The botched execution of John Lee in 1885 is no longer an issue in this research. There is no real mystery or anything blatantly peculiar with the Government Enquiry archive I’ve published online. The real question is why Emma Keyse was murdered in the first place.

This work is proudly objective with the exception of this page because we are working on a certain amount of guess work based on police and court statements.

The atmosphere in the building before the murder must have been pretty grim. The elderly Neck sisters, so loyal to Elizabeth Whitehead (Emma’s deceased mother), continued to live in the burnt out wreckage for just over a year after the murder. Eliza Neck died there on the 5th December 1885. Meanwhile her sister, Jane, moved out and lived with friends in nearby Princes Street until her death.

Lee had an axe to grind with Emma Keyse, but were things that bad that he was forced to murder the elderly, broke, spinster? Lee eventually fled Britain, after serving a life sentence, leaving his pregnant wife and child in Lambeth workhouse.

We can presume that, in light of this recommendation, Mr. Templer was definitely acquainted to Mr. and Mrs Lee’s family and therefore their children, including their pregnant daughter,

If you read through the archive here – especially the inquest proceedings into the death of the victim – you will, no doubt, be quite alarmed at the inconsistency of the evidence from the mass of witnesses. The contradictions are most alarming from those who were actually in the building at the time of the killing.

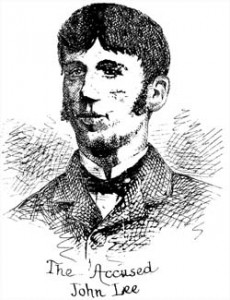

I have never been totally convinced that John Lee was solely responsible for the death of his elderly employee. I am sure that Lee never completely told the truth about his involvement in the murder, either before or after the execution fiasco either in court, in prison or in his book or the silent film about him. John Lee was a man of drama who verbally threatened to kill Emma Keyse, who played a certain role whilst in prison, who relished the spotlight as ‘The Man They Could Not Hang’, who got rich quick and who lived, albeit briefly, a charmed life in the public eye. But behind all this show was a liar and a deceiver.

A man who fooled the public into believing he was a complete innocent. A man who married in 1909 and then ditched his pregnant wife and children in the workhouse in 1911. A man who slid, at the peak of this manufactured fame, out of Britain leaving behind his old mother who he allegedly loved so much and an Edwardian public who had grown to admire this fake personality. So bearing this in mind and after spending years stripping the archive back and re investigating the murder case, I have come up with this theory which I’m afraid breaks away from the traditional premise.

I am pretty sure that other persons in the house contributed somehow to the murder of Emma Keyse. If they weren’t part of the cause they definitely knew more than they were prepared to say to the police and in court. I am also convinced that another party (or parties) vacated the premises before the alarm was raised, leaving the only male in the building, John Lee, to take the blame.

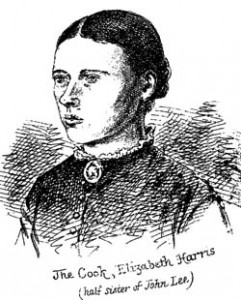

So, who, apart from Lee and Emma Keyse, was actually in the building on the night of 14th November 1884? Firstly the two trusting long-time loyal servants of Emma Keyse – 69 year old Eliza Neck and her sister, 67 year old Jane. They had spent the majority of their lives in the service of Emma’s mother, Elizabeth Whitehead and after 1871 worked for Emma. Their evidence is vague in the extreme. Then there’s the cook – 29 year old Elizabeth Harris, Lee’s step-sister. She’s pregnant at the time of the murder – father unknown. There’s no love lost between Lee and Harris in court. To be honest, the only thing that united the women of the house was that they wanted to see John Lee found guilty of murder. Little of their evidence runs steadily – as Lee stated in a letter, whilst awaiting execution, “They have not told six words of truth – that is, the servants and that lovely step-sister, who carries her character with her. ” However, that doesn’t mean I, in anyway, trust Lee’s perpetual plea of complete innocence throughout all this.

I don’t believe the Neck sister’s loyalty to their employee was as strong as people make out – certainly not as sturdy as with Emma’s mother. Emma Keyse was broke and wanted to sell the property. She was in a constant battle with the local fishermen at Babbacombe, who were trying to make a living. She was definitely witness to the thriving smuggling industry at Babbacombe Bay over the years. I think the thorny issue of money (of which Emma had so little) had been the main topic that day. I have a feeling the ‘staff’ were on notice anyway. I believe Emma discovered on the night of the murder who the father of her cook’s child was. I think the general atmosphere in the house with the servants was not at all good. All these issues had been building and building in this stuffy claustrophobic community at The Glen.

So, on that dark Victorian autumn night on Babbacombe bay, Emma Keyse came face to face with her murderers. More than one person was directly involved in assassinating Emma Keyse – one of them tried to hack her head off and the other(s) started to attempt to destroy some evidence by lighting fires around the property. One of these people was the father of Elizabeth Harris’s child. Despite evidence from the police, Isidore Carter and even Emma Keyse’ step-brother, George Whitehead, I am of the opinion that the murderers ran off into the night just before the alarm was raised – or just before Lee was allegedly awoken.

After the trial, a rumour circulated that Lee’s half-sister, Elizabeth Harris, had been discovered making love with a man in bed by Emma Keyse. According to the rumour, Miss Keyse was so outraged that she took a swipe at the couple. Out of sheer panic, Elizabeth Harris struck back at her feeble mistress with her fist – killing Emma. Hearsay had it that Harris and her lover then took Emma Keyse’s body to the dining room, where they tried to cover up the murder by battering the dead woman’s skull in to create the impression that a violent murder perpetrated by an intruder had taken place. Elizabeth Harris soon came to her senses and realised that the police would not be so easily fooled, so she sprinkled the contents of a can of lamp-oil over the corpse and set fire to it, hoping that the flames would make the cause of Miss Keyse’s death hard to determine. This ad hoc cremation attempt didn’t succeed, because John Lee was soon alerted by the smell of burning, and ran into the dining room with a pail of water to douse the flames. As the Lee did this, Elizabeth or her lover placed the incriminating can of lamp-oil in the pantry where Lee had been working. On the night before the execution, Lee chatted in his cell with the prison governor and the chaplain, and the former told the condemned that there was no chance of a reprieve. Lee responded by shrugging. Then said, “Elizabeth Harris could say the word which could clear me, if she would. ”

The identity of the man responsible for Elizabeth Harris’ pregnancy and another, probably, embittered person, killed Emma Keyse – whether one of these was John Lee is now the issue as is the other person. And it’s the ‘other person’ that’s so intriguing. The young fisherman, Cornelius Harrington or the youthful Solicitor Reginald Gwynne Templer immediately come to mind as do the numerous other local characters who provided their evidence at court.

After spending so long trolling through so much archive and exploring every avenue I have come to the conclusion that John Lee was, at the very least, somehow involved in the killing of Emma Keyse.

Frankly, we will never know for sure. Lee was a complex character in many respects and this complexity remained a feature throughout his life before the murder, during his 22 years in prison and after his release.

It’s quite possible that he might have struck the fatal blow. Maybe someone else (Gwynne Templer for the sake of argument) was the man who was having a relationship with Lee’s pregnant step-sister (the household cook). Reginald Gwynne Templer a young lawyer was acquainted with Emma Keyse and John Lee’s family. Templer came from a well known upper class Devon family. His connection with the Lee family is extremely interesting and out of character by Victorian standards. Emma Keyse probably would never have approved of this inter-class relationship and might have threatened to expose the liaison. Such exposure could seriously discredit Gwynne Templer’s upper-class family and the ensuing scandal would, for sure, have been unbearable.

There is a very curious unresolved issue here. Emma Keyse was extraordinarily loyal to the Lee family of Abbotskerswell. Nearly all them were, at sometime, employed by her or her mother. The connection (again inter-class) went back years. In fact John Lee was actually re-employed by Miss Keyse after he had stolen some items from another employer after his release from his first term in prison as a thief.

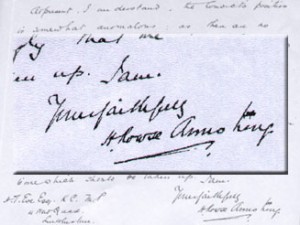

Whilst in jail, Emma Keyse wrote this letter to the Prison Chaplain, the Reverend John Pitkin, on the 1st January 1884:

Sir,

I hope you will excuse my troubling you, but I feel anxious to know what report you can give me of John Lee? Whether he has conducted himself satisfactorily, and whether those who have had much to do with him can give a good report, and whether you consider that he truly and really feels the great sin he has been led into, and whether he is and whether he is really penitent.

I shall be grateful if you will make careful enquiries, in additional to your own personal opinion. He lived with me as a lad, and I like him very much, and found him very honest and truthful and obedient. I had no particular fault to find with him, but considered his was a simple minded, easy disposition that would be easily led astray, and hoped, by being on a Training Ship, he would gain stability of character and purpose, and was very sorry that his health would not admit of his remaining. I feel much interested in his family and himself; and I have told his mother that I will take him back into my service, and to work in the garden with my gardener for a while, to be able to give him a character, until something desirable may turn up.

He will live in the house, and sleep, as before, in my pantry. It depends on what character you may give, and if you consider I may really trust him. We trusted him so implicitly when he was here, that I do not feel disposed to be mistrustful now. Still, it is serious matter, and I should like to hear from you about him, and what you may think of the matter.

I cannot give him much in the way of wages; and he must promise to be content to keep in of an evening, and to be very steady. I could not have anxiety to be looking after him constantly; being a lady, it would not be pleasant. Two of my servants have lived nearly forty years here (my late mother’s servants), and the other is half-sister of John Lee. So they would be all interested in him. I was in hopes that I should have an opportunity of his going with some people I know to the colonies, but that has fallen through; they are supplied. I think it would be desirable when he is older, and his principles are more firm. But fear he would now be too easily led astray, though I hope this severe lesson will have taught him more strength of purpose for good.

I hope you will excuse my thus troubling you, but feel anxious to hear what report you can give. And if you can kindly talk to him about being steady, quiet, and contented, and to keep quiet and not be seeking companions, I should be grateful.

Waiting you reply,

I remain, Dear sir,

Emma Whitehead Keyse.

This connection and the relationship between victim and murderer is very strange indeed. So why did John Lee murder the spinster who helped him and provided so much employment to the Lee family?

Historically there’s always been a mystery about the botch up at the gallows – the one thing that’s bugged me over the years isn’t the thrice failed executions but the events leading up to the actual killing of Emma Ann Whitehead Keyse.

We are, of course, lacking the expert detective technology that we are so used to today fingerprinting, DNA and blood analysis for starters.

The 1936 article transcribed in this work is quite revealing, although dismissed in some quarters. Personally. I share the view that John Lee was involved somehow in the killing of Emma Keyse – but to what extent? The elderly servants surprised me with their evidence ” the two sisters seem very detached and the Cook, Elizabeth Harris (John Lee’s stepsister) is very quick to point the finger.

On, the 15th November 1884, what must have been just hours after the fire at the Glen, Mr. Templer was already writing a letter to Police Superintendent Barbor from his Bridge Terrace address at Newton Abbot:

“Dear Mr. Barbor,

“I am much shocked at reading the account tonight of the fearful tragedy at Babbacombe ” Miss Keys (his spelling) was highly known to me, and known to friends of mine. It’s a case I should take the keenest interest in, in supporting the police in their investigations and in assisting to bring the murderer to justice.

I have no claim upon you personally to ask for this favour; in considering the employment of an advocate for the preliminary investigation, you may deem me qualified to assist you. I will devote my best energies to the case and shall be greatly obliged to you for this exhibition of your confidence in me as a young advocate who has shown already some aptitude for and attention to business. I defended the Newton Murder case, re: Liveridge and the attempted murder at Shaldon re: (Ricketts ?) ” both successfully.: (signed: R. Gwynne Templer).

Courtesy: Galleries of Justice. http://www.galleriesofjustice.org.uk

Is this the writing of the genuine Babbacombe murderer – or is Reginald Gwynne Templer completely innocent of any connection whatsoever with this killing ? “It’s a case I should take the keenest interest in, in supporting the police in their investigations and in assisting to bring the murderer to justice ” – so why did he act as solicitor for John Lee, the accused, if the family of the victim were so close to Gwynne Templer as he claimed ? The role of this man in the case is certainly questionable – what exactly is Reginald Gwynne Templer playing at?

Reginald Gwynne Templer went on to act for John Lee in the case, but his role was cut short by illness ” his place taken by his brother. There is still a school of thought that it was Mr. Templer who was the Cook’s lover, who struck the fatal blow in the disagreement outlined in the 1936 article:

“Some time after midnight, without any warning, the door was thrown open and there stood Miss Keyse in her dressing gown. It was a dramatic moment as described by Lee. He declared that Miss Keyse was livid with the rage. She ordered them out of the house and told Lee to fetch the police.

High words followed. If the police came on the scene the public career of the man who had arranged the party was at an end. Lee at did not know what to do. His own future was anything but bright. Miss Keyse, in a rage, smacked the face of the man. There was a scuffle and a struggle. The man picked up a chopper and the next thing Lee knew was that Miss Keyse was lying dead on the floor.:

Courtesy of Herald Express Publications Ltd, Torquay http://www.thisissouthdevon.co.uk

If this theory is to be believed, then John Lee’s involvement in covering up for Gwynne Templer does fit, although Lee paid the largest price that nearly finished his own life at the gallows as well as spending more than twenty years in prison. Reginald Gwynne Templer died, aged 29 years, on the 18th December 1886 at Thomas Holloway’s Sanatorium in Surrey ” the cause of death was “general paralysis of the Insane – 1 year”

“About the year 1890 there stood at the side of an open grave, in a South Devon town, a well-known and local resident and his two sons. The man who had been buried was a public man of the town who had been very well-known, highly respected and very popular throughout South Devon. The young men were, also, in their turn, to become public men in the area. As they were moving away from the grave and the mourners were disbursing their father turned to them and said “we have buried this afternoon the secret of the Babbacombe murder. “:

Courtesy of Herald Express Publications Ltd, Torquay http://www.thisissouthdevon.co.uk

If all this is true, then John Lee wasted the best years of his life just to cover up for his step sister’s lover. All in vain anyway because the lover was dead within two years of the murder and from all accounts, his step sister died not long after. Worse still is the appalling fiasco at the gallows of which John Lee became famous as The Man They Could Not Hang. Either John Lee was extremely generous, or he was seriously scared of something. I often wonder what his family thought (and, perhaps, think) whether they secretly craved for a reprieve.

Another Possibility

An alternative hypothesis suggests that John Lee and Elizabeth Harris were engaged in an incestuous relationship, providing a motive for Lee and shedding light on why he never publicly accused anyone else of involvement in the crime. This theory also clarifies Elizabeth’s role in the murder and helps make sense of her behaviour following the incident.

According to this theory, John Lee and Elizabeth Harris were half-siblings, sharing the same mother but having different fathers. They were raised separately, with John living with his mother and Elizabeth residing with her grandparents. It is now understood that such childhood circumstances often contribute to the development of incestuous relationships. When adult siblings reunite, they may perceive their bond as “special,” a phenomenon psychiatrists refer to as “genetic attraction,” which can lead to sexual involvement.

Perhaps Miss Keyse, while still awake in her bedroom, overheard John and Elizabeth discussing their anxieties about the unexpected pregnancy, prompting her to come downstairs. In order to safeguard their highly taboo relationship, they killed Miss Keyse and set fire to the house. This explanation accounts for Elizabeth Harris’s involvement in the murder, as many aspects of the case strongly suggest. It also clarifies why Lee never disclosed the “truth” and willingly accepted punishment for the crime. He carried a sense of shame over the illicit relationship and desired to protect his lover and their unborn child. This theory further elucidates why Lee and Elizabeth remained silent about the identity of the illegitimate baby’s father. Additionally, it may explain John’s attempt to end his engagement with Kate Farmer. Elizabeth ensured that Lee took the blame to conceal the truth and shield her reputation and the unborn child. Her callous attitude towards John could indicate her willingness to sacrifice him to protect her lover, or it could stem from self-preservation, a repulsion towards their taboo relationship, and resentment at being left to bear the burden of possibly carrying a deformed child.

The Other Solicitor

By 1905 the sweat was on to get John Lee released from Portland Prison. This process (to be documented on this site in the future) was drawn out to the end of 1907.

John Lee’s mother petitioned endlessly on her son’s behalf. She employed the services of Herbert Rowse Armstrong, the son of a Colonial Merchant, who was born in Princess Street in Plymouth, England on the 13th May 1869.

This former Cambridge graduate became a fully fledged solicitor in 1895 and moved from Newton Abbot in 1905 to continue his career at Hay-on-Wye in Herefordshire, England.

Rowse Armstrong acted on behalf of Mrs Lee because he felt “so strongly that the matter (of John Lee’s release) should be taken up: in parliament. A point he made to H.T. Eve MP.

The spotlight however was to be turned on Rowse Armstrong who committed a murder of his own doing. In early 1921 his wife, Katherine, died from arsenic poisoning and the former Newton Abbot solicitor was found guilty of murder. He went to the gallows at Gloucester Jail on the 31st of May 1922. This time the execution was a success.