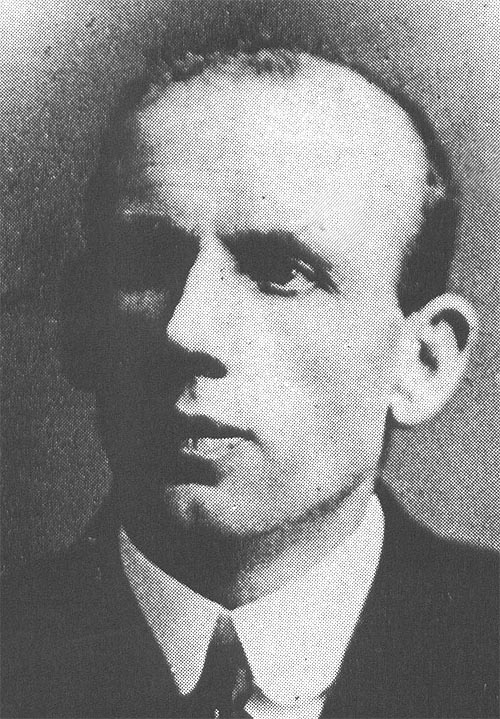

John Lee

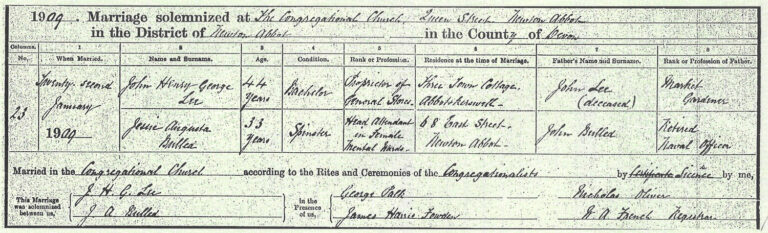

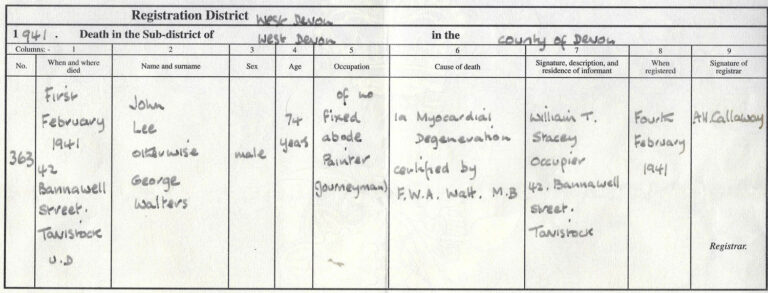

John Henry George Lee (1864-1945), was raised in Abbotskerswell. His father (John Lee (1834-1902)) was a clay miner and a part-time farmer. Lee had an elder sister named Amelia Mary (born 1862) or Millie, who worked as a cook at The Glen in 1881 and was replaced by Elizabeth Harris in 1882.

John Henry George Lee (1864-1945), was raised in Abbotskerswell. His father (John Lee (1834-1902)) was a clay miner and a part-time farmer. Lee had an elder sister named Amelia Mary (born 1862) or Millie, who worked as a cook at The Glen in 1881 and was replaced by Elizabeth Harris in 1882.

John Lee had a close relationship with his mother, Mary Lee (Mary Harris born Trusham 1832. died 13 March 1918). At the age of fourteen, John Lee began working as a page boy in Miss Keyse’s service for eighteen months. He spent a lot of time on Babbacombe Beach, watching the boats, and developed a strong desire to become a sailor.

Against his father’s wishes, he joined the navy at sixteen. He served on board the Impregnable in Devonport and had a successful two years, even winning a prize for being the “best boy.” However, at eighteen, he fell ill with pneumonia and his condition became critical. Although he survived, he was discharged from the navy in 1882 due to his health.

In September of the same year, he found employment as a railway porter at Kingswear Station. After only a month, he was transferred to the goods department at Torre Station. He started working there on October 9th but left on the 15th to take a position as an under butler to Colonel Brownlow at Ridgehill, Torquay. This position was secured for him by his former mistress.

It was at Ridgehill, while the family was away, that Lee stole some of the family’s silverware from the safe and took it to Devonport with the intention of selling it. However, the pawnbroker noticed a crest on the silver candlesticks and alerted the police. Lee claimed that he was tempted into committing the crime to help a friend raise money for travel to Australia. In May of the following year, Lee pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six months of hard labour at Exeter Prison, in addition to the three months he had already served on remand.

While in prison, the prison chaplain, Rev. Pitkin, received a letter from Miss Keyse seeking his opinion on Lee. She wrote, “He lived with me as a lad, and I liked him very much. I found him to be honest, truthful, and obedient. I had no particular complaints about him, but I considered him to have a simple-minded, easy disposition that could be easily led astray… I am concerned for him and his family, and I have told his mother that I will take him back into my service, where he will work in the garden with my gardener for a while, so I can provide him with a character reference until something more suitable comes along… I cannot offer him much in terms of wages, and he must promise to stay in during the evenings and behave.”

Upon his return to Torquay, a former colleague expressed hope that Lee had learned his lesson, to which Lee replied, “Yes, it has been a lesson. I’ll make sure I never get into such a mess again.” On January 6th, 1882, he was released from prison, and Miss Keyse welcomed him back into her service.

Following Lee’s arrest, his notoriety grew: “Lee’s appearance is far from appealing. He is tall and well-built, with a powerful frame. He appears to be muscular and possesses great strength. His lower jaw protrudes and sags, with thick lips and a slightly upturned nose. His head slopes back, almost to a point, and his dishevelled black hair hangs over his forehead, without any attempt at a parting… His eyes are peculiar: lacking sparkle and expression, they resemble those found in our lunatic asylums.” Devon County Standard

“John Lee – a tall man of about 20, pale-faced, clean-shaven, with a low forehead, a heavy shock of hair trained over his forehead, and a thin, slightly upturned nose – has a slouching gait and a careless demeanour. At first, he appeared indifferent to the entire proceedings.” “The crowds threatened to mob him if given the chance. This sentiment arose from Lee’s defiant attitude during previous court appearances, as he would amuse himself in the anteroom by looking out at the crowd and making faces at them.” Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser

“For his trial, Lee wore a grey suit. He had grown a beard, and his hair was cropped shorter on the sides, not falling as much over his forehead. However, he maintained the same smug smile, particularly when faced with evidence against him. During the court’s lunch break, the prisoner stretched himself wearily, showing little interest. When he turned to descend the stairs from the dock, he placed one hand on the balusters and the other on the side of the dock, jumping down three steps at a time.” Devon County Standard

Following the trial, there were suggestions that Lee had a below-average level of education, and attempts were made to have his death sentence commuted to life imprisonment on grounds of insanity. In support of this, Lee’s parents revealed that he had sometimes exhibited signs of being “not quite right” as a child, but they had refrained from drawing attention to the issue for fear of harming his future prospects.

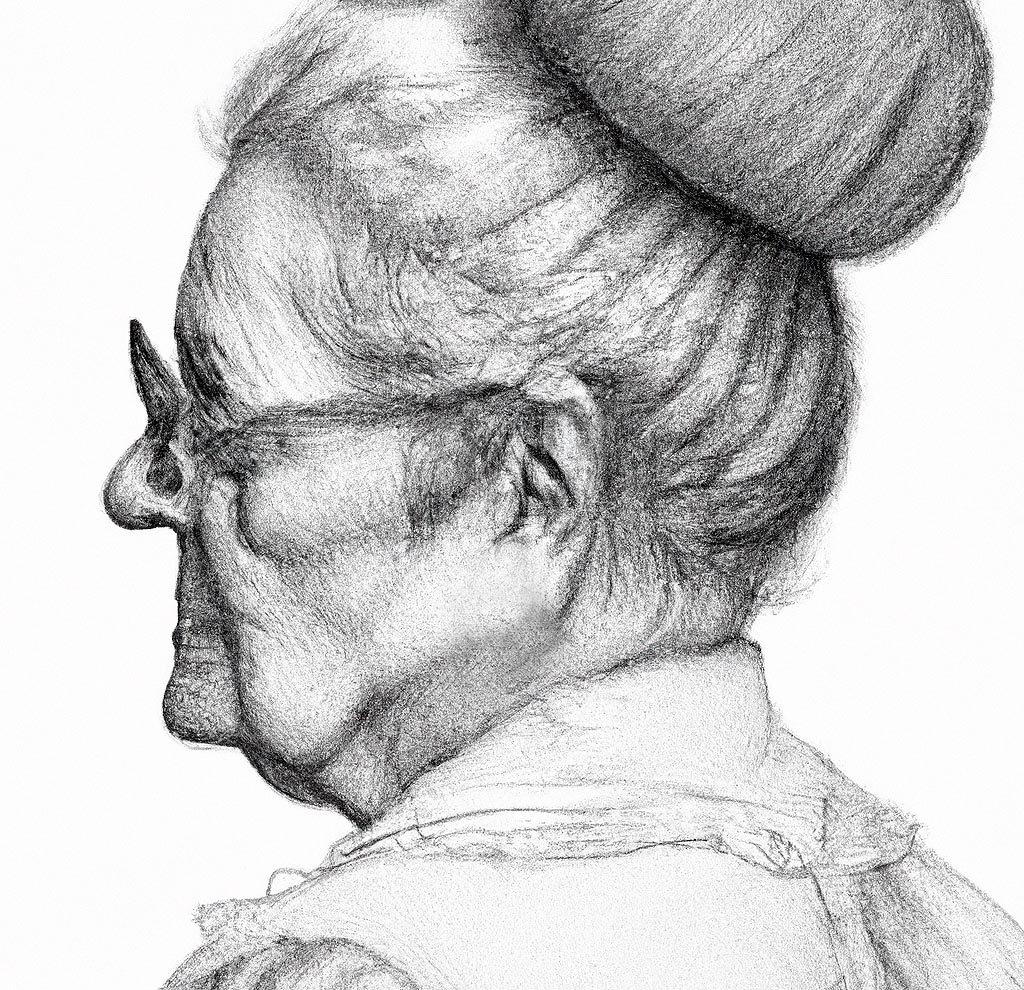

Emma Keyse

Miss Keyse’s father (Thomas Keyse (1783-1820)) had purchased The Glen in 1814 but did not live long enough to enjoy it.

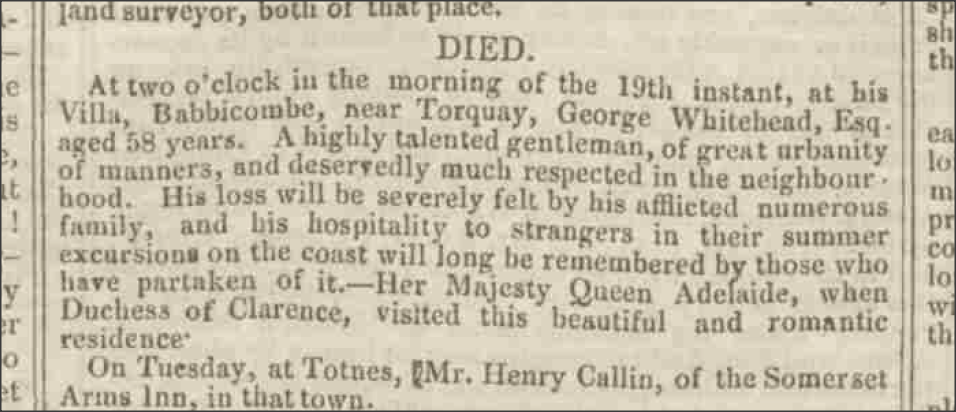

Her mother (Elizabeth Eliza Hunt (22 October 1783-15 March 1871)) remarried a George Whitehead (1773-30 January 1831) and raised a second family at the house, which was then known as ‘Babbacombe,’ before passing away in 1871. From then until 1884, Miss Keyse was the sole occupant of the family home.

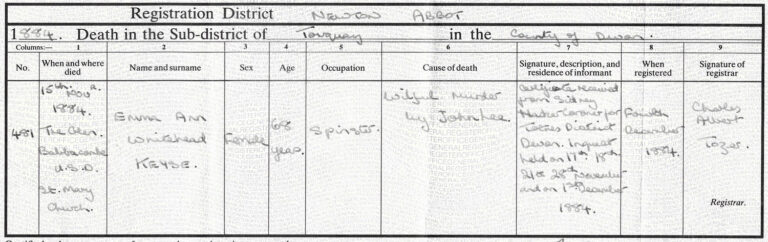

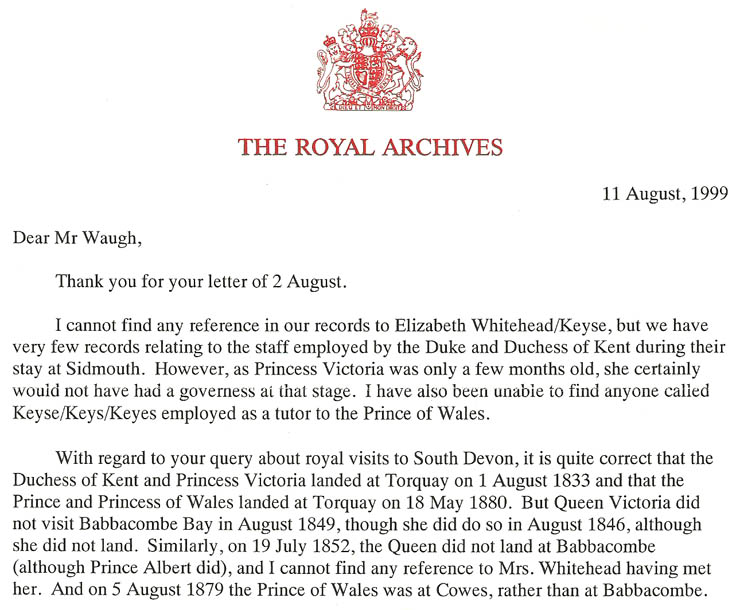

Emma Anne Whitehead Keyse was sixty-eight years old at the time of her murder. Although there were rumours that she had been an ex-lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria, there is no official record of any royal connection. However, her family had strong connections and had allegedly received certain visits from royalty at The Glen.

Emma Anne Whitehead Keyse was sixty-eight years old at the time of her murder. Although there were rumours that she had been an ex-lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria, there is no official record of any royal connection. However, her family had strong connections and had allegedly received certain visits from royalty at The Glen.

Miss Keyse led a methodical life, adhering to strict routines. She held morning and evening prayers and regularly attended the Parish Church in St. Marychurch. Miss Keyse had a habit of staying up late at night, reading and writing, often until three o’clock in the morning, long after her domestic staff had retired for the night.

“Miss Keyse was highly respected by the people of Babbacombe and St. Marychurch, as she was a kind friend to the poor in these areas. In the past, she had a disagreement with fishermen who wanted to haul their boats in front of her house, but a judge ruled in favour of the fishermen several years ago, and Miss Keyse accepted the decision gracefully. Just last Thursday, it was mentioned in the St. Marychurch Local Board meeting that she had agreed to have a lamp installed on her premises to guide the fishermen to a landing place during dark and stormy winter nights.” Torquay Directory and South Devon Journal

In 1875, Miss Keyse made a will requesting that the house be sold if it had not already been done, and leaving £1000 to her sister, Mrs. McClean, to be used as an investment to support the Neck sisters and an elderly gardener until their passing. After the horrific murder, the sale of The Glen fell through, and the house remained unsold for many years.

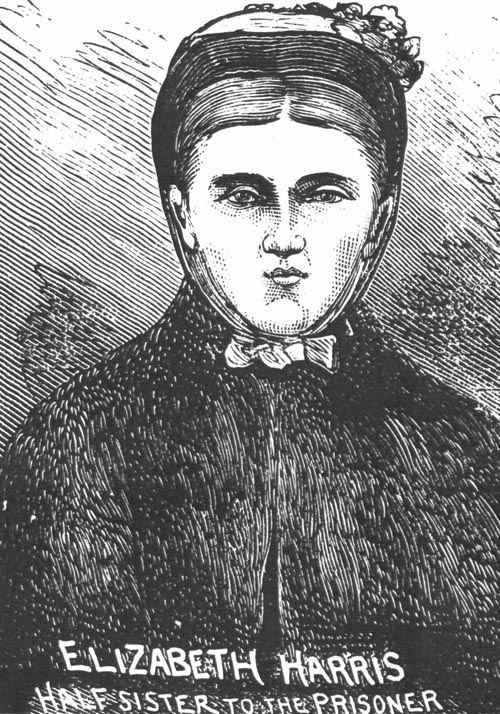

Elizabeth Harris

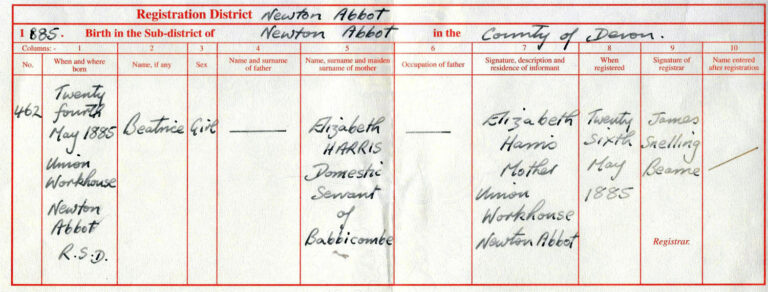

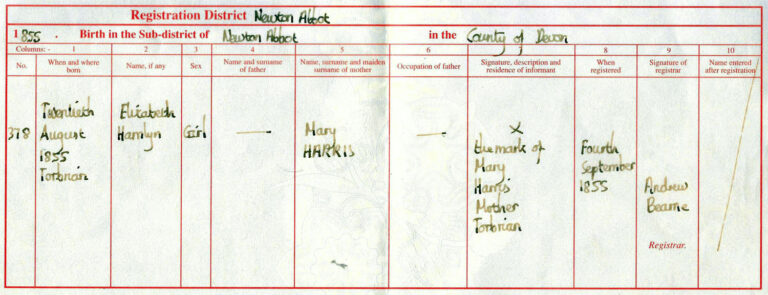

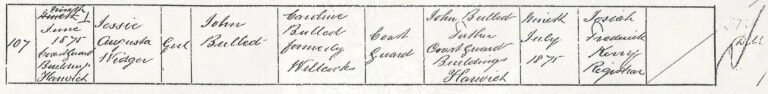

Elizabeth Hamlyn Easterbrook Harris was Lee’s stepsister. She was the illegitimate daughter of Lee’s mother, born in August 20th, 1855, and was twenty-nine years old at the time of Miss Keyse’s murder.

Elizabeth Hamlyn Easterbrook Harris was Lee’s stepsister. She was the illegitimate daughter of Lee’s mother, born in August 20th, 1855, and was twenty-nine years old at the time of Miss Keyse’s murder.

She was raised at Pepperdon Farm in Kingsteignton by her grandmother, Betsy Harris, and step-grandfather, William Stephens. The identity of her father remains unknown. In 1882, she took over as the cook at The Glen, replacing her stepsister Millie. Prior to that, she had worked for Edward Chant, the manager of Teignmouth Bank.

Elizabeth was unmarried and three months pregnant at the time of the crime. Her illegitimate pregnancy and certain aspects of her behaviour have raised suspicions that she and her secret lover were involved in Miss Keyse’s murder.

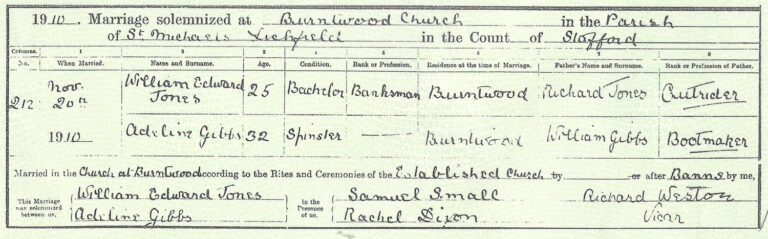

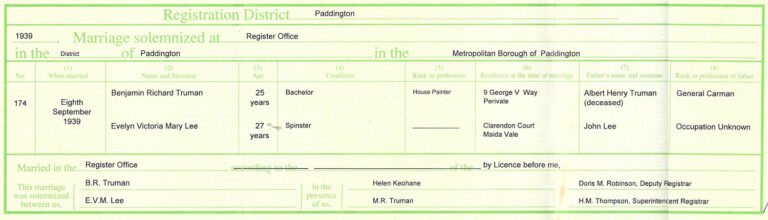

The identity of the father of her child has never been determined. At the end of both the inquest and Lee’s trial, Elizabeth broke down in tears. Her family turned against her because she testified against Lee. She gave birth to a daughter, Beatrice, on May 24th, 1885, at Newton Abbot’s Union Workhouse. Unfortunately, the workhouse records have not survived, and there is no record of her marriage or death in Newton Abbot or the surrounding area between 1885 and 1930.

In August 1887, there were widespread reports that Elizabeth confessed her involvement in the Babbacombe Murder on her deathbed, but the Home Secretary denied these claims. There is no record of Elizabeth’s death during that time in Devon. The rumours also often suggested that Lee had been released from prison and received financial compensation, which, of course, did not happen.

Upon his release, Lee made extensive efforts to find the Cook’s Confession. In a letter dated January 21st, 1908, Lee wrote, “I am going to London, trying to find the confession of the cook. I hope I can trace it back.” In another letter dated January 24th, 1908, he stated, “I have received many letters about these confessions.”

Jane and Eliza Neck Sisters

Jane and Eliza Neck were both in their sixties. Jane had been in Miss Keyse’s service for 48 years, and Eliza for approximately 40 years. Their clockwork-like routines had made them almost like automatons.

Jane and Eliza Neck were both in their sixties. Jane had been in Miss Keyse’s service for 48 years, and Eliza for approximately 40 years. Their clockwork-like routines had made them almost like automatons.

Even after the violent and unexplained death of Miss Keyse, they continued with their daily tasks. Jane was surprised to find her oil can empty one Sunday morning, saying, “On Sunday morning, I went to the can to replenish the bottle and found the can empty.” Following Miss Keyse’s death, Jane and Eliza continued living in the house for eighteen months, even after all the furniture was removed in April 1885. No necessary repairs were carried out, making their existence strange and gloomy. However, live-in servants during that time had no other options. Since the property remained unsold, Miss Keyse’s will had not taken effect.

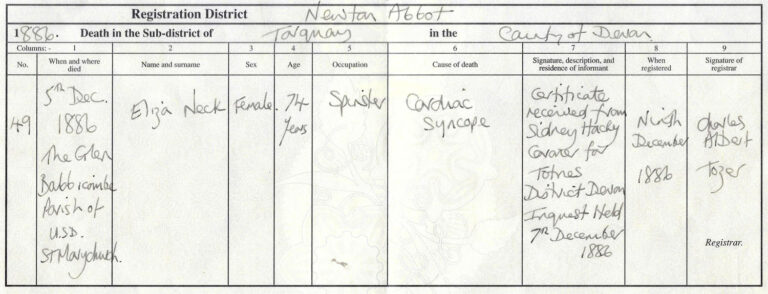

The women had regular morbid visitors who were drawn to the macabre, and they left tips. Eliza died suddenly in 1886, and Jane then moved to live with William Gaskin Stiggins on Princess Road, Babbacome. She passed away in 1891.

Reginald Gwynne Templer

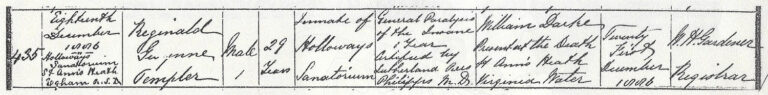

Reginald Gwynne Templer was a twenty-seven-year-old solicitor, the eldest of six children born to Reginald William Templer and his wife Emily. He was unmarried, and the family’s legal practice was based in Newton Abbott.

Reginald Gwynne Templer was a twenty-seven-year-old solicitor, the eldest of six children born to Reginald William Templer and his wife Emily. He was unmarried, and the family’s legal practice was based in Newton Abbott.

The Templers belonged to the upper-middle class of Teignmouth. Reginald and his brothers received their education at Blundells, an old public school in Tiverton. The Templer name held great significance for Reginald, who acted as the family genealogist and manipulated certain facts to make their origins appear grander than they actually were.

The Templers resided in Powderham House, which, despite its name, was not a country estate but a three-story, six-bedroom Victorian townhouse on Powderham Terrace, offering views of the sea in Teignmouth.

Reginald Templer had previously represented Miss Keyse and was known at The Glen. Reginald Templer took on Lee’s case midway through the inquest and attended the Magistrates Court, but his defense was feeble. He was irregular in his attendance and failed to make a strong impression when he did show up. Hardly any witnesses were cross-examined.

Templer’s health declined before the trial at the Exeter Assizes, and his younger brother Charles took over the case. He instructed the circuit barrister Mr. St. Aubyn.

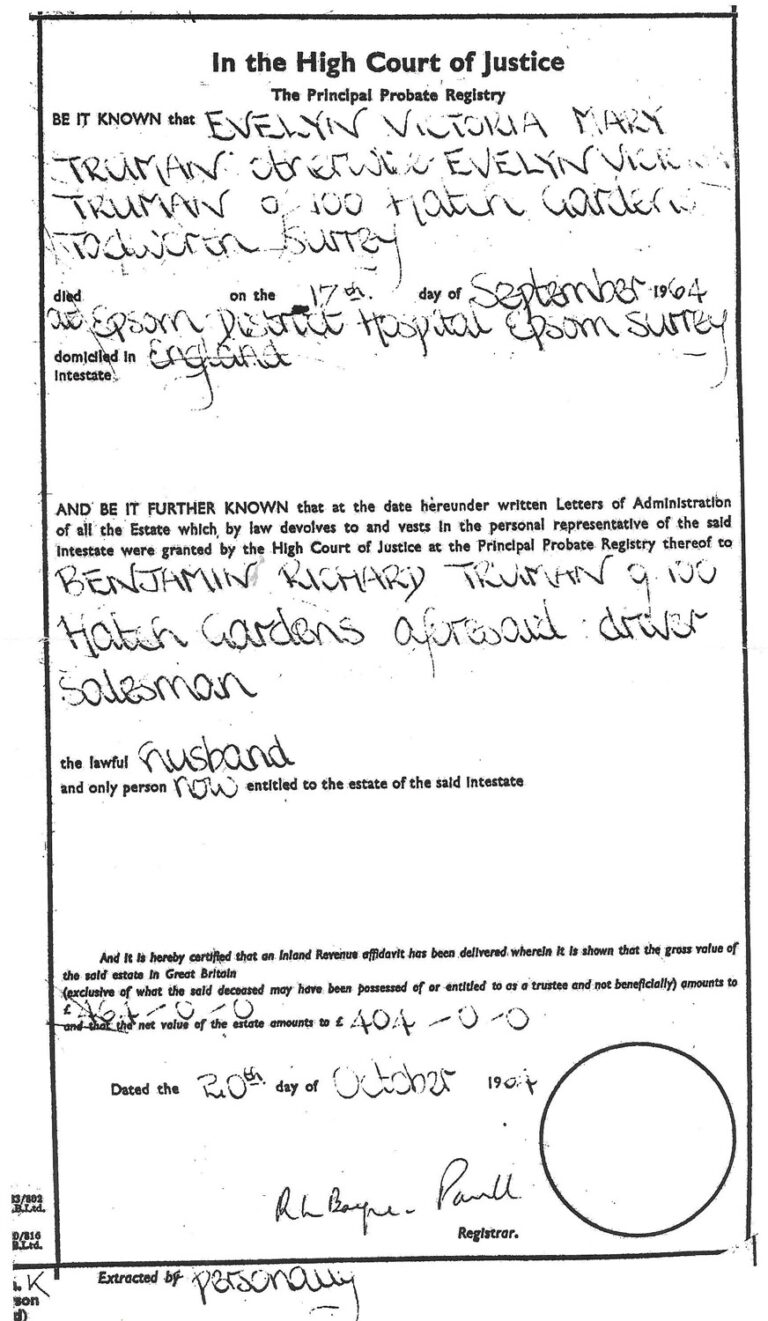

During his imprisonment, Lee petitioned the Home Secretary, arguing that his case had been poorly prepared because “My solicitor was taken ill and went out of his mind.”

Templer never recovered from his prolonged illness, was declared insane, and passed away on December 18th, 1886, at Holloway sanatorium, Virginian Water, Surrey at the age of twenty-nine. His death certificate attributed his demise to “General paralysis of the insane.” He was laid to rest in his hometown at Teignmouth Cemetery on December 23rd, 1886. This branch of the Templer family has since become extinct.

James Berry

Although he professed to be against capital punishment, freelance hangman James Berry executed one hundred and thirty-four men and women between 1884 and 1892.

Although he professed to be against capital punishment, freelance hangman James Berry executed one hundred and thirty-four men and women between 1884 and 1892.

He admitted that he was solely motivated by money.

Once Lee’s case gained notoriety, Berry attempted to sell the rope for twenty-five shillings. He had also once tried to sell the dress of a executed woman to Madame Tussauds. In 1901, escapologist Houdini performed in Bradford, and Berry conceived a scheme to shackle the American and win thousands in wagers, promising to split the winnings with Houdini. However, Houdini scornfully rejected the proposition, saying, “I guess he doesn’t know how I was brought up.” Berry’s mercenary attitude has led people to speculate whether he was bribed to botch Lee’s execution.

Kate Farmer

Kate Farmer was a young dressmaker residing in St. Marychurch. Both her father and mother had passed away, leaving her with a ten-year-old brother. Kate became engaged to Lee, but he attempted to end the engagement on October 11th 1884. While Lee was in prison, Kate wrote to him, but they lost contact after the trial, and she eventually married another man named James Parish. In May 1891, she disappeared, and a newspaper report speculated that she had eloped to Plymouth with a local painter named Pomeroy.

Certificates and more