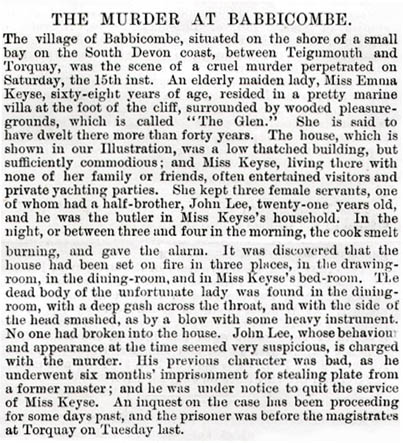

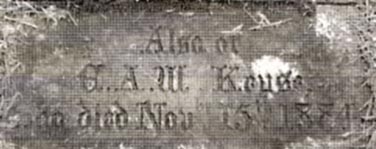

On Saturday 15th November 1884, elderly spinster, Emma Keyse, was brutally murdered at her burnt out villa at Babbacombe Bay, South Devon, England. Her skull had been smashed, and her throat was slashed from ear to ear. The perpetrator had also set her body on fire and ignited the house in five different locations.

John Lee was a twenty-year-old lad from Devon, working as a footman-cum-gardener for an elderly spinster, Emma Keyse, at her residence, The Glen, on Babbacombe Bay, near Torquay.

Based on substantial circumstantial evidence, most people believed that Lee was either guilty or had assisted in covering up the murder, likely being the arsonist as well. But what could have been his motive? Lee faced charges, and the prosecution counsel suggested that his motive stemmed from a recent reduction in his already meagre wage. Despite maintaining his complete innocence, Lee resorted to telling blatant lies. By claiming ignorance about the crime, he failed to assist the police in identifying the true culprit. He received inadequate legal representation and was eventually found guilty of both murder and arson. As Mr. Justice Manisty passed the death sentence on Lee, he commented on the young man’s calm demeanour. Lee responded, “Please, my lord, allow me to say that I am so calm because I trust in my Lord, and he knows that I am innocent.”

The date for Lee’s execution was set for Monday 23rd February 1885. During his time awaiting death, Lee became overtly religious and maintained a demeanour of defiant optimism. As the white mask was placed over his head, he gazed skyward. The burial service’s final words were read, and the lever was pulled. However, nothing happened. The hangman swiftly tugged at the lever again, while two warders simultaneously stamped on the platform. The boards trembled but stubbornly refused to move.

The date for Lee’s execution was set for Monday 23rd February 1885. During his time awaiting death, Lee became overtly religious and maintained a demeanour of defiant optimism. As the white mask was placed over his head, he gazed skyward. The burial service’s final words were read, and the lever was pulled. However, nothing happened. The hangman swiftly tugged at the lever again, while two warders simultaneously stamped on the platform. The boards trembled but stubbornly refused to move.

When Lee was moved aside, the apparatus appeared to work flawlessly. However, as soon as Lee was placed on the platform again, it jammed firmly. With bravery, Lee prepared for his impending fate multiple times as the hangman repeatedly yanked at the lever and the warders jumped up and down on the boards, but all their efforts were in vain. Eventually, Lee was returned to his cell, and the Home Secretary decided to commute his sentence to life imprisonment.

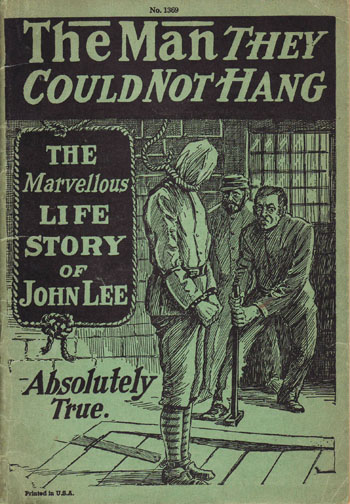

Interestingly, on the night prior to the execution, Lee had dreamt that the executioner failed to hang him due to a broken scaffold. At 6 am, he recounted the dream to two warders who had spent the night with him. Lee claimed that it must have been the Lord’s hand protecting him, as he firmly believed in his innocence. Undoubtedly, doubts began to emerge regarding the validity of his conviction, and the gruesome details of Miss Keyse’s death gradually faded from memory. The tale of The Man They Could Not Hang became a legend, and Lee became a folk hero.

Lee was eventually released in 1907, after serving twenty-two years. Despite the Home Office’s efforts to prevent it, he spent most of his post-jail years making a living by exhibiting himself. Lee also got married and had two children. However, around 1911, he abandoned his family and emigrated. The exact whereabouts of his subsequent life and death remain unknown, although rumors link him to America, Canada, and Australia.

On 16th March 1936, an intriguing article appeared in the Torquay Herald and Express newspaper. While not explicitly mentioning names, the article presented a new version of events surrounding Miss Keyse’s murder, claiming that this ‘true’ story had come directly from Lee.

According to the article, upon his release, Lee confided in two men, likely solicitors, asserting his innocence in Miss Keyse’s murder. He claimed that he had been wrongly found guilty while attempting to protect a friend. On the night of the 18th, after Miss Keyse had retired to bed, a late-night supper party took place. An unidentified man of high public standing attended as the lover of his unnamed partner, while Lee was present with his girlfriend. The party was abruptly disrupted by a furious Miss Keyse, who threatened to inform the police and expose the man’s indiscretions to everyone. Enraged, the man impulsively killed Miss Keyse. While everyone else lost their composure, Lee took charge and did his best to conceal the crime, unaware that he was inadvertently incriminating himself.

The Rise and Rise of the Story

“You say you are innocent, I wish I could believe you” (Sir Henry Manisty – Judge at Lee’s trial)

“They have not told six words of truth – that is, the servants and that lovely step-sister, who carries her character with her … ” (John Lee awaiting execution)

Stories filled the British and overseas press of this truly horrendous killing on a quaint, peaceful Devonshire bay at Babbacombe. This editorial paints a fairly accurate picture of the events just after the Babbacombe Murder – however the story was to take on a whole new twist as the years passed by. This research tries to unravel the actual facts surrounding the crime, failed execution and aftermath so frequently misreported in books and the press.

Stories filled the British and overseas press of this truly horrendous killing on a quaint, peaceful Devonshire bay at Babbacombe. This editorial paints a fairly accurate picture of the events just after the Babbacombe Murder – however the story was to take on a whole new twist as the years passed by. This research tries to unravel the actual facts surrounding the crime, failed execution and aftermath so frequently misreported in books and the press.

Throughout the following twenty odd years, from prison, John Lee pleaded his innocence, claiming another party was involved in the murder.

He petitioned the succession of Home Secretaries until 1907 when he was finally released from Portland Jail. After his discharge, John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee toured the country explaining, in various forms, his story, his innocence, his life in Victorian & Edwardian prison and his experience the day he was due to hang. There was even a silent feature film outlining his alleged ‘incredible life’. Later he was to shun the public life he appeared to crave and slipped into obscurity in another country – of which more is revealed on this site.

He petitioned the succession of Home Secretaries until 1907 when he was finally released from Portland Jail. After his discharge, John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee toured the country explaining, in various forms, his story, his innocence, his life in Victorian & Edwardian prison and his experience the day he was due to hang. There was even a silent feature film outlining his alleged ‘incredible life’. Later he was to shun the public life he appeared to crave and slipped into obscurity in another country – of which more is revealed on this site.

The Case Against John Lee

The main strike against John Lee comes from his falsehoods. He altered his account of Friday 14th November ’84 on three occasions. Initially, he vehemently claimed to have slept through the entire incident. On Saturday 15th November, PC Broughton asked Lee if he had heard anything during the night, and he replied, “No, I was fast asleep, and the servants had quite a struggle to wake me when they came down.” However, only one of the servants, Eliza Neck, came downstairs immediately and encountered Lee, who was already half-dressed at the foot of the stairs. Later, while still maintaining that he had slept through the night, Lee amended his waking story, stating that he had awakened in response to Elizabeth’s cries. This was the version he presented in his autobiography.

Lee offered his second account to Reverend Hine, the Vicar of Abbotskerswell. He accused Elizabeth Harris and a local fisherman named Cornelius Harrington of the murder. As previously discussed, subsequent investigations led the police and the Home Office to conclude that it was absolutely impossible for Cornelius Harrington to have been involved in the crime.

Finally, Lee recounted the Supper Party story, which is detailed in the following chapter.

The evidence against Lee was so substantial that one must assume he was either the murderer or aided in protecting the murderer by attempting to conceal the act. During the inquest, Lee admitted to making verbal threats against Miss Keyse in the weeks leading up to her death. On the morning of Saturday 15th November, Lee made no effort to find Miss Keyse because, presumably, he knew she was already dead. The blood on Jane Neck’s nightdress must have been left by Lee, and it seems more likely that it occurred when he assisted her in finding the stair banister, before he broke the dining room window. Just before Lee broke the window, Jane had opened it without difficulty, so why didn’t Lee simply open it to let the smoke out? A stranger would not have taken the knife from the hall into the pantry, nor known where the oil can was kept. And then there was all the forensic evidence.

As discussed earlier, the absence of Miss Keyse’s slipper and stocking suggests that rather than two people carrying her from the hall into the dining room, one person grabbed her under the arms and pulled her through. Her feet dragged along the carpet, causing her to lose one slipper and stocking along the way. These items must have been later noticed in the hall and hastily shoved under the carpet where they were discovered. This aligns with the forensic evidence of a large bloodstain on the inside leg of Lee’s trousers, where he would have come into contact with Miss Keyse’s bleeding neck.

Whether Lee was the murderer or concealed the crime, he displayed utter disloyalty to Miss Keyse, who deserved his loyalty almost as much as his parents. If he covered up the crime, he was responsible for setting the fires and thereby risking three lives. Lee was undoubtedly lacking in both conscience and moral sense. In his autobiography, Lee remarks, “I suppose I was just a reckless country boy… I was far from virtuous… If it hadn’t been for one misstep…” However, Lee’s immorality does not appear to improve with age, as a few years after his release from prison, he abruptly abandons his new wife and two children, leaving them in poverty to start anew for himself abroad.

In one of his letters and again in his autobiography, Lee not only denounces Elizabeth for lying but also the Neck sisters. While it is possible that Elizabeth may have lied, the testimony of the Neck sisters appears highly credible, and Lee’s suggestion that they were as deceitful as the cook weakens his case.

Lee always craves sympathy and attention from others. Following the discovery of Miss Keyse’s body and the fire, he shows anyone he encounters his injured arm, partly to ensure that everyone knows his cover story but also because he longs for their sympathy and attention. In his autobiography, Lee portrays himself as the innocent victim, to an almost laughable degree— “At the trial, something was said about an axe.”

The Case For John Lee

What was Lee’s motive for murdering Miss Keyse? He had nothing to gain from the murder – nothing was stolen, and there were no valuable possessions. Miss Keyse represented his only chance for a future career.

The prosecution argued that Lee’s motive was a cut in his already meagre wage. However, his wage had been reduced two weeks before the murder, and Miss Keyse had apparently promised to compensate him with gifts.

If it was a premeditated crime driven by Lee’s job dissatisfaction, why would he choose to murder Miss Keyse in the hall instead of the dining room or her bedroom? What prompted Miss Keyse to come downstairs? If it was premeditated, surely Lee wouldn’t have committed murder while wearing only his stockings? However, the forensic evidence suggests that he was indeed in his stocking feet, particularly when covering up the crime.

Compton was five miles away from Babbacombe, giving Lee a good opportunity to simply run away. Yet, he chose to return to The Glen. Does his decision not to flee indicate innocence or confidence in his cover story, believing he couldn’t possibly be suspected unless he jeopardized it all by running away?

If Lee was guilty, it is curious that he didn’t make a confession when he became a “born again” Christian.

The Case Against Elizabeth Harris

Elizabeth Harris had recently, and perhaps very recently, discovered that she was three months pregnant with an unplanned and illegitimate baby. In Victorian times, this was a frightening situation – she had been caught! It is possible that the emotions triggered by this revelation fuelled the violent nature of the murder.

The pregnancy also exposed Elizabeth’s secret life at The Glen. She must have been accustomed to secret rendezvous with her lover, perhaps even within the house.

“Half an hour elapsed between my raising the alarm and the discovery of my mistress’s body. I didn’t know what had happened to her until I found her in the dining room. Until then, I feared she had been smothered in her bed.” But why didn’t Elizabeth check if Miss Keyse was dead in her bed? Unless she already knew that Miss Keyse was dead and knew the fires were relatively small, wouldn’t she have assisted the Neck sisters in searching for Miss Keyse or putting out the fires? Or perhaps tried to escape from the house instead of calmly taking half an hour to dress in her bedroom? Elizabeth was questioned only once about the half-hour delay, and that was by the Neck sisters. “The Neck sisters, in conversation with the cook, asked her why she remained upstairs in her bedroom for half an hour after raising the fire alarm, and she explained that dressing herself took considerable effort due to her immense terror.” Devon County Standard.

In his autobiography, Lee claims that when Elizabeth Harris heard of his arrest, she exclaimed, “I know you didn’t do it!”

Elizabeth’s evidence against Lee grew stronger with each court appearance. She openly admitted that her behaviour was motivated by self-preservation. She initially claimed to be shielding him but then decided to tell the whole truth after hearing rumours that implicated herself. The threats she accuses Lee of making are damning evidence, although they seem dubious. Elizabeth exaggerated when she claimed that Gasking asked Lee to move Miss Keyse’s body several times before he complied. Gasking tells us it was only twice. Unfortunately, the coroner interrupted Elizabeth during a particularly interesting outburst, and she never completed her statement: “The prisoner had talked to her about murder and said two should never be involved in murder because one -” Witness interrupted by coroner and asked why she didn’t mention this earlier. Witness replied, “I was trying to protect him.” She had now told the whole truth. When pressed further, she mentioned that she remembered the prisoner saying something about setting the house on fire and going up to the top of the hill to look at it.” Torquay Directory and South Devon Journal.

Elizabeth displayed a high level of emotion during the case. She burst into tears after the inquest, trial, and magistrates hearing: “Elizabeth Harris returned to her seat on the front bench and sat down. Lee then stared at her with such a stern expression on his face that she burst into tears and had to leave the court.” Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser. Elizabeth did not appear as composed a witness as the Neck sisters. “The Neck sisters recounted their story as well as they could considering their age, but Elizabeth Harris gave her evidence in a confused and circuitous manner.” Devon County Standard.

During the inquest and magistrates hearing, rumours circulated that Elizabeth Harris had been arrested, which, of course, were untrue but indicated the suspicion surrounding her involvement. Elizabeth did not attend Miss Keyse’s funeral, citing a lack of mourning attire as the reason.