, her two elderly maids, Jane and Eliza Neck, the cook Elizabeth Harris (Lee’s half-sister), and John Lee, who worked as both footman and gardener.

Knee Deep in Blood

On 28th October 1884, Miss Emma Keyse finalised the sale of The Glen for £13,000, having tried to sell the property for months. That same day, she informed her cook, Elizabeth Harris, and John Lee about their future employment. Harris later testified that she had been “settled up” with, though it remains unclear whether this meant she was dismissed or simply paid her quarterly wages. Lee, on the other hand, was told his wages would be reduced from two shillings and sixpence a week to just two shillings. For Lee, who had earned three shillings a week at the age of fifteen and who compared his earnings to the thirteen shillings a week farm labourers made, the reduction was a bitter blow. Miss Keyse also mentioned that his employment was uncertain but promised to help him find another position, possibly with the new owner.

On 28th October 1884, Miss Emma Keyse finalised the sale of The Glen for £13,000, having tried to sell the property for months. That same day, she informed her cook, Elizabeth Harris, and John Lee about their future employment. Harris later testified that she had been “settled up” with, though it remains unclear whether this meant she was dismissed or simply paid her quarterly wages. Lee, on the other hand, was told his wages would be reduced from two shillings and sixpence a week to just two shillings. For Lee, who had earned three shillings a week at the age of fifteen and who compared his earnings to the thirteen shillings a week farm labourers made, the reduction was a bitter blow. Miss Keyse also mentioned that his employment was uncertain but promised to help him find another position, possibly with the new owner.

Witnesses recalled Lee’s reaction that day. Elizabeth Harris stated, “John came into the kitchen crying… and said Miss Keyse was going to pay him two shillings a week.” Jane Neck reported that Lee felt disappointed and angry, saying, “I will not stop another night… before I leave Torquay, I will have my revenge.” William Richards, a local postman, corroborated this, noting that Lee had confided about a row with his mistress and had threatened to leave her service.

In the days leading up to the murder, Lee wrote a letter to his sweetheart, Kate Farmer, suggesting they end their engagement. He mentioned feeling “unsettled” and tired of his work, hinting that he intended to seek a new direction in life. Kate, however, responded with a heartfelt plea, refusing to let him break off their relationship.

The Night Before the Murder

On Friday, 14th November 1884, Elizabeth Harris noted that she last saw Miss Keyse at prayers after breakfast. Feeling unwell, Miss Keyse retired to her room at 5pm. Harris also felt ill that evening, which was later speculated to be early symptoms of pregnancy. In her autobiography, Harris recounted Lee offering to fetch a doctor for her, but she declined.

That night, prayers were held at 11pm, attended by Harris, Jane Neck, and John Lee. Afterwards, Lee retired to the pantry where he slept, while the others went to their respective rooms. Jane and Eliza Neck, who shared a room, noted that everything appeared normal as they went to bed. Miss Keyse was last seen in her dining room, writing in her journal.

The Morning of the Fire

In the early hours of 15th November 1884, smoke filled The Glen. Elizabeth Harris raised the alarm, waking Jane and Eliza Neck. In their nightclothes, they discovered thick smoke and descended to the dining room, where they encountered John Lee, partially dressed with his braces hanging down. Harris and the Neck sisters attempted to put out the fire with water from the pantry.

The scene was horrific. Miss Keyse’s body lay on the dining room floor, her head towards the fireplace and her legs towards the door. Her clothes were smouldering, and a strong smell of paraffin permeated the air. Harris, noticing Lee’s arm was bleeding, heard him claim he had cut himself breaking a window to let the smoke escape.

After the fire was subdued, investigators discovered that multiple fires had been deliberately set throughout the house, including the dining room, the honeysuckle room, and Miss Keyse’s bedroom. The fires had consumed significant portions of the house but had not fully spread due to the stone walls.

Harris later found the cocoa Miss Keyse had prepared, partially consumed, and her bed undisturbed, suggesting she had gone downstairs after retiring for the night. Lee was sent to inform Mrs. McClean, Miss Keyse’s sister, of the tragedy.

The Principal Characters

John Lee

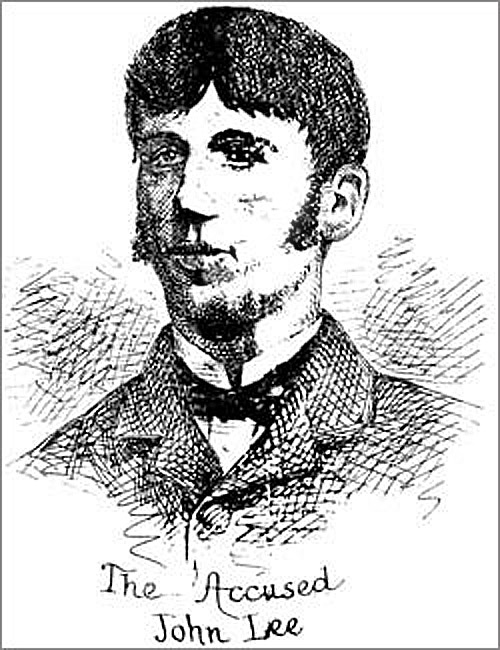

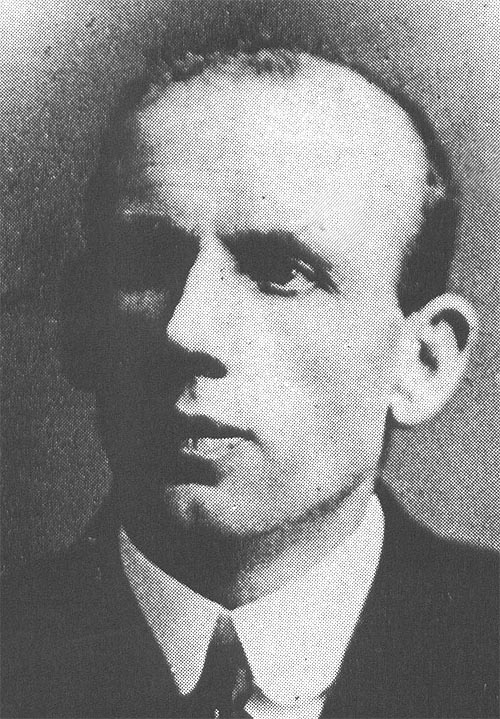

John Henry George Lee was raised in Abbotskerswell, Devon, where his father worked as a clay miner and part-time farmer. Lee’s family included his elder sister, Amelia (Millie), who worked as a cook at The Glen until 1882, when she was replaced by Elizabeth Harris, Lee’s half-sister. Lee was particularly close to his mother, Mary Lee.

At the age of 14, Lee began working as a page boy for Miss Keyse at The Glen, a position he held for 18 months. Dreaming of becoming a sailor, he joined the navy against his father’s wishes, serving aboard HMS Impregnable in Devonport. Despite excelling during his two years of service, pneumonia forced his discharge at 18.

In September 1882, Lee found work as a railway porter at Kingswear Station but left after a month for a position as an under-butler at Ridgehill, Torquay. There, he committed theft, stealing family silver and attempting to pawn it in Devonport. Caught due to the pawnbroker recognising the family crest, Lee claimed he was helping a friend raise funds to emigrate. He was sentenced to six months’ hard labour in Exeter Prison.

Despite his criminal record, Miss Keyse wrote to the prison chaplain expressing her willingness to take the person who became The Man They Could Not Hang back into her service, describing him as “simple-minded” and easily led astray. Upon his release in January 1882, Lee returned to work for her as a gardener and footman.

Lee’s behaviour during the investigation and trial drew significant public attention. Newspapers described him as having a peculiar appearance, with a protruding jaw, lifeless eyes, and a slouching gait. His perceived indifference and defiance contributed to his reputation, furthering public hostility toward him (Who’s Who here).

Emma Keyse

Emma Anne Whitehead Keyse, aged 68 at the time of her murder, was an unmarried woman from a well-connected family. Her father had purchased The Glen in 1814, and after her mother remarried, the property was passed down to Emma following her mother’s death in 1871.

Miss Keyse led a methodical, pious life, holding daily prayers and regularly attending St. Marychurch Parish Church. She was well-regarded in the local community, known for her generosity to the poor. Despite a past legal dispute with local fishermen over the use of her beach, she later accepted the decision with grace and even allowed a lamp to be installed on her premises to guide them during stormy nights.

Miss Keyse had drawn up a will in 1875, intending for the house to be sold and leaving financial provisions for her elderly servants, the Neck sisters, and her gardener. However, after her murder, the sale of The Glen fell through, leaving her estate unsettled for many years (Who’s Who here).

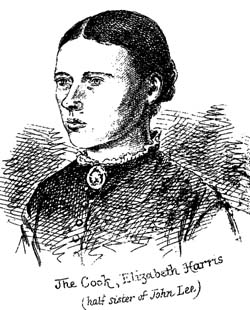

Elizabeth Harris

Elizabeth Hamlyn Easterbrook Harris was Lee’s half-sister and the illegitimate daughter of his mother. Born on 20th August 1855, she was 29 years old at the time of the murder and worked as the cook at The Glen. Raised by her grandmother in Kingsteignton, Elizabeth replaced Millie Lee as the cook in 1882.

Elizabeth was unmarried and three months pregnant during the events at The Glen. Rumours circulated about her secret lover’s involvement in the murder, but no evidence surfaced to support these claims. She collapsed in tears during the inquest and trial, and her family turned against her for testifying against Lee. After giving birth to a daughter, Beatrice, in May 1885 at Newton Abbot’s workhouse, she disappeared from historical records.

In 1887, reports surfaced claiming Elizabeth had made a deathbed confession about her involvement in the crime. However, the Home Office denied the validity of these rumours, and no official confession was ever confirmed (Who’s Who here).

Jane and Eliza Neck

Jane and Eliza Neck were elderly sisters who had been in Miss Keyse’s service for decades. Jane had worked at The Glen for 48 years and Eliza for about 40. Their rigid routines and dedication to their mistress were well-known, with some describing them as living like automatons.

After the murder, the sisters continued to live at The Glen for 18 months, even after the house was stripped of its furniture. They relied on tips from curious visitors drawn to the macabre site. Eliza died suddenly in 1886, and Jane moved in with a relative before passing away in 1891 (Who’s Who here).

Reginald Gwynne Templer

Reginald Gwynne Templer was a 27-year-old solicitor from a prominent Teignmouth family. The eldest of six children, he was educated at Blundell’s School in Tiverton and took pride in his family’s genealogy, often embellishing their history.

Templer initially represented Lee during the inquest but provided a weak defence, failing to cross-examine key witnesses. His health deteriorated before the trial, and the case was handed to his younger brother, Charles, who engaged barrister Mr St. Aubyn to represent Lee. Templer was later certified insane and died in 1886, aged 29 (Who’s Who here) (his story here)

James Berry

James Berry was a freelance hangman who carried out 134 executions between 1884 and 1892, despite claiming to oppose capital punishment. Known for his mercenary attitude, he attempted to sell the rope used for Lee’s botched execution and was widely criticised for his behaviour. Berry’s actions raised suspicions that he may have been bribed to bungle Lee’s hanging, though no evidence supported this (Who’s Who here).

Kate Farmer

Kate Farmer was Lee’s fiancée, a young dressmaker living in St. Marychurch. Despite Lee’s attempt to end their engagement, she insisted on remaining loyal to him. After his trial, their relationship ended, and Kate married another man, James Parish. She later disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 1891, with reports suggesting she may have eloped with another man (Who’s Who here).

The Footman Did It

Police Sergeant Abraham Nott arrived at The Glen on the morning of 15th November 1884 and quickly determined that John Lee was the prime suspect. His investigation revealed a gruesome and chaotic scene (Who’s Who here).

The Crime Scene

A large, congealed pool of blood was discovered in the hallway, alongside a chair cover soaked in blood and partially burnt. A hair comb and candle grease were also found near the skirting board. Nott deduced that Miss Keyse had been attacked in the hallway before her body was moved into the dining room.

In the dining room, the evidence suggested deliberate attempts to conceal the crime. The lamp on the table was still burning but nearly out of oil, indicating Miss Keyse had not stayed downstairs long after her maids retired for the night. Blood-stained finger marks were found on the candlestick, and heaps of partially burnt papers lay beneath the sofa, reeking of paraffin. Investigators found paraffin stains on the carpet and stairs, confirming that arson had been used to obscure the murder.

Fires were discovered in five separate locations: the dining room, the honeysuckle room, the hallway, the stairs, and Miss Keyse’s bedroom. Despite these efforts, the house’s stone walls and construction prevented the fire from spreading (crime scene analysis here).

The Evidence Against Lee

Several pieces of evidence linked Lee to the crime. Blood-stained towels were found behind the pantry door and in the scullery. A knife with traces of blood and earth, believed to be the murder weapon, was found in the pantry. Additionally, Lee’s socks were discovered soaked in paraffin and had strands of Miss Keyse’s hair on them. His trousers and shirt also bore bloodstains, with the shirt reeking of burnt oil.

The oil can used to ignite the fires was stored in a cupboard near Lee’s bed. Nott believed it would have been impossible for anyone to access the oil without disturbing Lee. Furthermore, Lee’s claim that he had broken the dining room window to let out smoke was undermined by the glass’s position, suggesting it had been broken from the outside.

Nott also conducted experiments to test whether Lee could have been unaware of the fire. He determined that the smoke and smell would have been strong enough to awaken anyone nearby, casting doubt on Lee’s assertion that he had slept through the commotion.

Key Findings

- Murder Weapon: The knife found in the pantry was consistent with the throat wound inflicted on Miss Keyse.

- Movement of the Body: A slipper and a partially burnt stocking, believed to belong to Miss Keyse, were found hidden under the carpet in the hall. This suggested the body had been dragged to the dining room by a single person.

- Blood Evidence: Lee’s clothing, particularly his socks, was heavily implicated. His proximity to the murder scene and the evidence on his person made it unlikely anyone else could have committed the crime undetected.

- Arson: Nearly a gallon of paraffin had been used to start the fires, indicating a calculated attempt to destroy evidence.

The Timeline of the Murder

Based on forensic evidence, investigators concluded that Miss Keyse had likely retired to her bedroom around midnight. She had prepared cocoa, partially consumed it, and changed into her nightclothes. However, she was disturbed and came downstairs, where she was attacked. The blow to her head rendered her unconscious, and her throat was then cut. Fires were subsequently lit in an effort to obscure the crime.

Dr Thomas Stevenson of the Royal College of Physicians testified that the injuries to Miss Keyse’s head were inflicted with great force, possibly with a hammer or similar blunt object. Her throat wound, which severed major arteries and even notched the vertebrae, was inflicted post-mortem.

The evidence overwhelmingly pointed to Lee. His proximity to the crime scene, the physical evidence linking him to the murder and arson, and his inconsistent statements during the investigation all contributed to his conviction. Police and prosecutors were confident that the young footman, who had expressed anger and resentment towards his employer, was guilty of the crime.

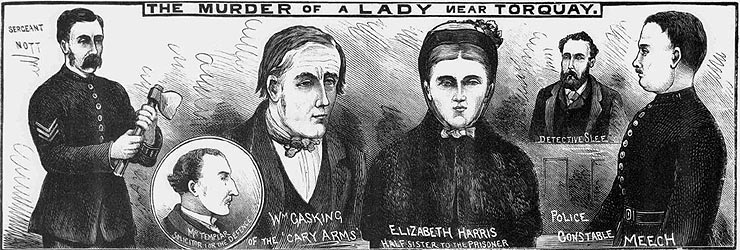

Illustrated Police News – Saturday 06 December 1884

THE MURDER OF A LADY NEAR TORQUAY.

[SUBJECT OF ILLUSTRATION.]

The prisoner John Lee, charged on suspicion with the murder of Miss Emma Anne Whitehead Keyse, and also with setting fire to her house, The Glen, was again brought up before the Torquay magistrates at the police-court on Tuesday morning. There were on the bench Mr. A. Bridges, Mr. H. Samuelson, M.P., and Mr. L. B. Bowring. At about a quarter to eleven Lee was placed in the dock, when Mr. Isidore Carter, solicitor, who has been instructed to prosecute on behalf of the Treasury, at once applied for a further remand on the evidence that had already been taken. He had taken a large quantity of evidence from the witnesses, but as the inquiry was incomplete, asked if the bench would grant another remand for eight days. He thought it would by that time be completed. Probably, in the meantime, the coroner would have finished his duties in connection with the case. The chairman asked the prisoner if he had any reason to give why he should not be further remanded. Lee, in a rather loud voice and with bold demeanour, replied, “No, sir.” He was thereupon remanded until Tuesday. Lee, who was paler than on any previous occasion, looked very intently during the few minutes he was in the dock at the artist of a London illustrated paper who was in front of him, sketching his features.

After his removal, the presiding magistrate (Mr. Bridges) remarked to Mr. Carter that they, as justices, knew nothing of the coroner’s investigation, and that whether that was finished or not they should expect him to be ready to go on with the case at the time appointed. Mr. Carter replied that it would be impossible to examine the witnesses from the present incomplete state of their depositions. Mr. Templer, of Newton Abbot, who is defending Lee, was not in court during these proceedings, he being under the impression that the case was to have been taken at a later hour. He, however, had a short interview with the accused, and noticed that Lee seemed to be feeling the effects of his confinement. Mr. Templer asked that a pillow might be allowed for the exercise occasionally in the yard of the police-station, a request which was at once acceded to.

The police have shown every disposition to make the prisoner as comfortable as possible, and in order that he shall not feel the cold in his cell he has been allowed to sit near a stove.

The adjourned inquest was resumed on Friday at the Town Hall, St. Mary’s Church. The court was crowded. The prisoner John Lee, butler to the deceased lady, was not in attendance, but was represented by his solicitor.

The Coroner, on opening the court, said that Dr. Stevenson, who was engaged in making a microscopic examination of the articles sent him stained with blood, would attend on Wednesday next, to which time, after taking some more evidence, he proposed to adjourn.

Sergeant Nott was called, and added to his former evidence that he found that the ottoman in the deceased’s bedroom had been set on fire, and a mat was burnt. He found loose blood on the prisoner. The carpet in the hall near the pool of blood was saturated with mineral oil, and had been burnt.

Elizabeth Harris, cook to the deceased, and half-sister to the prisoner, said that she had a conversation with the prisoner in the kitchen about two months ago. The prisoner said to the witness, “Don’t burn me with it;” and she said he would let her know. On the 28th of October, the prisoner came into the kitchen crying. She asked what he was crying about, but he made no answer. Afterwards he said Miss Keyse would only pay him two shillings a week, and that he would have his revenge. About two months ago, when Miss Keyse had been complaining about his work, he told her (the witness) that if Miss Keyse was on the cliff, he would throw her over. She did not make these statements before because she tried to screen the prisoner.

Constable Boughty said he saw the prisoner on the morning of the murder. He said, “This is a bad job.” The prisoner then showed him his arm, which was injured, and said he had done it in breaking the glass in the dining-room to let out the smoke. The witness said that was a most foolish thing to do, and that it would make the fire worse. The prisoner replied that he was obliged to do it; the smoke was so thick that he could not find his way back to the door. The prisoner exclaimed, “Good God, that such a thing should have happened! I have lost my best friend.” — The inquiry was then adjourned.

Tried Three Times – The Man They Could Not Hang

John Lee’s guilt was determined through three separate legal proceedings: the Coroner’s Inquest, the Magistrates’ Hearing, and the final trial at the Exeter Assizes. Each stage of the process drew significant public and media attention, with newspapers heavily covering the case and fostering an image of Lee as deranged and guilty.

The Coroner’s Inquest (17th November – 1st December 1884)

The inquest, led by Coroner Sidney Hacker and a jury of fifteen, began at The Glen before moving to St. Marychurch Town Hall. Critics argued that the coroner overstepped his remit, treating the inquest as a judicial hearing rather than an investigation into the cause of death. Compounding this were the biases of the jury, many of whom were friends or acquaintances of Miss Keyse.

Lee, representing himself during the first two days, attempted to cross-examine witnesses but lacked the skill and composure to mount a meaningful defence. Observers noted his calm demeanour, which they interpreted as either indifference or arrogance. He wore a black suit with an ebony tie and seemed unaware of the gravity of his situation. By the end of the inquest, the jury returned a verdict of wilful murder against Lee (the Coroner’s Inquest Archive here).

The Magistrates’ Hearing

The magistrates’ court provided Lee with legal representation, but his defence was weak. Reginald Templer, his solicitor, failed to challenge key evidence or cross-examine critical witnesses. By this stage, public sentiment against Lee had hardened, partly due to press reports portraying him as unfeeling and sinister. The court formally charged Lee with murder, and he was remanded for trial at the Exeter Assizes (magistrates hearing here).

The Exeter Assizes (Trial: February 1885)

The trial took place at Exeter Castle before Mr. Justice Manisty, a judge known for his stern approach. The prosecution, led by Mr. Collins QC, presented a compelling case, supported by forensic evidence and witness testimony. Dr Thomas Stevenson detailed the brutality of the attack on Miss Keyse, describing the skull fractures and the deep throat wound that severed her arteries. Other witnesses linked Lee to the crime through bloodstains, paraffin-soaked socks, and the proximity of his sleeping quarters to the oil can used to start the fires.

The trial took place at Exeter Castle before Mr. Justice Manisty, a judge known for his stern approach. The prosecution, led by Mr. Collins QC, presented a compelling case, supported by forensic evidence and witness testimony. Dr Thomas Stevenson detailed the brutality of the attack on Miss Keyse, describing the skull fractures and the deep throat wound that severed her arteries. Other witnesses linked Lee to the crime through bloodstains, paraffin-soaked socks, and the proximity of his sleeping quarters to the oil can used to start the fires.

Lee’s defence, conducted by Templer’s replacement, Mr. St. Aubyn, failed to provide alternative explanations or cast doubt on the prosecution’s case. Lee himself offered little to refute the charges, maintaining his innocence but providing inconsistent accounts of his actions on the night of the murder.

Throughout the trial, Lee displayed what reporters described as a “defiant and indifferent attitude,” further alienating public and judicial sympathy. When the jury returned a guilty verdict, Justice Manisty sentenced Lee to death. The judge remarked on Lee’s composure, to which Lee responded, “Please, my Lord, to allow me to say, that I am so calm because I trust in my Lord, and He knows that I am innocent” (the trial archive here).

Aftermath of the Trial

Following the trial, Lee’s family petitioned the Home Secretary to commute the death sentence on grounds of insanity, citing incidents from Lee’s childhood that suggested mental instability. However, this petition was rejected. Lee was sent to Exeter Prison to await execution.

The Execution That Failed

John Lee’s execution, scheduled for Monday, 23rd February 1885, at Exeter Prison, was set to be a routine hanging. However, what unfolded would capture public imagination and cement Lee’s reputation as “The Man They Could Not Hang.”

The Day of the Execution

As dawn broke on the 23rd, Lee appeared calm and resolute, maintaining his claim of innocence. He had become deeply religious during his incarceration and believed divine intervention would prove his innocence. At 8am, the executioner, James Berry, escorted Lee to the scaffold, located within the prison grounds. The small crowd of witnesses included prison officials and a clergyman.

As dawn broke on the 23rd, Lee appeared calm and resolute, maintaining his claim of innocence. He had become deeply religious during his incarceration and believed divine intervention would prove his innocence. At 8am, the executioner, James Berry, escorted Lee to the scaffold, located within the prison grounds. The small crowd of witnesses included prison officials and a clergyman.

Lee was positioned on the trapdoor, the noose placed around his neck, and the white hood drawn over his head. At Berry’s signal, the lever was pulled. Nothing happened.

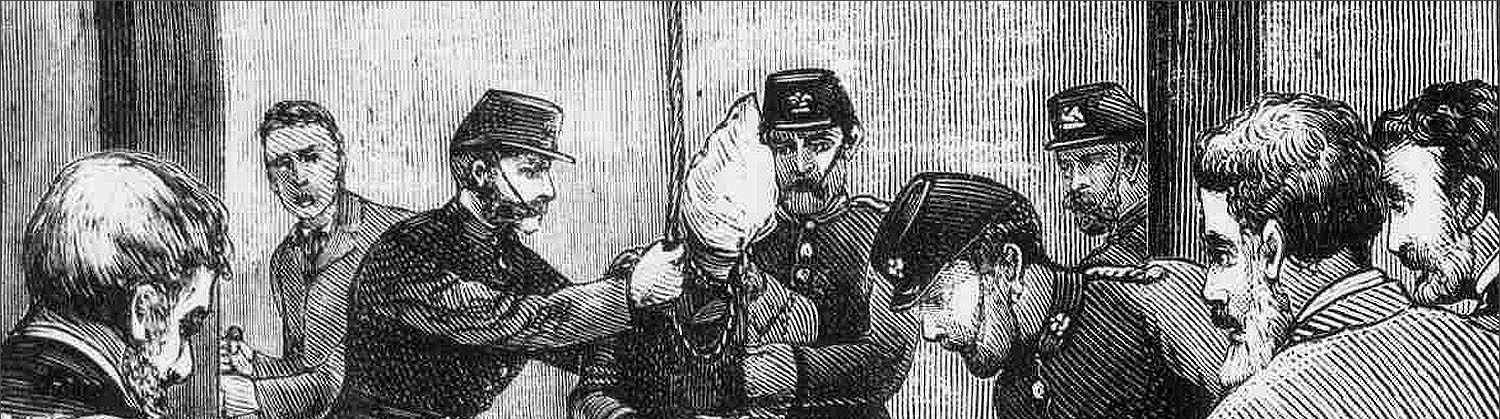

Three Failed Attempts

Despite repeated efforts, the trapdoor failed to open. Witnesses watched in stunned disbelief as Berry inspected the mechanism and reset the apparatus. Lee was repositioned, and the lever was pulled again, only for the trapdoor to remain stuck. A third attempt proved no more successful, even as two prison warders jumped on the platform to force it to move. It is now he became world famous as The Man They Could Not Hang.

Each time Lee was removed from the platform, the trapdoor operated perfectly. Yet, when he stood upon it, it refused to open. After the third attempt, Lee was returned to his cell, unscathed but shaken (the botched execution, Home Office report and other material here).

Commutation of Sentence

The failure of the execution prompted immediate intervention from the Home Secretary. After reviewing the events, the Home Office determined that Lee’s sentence would be commuted to life imprisonment. Publicly, officials cited a technical failure, but rumours of divine intervention quickly spread, with many believing the malfunction to be a sign of Lee’s innocence.

Public Reaction

News of the failed execution spread rapidly, causing a sensation. Newspapers across the country recounted the event in vivid detail, and Lee’s calmness throughout the ordeal further enhanced his legend. For those who believed in his innocence, the failed execution was proof of divine justice. Others saw it as a bizarre anomaly, but all agreed it was unprecedented in British history.

James Berry, the executioner, faced harsh criticism for the botched hanging. Berry himself later attempted to profit from the incident, trying to sell the rope used during the failed execution and offering his version of events to the press. Despite his reputation being tarnished, there was no evidence to suggest deliberate sabotage or bribery.

Lee’s Reaction

Lee claimed the failure was evidence of his innocence, telling prison officials that the Lord had intervened to save him. His dream the night before, in which he saw the scaffold fail, became another element of the growing folklore surrounding his case.

The extraordinary events of that day transformed Lee into a folk hero, “The Man They Could Not Hang”. His story passed down as one of divine intervention and miraculous survival.

Aftermath and Legacy

The events surrounding John Lee’s trial, failed execution, and subsequent commutation of his sentence left an indelible mark on public consciousness. Lee’s story transcended the grisly details of the crime, becoming a legend that highlighted perceived flaws in the justice system and igniting debates about capital punishment.

Imprisonment and Release

Following the commutation of his sentence, Lee served 22 years in various prisons, including Dartmoor. During this time, he maintained his innocence, often reflecting on his faith and the events that had spared his life. By the early 20th century, public interest in his case had waned, but some continued to petition for his release, citing the unique circumstances of his case and the doubts surrounding his conviction.

In 1907, Lee was released on licence. The Home Office sought to suppress any further sensationalism, but Lee quickly found ways to capitalise on his infamy. He gave public talks and exhibitions about his life, often framed as a cautionary tale of faith, resilience, and justice. Despite his notoriety, Lee struggled to reintegrate into society.

Later Life

After his release, Lee married and had two children. However, his family life was short-lived. Around 1911, Lee abandoned his family and emigrated. Reports placed him variously in the United States, Canada, and Australia, though his exact whereabouts and ultimate fate remain uncertain. Some accounts suggested he died in obscurity, his legend surviving long after his death.

The 1936 Revelation

In March 1936, an article appeared in Torquay’s Herald and Express, offering a new perspective on the events of 1884. According to the report, Lee had allegedly confided in two men after his release, claiming he was innocent of murder but had covered for a friend. The article suggested that a man of high public stature, angered during a party at The Glen, had killed Miss Keyse in a fit of rage after she threatened to expose his behaviour. Lee, attempting to shield those involved, unwittingly implicated himself in the process.

The Man They Could Not Hang Was John Lee Guilty ?

“For over half a century the world has thought that John Lee committed the Babbacombe Murder, although he declared to the court: “I am innocent”. To-night, for the first time, the Herald & Express is able to reveal John Lee’s own story of what happened on that terrible night. He had served over twenty years in prison, and as his crime was expiated in the eyes of the law, he stood to gain nothing by lying.”

“With the death of the late to Mr. Isidore James Carter, the well-known solicitor, of Torquay, who passed away at the advanced age of 87, there disappeared the last personal link with the notorious Babbacombe murder. Mr Carter was the prosecuting solicitor, and it was largely due to his own investigations on the spot that John Lee was arrested and accused of the murder. It was largely to Mr Carter that his conviction was due.

We reveal the story — which will prove that in truth fact is stranger than fiction — on the authority of a man whose name is respected by every citizen of Torquay, but who, for obvious reasons, cannot be identified. Nor, for equally obvious reasons, can any other names would be mentioned, for although none of the principal characters now survives, there may be descendants to whom pain might be caused.

Everybody has heard of John Lee, the man they could not hang, and some inhabitants of the district may have remembered seeing him after his release from prison. A lot of people in Torquay can point out the spot at Babbacombe where the Glen — the house where the murder was committed — stood, but the details of the murder are not well-known to the present generation and must be recited to allow of a proper understanding of the new revelations that we are to make.

John Henry George Lee, whose mother lived at Abbotskerswell, was a young man aged 20 years when, in 1884, he became the centre of worldwide interest. He had been a wild young man. Miss Keyse, a kindly lady whose home was at the Glen, Babbacombe, took a friendly interest in him. He was first employed by her as a page. Even then he was constantly in trouble, but she continued to take an interest in him and got him into the Navy, but after two years they were glad to be rid of him. He seemed unable to stay in any employment. Once he was a porter at Torre station that proved unsatisfactory. After that he entered of the service of Col. Brownlow, but stole his plate and went to prison.

Knowing all this, Miss Keyse, like the devout Christian lady she was, took him back again, all the while looking for better posts for him. His nominal position in the household was that of Butler. The other members of staff were two elderly maids and a young woman named Elizabeth Harris — a half sister of John Lee — who was cook.

On the morning of November 15th, 1884, one of the elderly maids smelled something burning. This was about four o’clock in the morning. She was at once called out and John Lee immediately asked her what was the matter. He then at once appeared, wearing his socks and trousers. At that time the whole place was full of smoke and she could not get down the stairs. He went to her assistance. He held her with his right hand. Later, bloodstains were found on her nightdress where he had touched her in giving assistance.

The maid urged Lee to run to the Cary Arms, just across the road, for help. The Glen stood on the corner of the present Babbacombe Court pleasure ground, facing the beach. But Lee was in no hurry to go. He first walked around the house and when the maid went into the dining-room she found the windows had been broken.

Lee told her he had broken them to let out the smoke. The prosecution alleged that he had deliberately put his fist through the windows to cut his hand so as to be able to account for the bloodstains. But although it was his left hand and arm which had been cut it was from his right hand and arm that the blood came which found its way to the nightdress of the maid who aroused the household.

Finally Lee went across to the Cary arms and summoned help, and coastguards and fishermen came at once to put out the flames. It was then the found that no fewer than five fires had been started in different places, and the whole place was reeking with the smell of paraffin. Later it was proved that nearly a gallon of paraffin had been used to help the fire, in spite of which it did not burned furiously.

In the dining-room was found the body of Miss Keyse. There were wounds on her head, evidently caused by a chopper, her throat was cut. Newspapers had been piled on her body and the whole had been set alight.

It was Lee who went to Torquay to report the matter to the police.

In a drawer they found a bloodstained towel. In another drawer a bloodstained knife. It was obvious that whoever had committed to crime must have been inside the house when the fire was discovered, because all the doors were locked and all the windows were fastened. In the circumstances is not surprising that suspicion fell on the Lee.

At the trial a police witness swore that Lee declared to him, referring to Miss Keyse: “now she is dead they won’t know how it occurred.” His half sister testified against him. She told the court that Lee had told her he intended to set fire to the house and sit on the hill and watch it burn.

The evidence called went to show that Lee went to bed at 11 o’clock PM and the cook and the elderly maids also retired before Miss Keyse, who was writing after midnight in the dining-room, where she was served a couple of cocoa. That cocoa was only half consumed. She was the night attire when found.

Lee was not permitted to give evidence on his own behalf and had no witnesses. He told police that he heard nothing after he retired until he was awakened by the maid shouting “fire.” The oil was kept in a cupboard behind his bed and whoever took the tin must have reached over his bed and disturbed him. But he declared that he heard nobody fetching the oil. And he was wide awake and dressed when the alarm was raised.

The position may be summed up as under:

Points against Lee

-

-

- He was obviously lying about the window and the oil.

- The blood from his right hand made a stain before he broke the window.

- The window was broken with his left hand.

- The blow which struck Miss Keyse was struck by a man.

- Lee was the only man in the house.

- Nobody had broken into the house.

-

Points in Favour of Lee

-

-

- Lee stood to gain nothing by the death of Miss Keyse.

- On the contrary, she was then giving him employment when nobody else would take him and he stood to lose very heavily by her death.

- There was nothing of considerable value in the house.

- Nothing had been stolen from the house.

-

At the trial Lee’s the counsel, Mr. St. Aubyn, addressing the jury, said that at first blush the case was one of the gravest and strongest suspicion against the prisoner, but it was purely one of circumstantial character. Proceeding, he pointed out that the cook was expecting to become a mother, and must have had a lover. He suggested there was nothing to show that is another might not have been the murderer, and although the cook herself might know nothing of the actual deed she would have the greatest inducement to screen her lover, supposing he was the murderer. It will be remembered that the cook was the half sister of Lee who gave evidence against him.

When the jury returned a verdict of “guilty” Lee merely protested that he was innocent. Then the judge proceeded to deliver the sentence. He entirely agreed with the jury. He commented on the calm demeanour of the prisoner throughout the trial and he continued: “he is calm at this moment.”

After sentence Lee put his hands on the rail of the dock, and in a perfectly level voice said: “I am calm, my lord, because of my trust in the lord and because I am innocent.”

On February 11th, 1885, 12 days before the date fixed for his execution, Lee wrote to his sister. In the course of a long letter he said:

“There is no doubt that the truth will come out after I am dead. It must be some very hard hearted persons to let me die for nothing … they have not told six words of truth, that is the servants, and that lovely stepsister, who carries her character with her.”

A few days before the date of the execution he was visited in prison by the Reverend V. Hine, Vicar of Abbotskerswell, and to him Lee stated that he desired to make a statement implicating at least two other people. The Vicar advised him to make his statement in writing and Lee told his sister, who visited him, that he intended to do so. He told her the names he intended to mention. It is believed he did send a statement to the Home Secretary, but a petition for a reprieve was rejected.

It was stated after the death sentence had been commuted to one of penal servitude for life, that before he went to the scaffold he left a written statement, covering two pages, mentioning the name of a woman and some other person. The statement made by the executioner Berry and reported later in this article proves that no such declaration was made by Lee.

The particulars of the three attempts to hang Lee at Exeter prison are generally known. It is not so well known, however, that the horrible proceedings occupied half an hour and that while warders stamped on the trap Lee stood unflinchingly waiting for death, or that he stood on one side while they made the trap work before making another attempt. At the end of half an hour he showed signs of fainting and was taken back to his cell. The under-sheriff went by train to London to report the circumstances to the Home Secretary, who ordered that the sentence be altered to one of penal servitude for life. This sentence was, normally, 20 years. Lee served 22.

While in prison Lee said he had a vision on the night before the date fixed for the execution. An angel, he said, told him he need have no fear and that he would not be executed as he was innocent. He protested his innocence throughout. As he went to the scaffold he said he was not responsible for the death of Miss Keyse.

When he was released, on December 18th, 1907, he returned to Abbotskerswell, where his mother lived, and he was a very good to her. Two years later he married a mental nurse at Newton Abbot. He died in the United States.

These are the facts which the world knows. We are now about to reveal facts which the world does not yet know.

About the year 1890 there stood at the side of an open grave, in a South Devon town, a well-known and local resident and his two sons. The man who had been buried was a public man of the town who had been very well-known, highly respected and very popular throughout South Devon. The young men were, also, in their turn, to become public men in the area. As they were moving away from the grave and the mourners were disbursing their father turned to them and said “we have buried this afternoon the secret of the Babbacombe murder.”

At the time they did not realise the significance of their father’s remark. It was nearly 20 years before they did, but long before that they were aware that their father knew a good many of the secrets of the dead man.

By an amazing coincidence John Lee himself gave them the explanation when he was released from prison.

Lee knew nothing of that funeral when the two young men stood at the open grave. He did not know that the brothers, to whom he went on his release, knew of the existence of a man who had been buried. All he knew was that he felt he had been suffering under the grave injustice for 22 years, he wanted to obtain the redress, and he had decided to talk the matter over with the two men — to have their advice as to what to do to get satisfaction.

The story he told them explained their father’s remark about the secret of the Babbacombe murder and their surprise as the facts were unfolded can be better imagined then described.

He started by declaring that he was not the Babbacombe murderer but that he knew who was, and that he had shielded him for over 20 years, only to discover, on his release from prison, that the murderer was dead.

The name of the murderer he gave. It was the name of the man at whose graveside the men on the opposite side of the table had stood.

Lee went on to explain what happened. The man in question was, he said, well-known to everybody for his public activities. He was much respected. Everybody knew him. What everybody did not know was that he was “carrying on” with a young woman who was known to Lee, and who had access to the servants quarters at the Glen. Thus it was that, with the assistance of Lee, the man in question had arranged a supper party for himself and the woman, and for Lee and another girl, in the kitchen of the Glen on the night of November 15, 1884.

Everything went well. The household was in bed and the party “below stairs” was proving a great success. Apparently they must have made more noise than they bargained for, because some time after midnight, without any warning, the door was thrown open and there stood Miss Keyse in her dressing gown. It was a dramatic moment as described by Lee. He declared that Miss Keyse was livid with the rage. She ordered them out of the house and told Lee to fetch the police.

High words followed. If the police came on the scene the public career of the man who had arranged the party was at an end. Lee at did not know what to do. His own future was anything but bright. Miss Keyse, in a rage, smacked the face of the man. There was a scuffle and a struggle. The man picked up a chopper and the next thing Lee knew was that Miss Keyse was lying dead on the floor.

Naturally everybody was very panic stricken, but according to his own account, Lee kept his head. His idea was that they should make it appear that there had been an attempt to burgle the house and that they should set the place on fire. He argued that, with a thatched roof and the house in such an isolated position, fire would wipe out all traces of what had happened before the flames could be extinguished.

Lee had a very carefully prepared the story that was to be told, and as he was to be the only individual who was to tell any story he did not imagine there would be very much difficulty about it.

So the stage was set. The body was removed to the dining-room, where it was found, the midnight visitors went away, Lee soaked the place with paraffin and in due course set it alight and retired to the bedroom he put his hand through the dining-room window after he was aroused by the cries of the maid who had smelled the fire, and, in so doing cut his arm.

Lee explained how he went to give the alarm at the Cary Arms and afterwards to tell the police about the discovery of Miss Keyse body. He carefully told the story he had prepared and, having told it, never budged from a detail. Even when it was shown that the window was broken from the outside and not the inside he did not tried to explain it. He protested from beginning to end that he did not kill Miss Keyse and even now, after he had completed his sentence, he was here again declaring his innocence through confessing that part he played in the proceedings.

He did not explain who cut Miss Keyse throat.

It was the sole survivor of all the people referred to in this article who told these facts to a Herald and Express reporter and he gave some further particulars.

The man concerned, and who was declared by Lee to be the murderer of Miss Keyse, was known, says our informant, to have been critically ill for a long time after the murder, although nobody at the time — or ever — associated him with the crime. As a matter of fact, he never really recovered, and gradually became demented. He died in a mentally unbalanced condition.

The few people had the slightest idea that he even knew Lee, or Miss Keyse, or the Glen.

But there were a few who knew something, and when, in his madness, he shouted things which the doctors put down in to his state of mind, there were one or two people — our informant’s father was one — who knew what he was referring to, and what had driven him insane.

It was also, said our informant, afterwards discovered that the money for the defence of Lee was provided by the man in question.

Over 20 years ago the writer of this article had occasion to interview James Berry, the executioner, and asked him whether Lee made any statement to him. This is what Berry replied:

“When I went into the cell to pinion him I said: “Well, Lee, do you want to say anything?” Lee shook his head. Then he tapped his breast over his heart and went on: “what I know about this business will remain there. I am innocent.””

Obviously, if even after this lapse of time, names cannot be mentioned, but there is no question whatever that the statements referred to in this article were made by Lee and the other persons mentioned and if Lee spoke the truth — and the other events seem to prove that there was more than “something” in what he said — it looks as though after all this time the world has come to know what really happened at the Glen that night in November over 50 years ago.”

Although the article sparked renewed interest, no conclusive evidence ever emerged to support this version of events.

Legacy

John Lee’s story became part of British folklore, cemented by his nickname, “The Man They Could Not Hang.” His case raised important questions about the fairness of trials, the reliability of circumstantial evidence, and the morality of capital punishment. It became a cautionary tale about the imperfections of the justice system and the mysterious forces that sometimes seem to intervene.

Books, plays, and even films were inspired by Lee’s life, ensuring his story would endure for generations. For many, Lee remains a symbol of perseverance and divine protection, his survival at the gallows one of history’s most remarkable judicial anomalies.

Dates and Times

Tuesday, 28th October 1884

Miss Keyse sells The Glen. She settles with Elizabeth and tells Lee his wages are two bob a week, causing a row.

Tuesday, 11th November 1884

Lee writes to Katey Farmer wishing to cancel their engagement.

Friday, 14th November 1884

5.00pm Elizabeth goes to bed

11.00pm Miss Keyse, Jane, Eliza, and Lee say prayers

12.10pm Jane Neck leaves Miss Keyse writing

12.30pm Approx. time Miss Keyse goes to bed

Saturday, 15th November 1884

1.30am Earliest approx. time of Miss Keyse’s murder

2.30am Latest approx. time of Miss Keyse’s murder

2.15am Approx. time dining room fire started

3.15am Approx. time Miss Keyse’s bedroom fire started

3.30am Elizabeth raises the alarm

4.00am Gasking arrives

4.10am Richard Harris arrives

5.00am PC Julian Meech and PC Hare arrive

5.30am PS Abraham Nott arrives

5.30am Dr Chilcote examines Miss Keyse’s body

5.30am George Russell bumps into Lee going to Compton

5.45am Lee arrives at Mrs McClean’s house in Compton

6.15am PC Broughton sees Lee arrive back from Compton

10.00am Lee charged and arrested by Super. Barbour

Monday, 17th Nov. 1884

Post Mortem

Thursday, 20th Nov. 1884

Miss Keyse’s funeral at St Marychurch

17th, 18th, 21st & 28th Nov. & 1st Dec. 1884

Coroner’s Inquest

19th & 25th Nov. 1884

Torquay Police Court

1st to 4th Dec. 1884

The Magistrates Hearing

2nd to 4th Feb. 1885

The Trial, Exeter Assizes

Monday, 23rd Feb. 1885

John Lee’s attempted execution.

23rd March 1885

John Lee begins life sentence at Pentonville

24th May 1885

Elizabeth gives birth to Beatrice, at Newton Abbot Workhouse

18th December 1886

Reginald Gwynne Templer dies in a sanatorium

23rd December 1886

Reginald Gwynne Templer is buried in Teignmouth

August 1887

Rumours of the Cook’s deathbed confession

7th December 1907

John Lee released from prison

16th March 1936

Herald and Express Article

“Even as we speak there seems to be no end to the story of the Babbacombe murder and those connected to it. That on a grey morning at Exeter prison in 1885, as the life of John Lee was supposed to have ended, it in fact brought to us a character we all know as the man they could not hang” – Ian Waugh