On 18th December 1907, Lee was released from Portland wearing a specially tailored brown suit, an overcoat, and a hard felt hat. The world outside felt like a time warp to him after his twenty-year slumber – trains seemed faster, motor cars filled the roads, and electric lights illuminated the streets. He experienced an emotional reunion with his mother in Abbotskerswell, remarking, “We were together once more, and I hope we shall remain with each other for many years…” His father had passed away five years earlier. Despite his release, Lee remained deeply religious and continued to proclaim his innocence. He stated that his elderly mother knew he was not a murderer and was aware that his life, wrongly threatened in Exeter, belonged to an innocent man.

Just eleven days after his release, the Lloyds Weekly News began serialising Lee’s life story, portraying him as the underdog – a gentle, God-fearing man who had been tantalizingly close to death’s clutches and then banished to a living tomb. This depiction starkly contrasted the earlier portrayal of him as a vile brute following the murder. The newspaper paid Lee four thousand pounds for his story, but he did not reveal any new information. The autobiography emphasized Lee’s innocence but did not offer an alternative scenario. He insisted that his hands were clean, having slept through both Miss Keyse’s murder and the subsequent arson attempt.

Although Lee knew he would forever be known as “Babbacombe Lee” to most, he claimed to have received kind greetings from his neighbours in Devon. He was prepared to capitalise on his infamy and continued writing to the Home Office, requesting the removal of the special condition from his license.

After his release, Lee reportedly made efforts to clear his name. He allegedly visited various individuals and actively sought evidence of the rumoured Cook’s Confession. In a letter dated 21st January 1908, Lee mentioned his intention to go to London in search of the cook’s confession, expressing hope in tracing it back. In another letter dated 24th January 1908, he noted, “I have received numerous letters about these confessions.”

Two graves, two nations, a lot of research and one John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee. Between the late 1990’s and the mid 2000’s there was finally growing actual documented evidence of what became of The Man They Could Not Hang.

Several things are for sure, thanks to revealing archive. John Lee, the alleged killer who thrice escaped the gallows, who for a brief period in time was the admired personality was in fact an appalling ruthless ‘love rat’. He was also, until the day he finally died, a dreadful liar who fooled his young wife, dragged another strange woman (Adeline Gibbs) into his web of deceit and who kidded the trusting public at large and the American authorities that he was a ‘decent citizen’. John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee may not have dealt the fatal blow that killed his elderly mistress – but he was for sure a truly despicable man who went to any lengths to gloss his shadowy character.

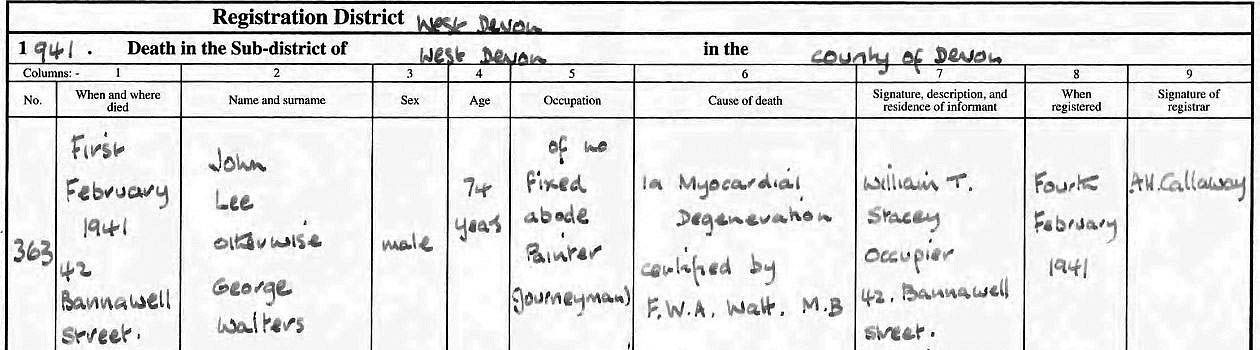

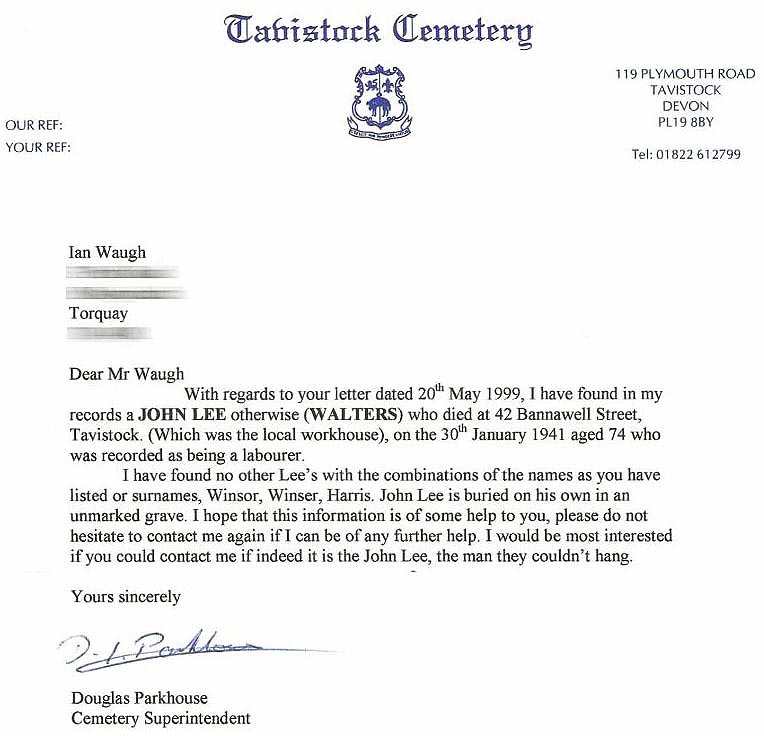

There has been terrific speculation about John Lee’s last years. And, I have to admit that I was totally convinced that I had found John Lee ending his days in Tavistock at the Workhouse, in the South West of England.

I traced an incredibly revealing death certificate (above, click image to view in full). Quite substantial enormous speculation grew at Tavistock and even an actual burial spot in that Devon town (at Plymouth Road cemetery). I even spoke to retired cemetery workers and the surviving family of the Tavistock undertakers. They were convinced that the man from the workhouse they buried in 1941 was John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee.

Once again the local media was filling up with speculation (fuelled partly by me tipping off The Tavistock Times!) . It was assumed that Lee used a pseudonym (George Walters) during the latter part of his life to disguise his previous experiences – maybe, if true, even John Lee had had enough of the stories and the legend.

In January 1909, Lee married Jessie Augusta Bulled at the Newton Congregational Church. Jessie was the head nurse of the women’s mental ward at Newton Abbot Workhouse. Lee’s occupation was listed as a proprietor of general stores on the marriage license, with his mother’s address provided. The bride wore a blue cloth traveling dress, while Lee donned a grey suit adorned with a white carnation. Lee exuded confidence, whereas his bride appeared somewhat nervous. Following the ceremony, they immediately headed to the railway station and departed for Durham, where they had acquired a business. John Lee remarked, “Fortune has been very kind to me, and I have fared better than expected. I am delighted to have met some of my old friends in Newton Abbot, but if possible, I will avoid returning to this part of the country.”

Rumours had always circulated that John Lee had fathered two children. Devon librarian Mike Holgate managed to discover two probable birth records. John Aubery M. Lee was born between January and March in 1910 in Newcastle, while Evelyn Victoria M. Lee was born between July and September in 1911 in London.

In February 1912, Jessie Lee applied for Parish Relief from the Lambeth Guardians. Mrs. Lee explained that she had two children and her husband had previously worked locally as an exhibit, earning a good salary. However, in February 1911, he had left her to live in America. He initially sent her some money but later wrote to inform her that he was broke and unable to send any further funds. If the birth registrations of the children are accurate, then Lee had abandoned his wife when she was four months pregnant and had a baby in her arms. There were rumours that he had deserted his family and fled with a barmaid from the pub.

In 1915, Mary Lee, John Lee’s mother, made her will. She left some belongings to her daughter-in-law Jessie and bequeathed her estate to her son John. If he was still abroad, she instructed that the sum should be forwarded to him. Mary requested that the money be given to John Lee’s son, Albert Morris John Lee, in the event of John’s death before her.

This convicted killer lived another life after slipping quietly (and illegally) into America where he lived for 28 years before this application. The man who, in 1909, relished the notoriety as The Man They Could Not Hang was miles away from the glare of publicity, his family and the truth.

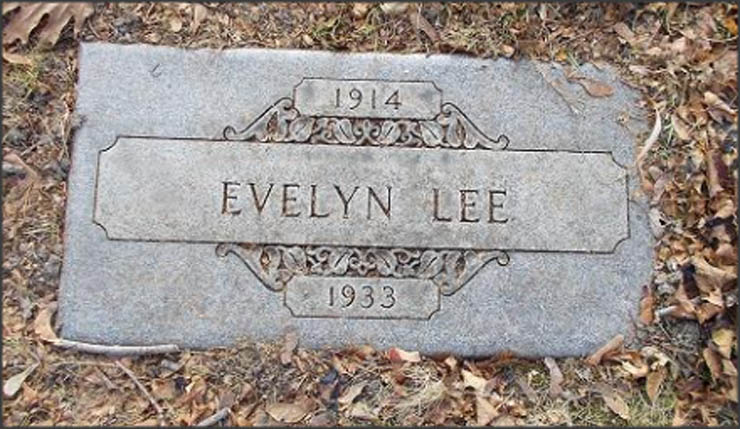

Never really out of the news – this time the tragic story of his daughter, Evelyn, in 1933.

My colleague Mike Holgate is the co-author of a book on this story published worldwide by Sutton. Mike was following yet another lead in 2003 – it was this pointer that led us to find John Lee’s other extraordinary life.

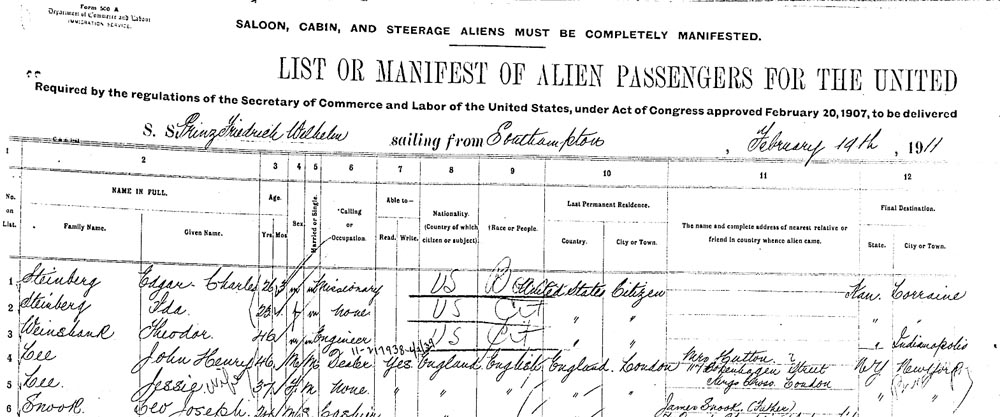

John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee had travelled to New York in 1911. If Lee had remained in the USA, he would have qualified for citizenship after a residential qualifying period of five years.

This is where Mike stumbled across a press cutting at the West Country Studies Library, Exeter, England, claiming that this option had been chosen in an unidentified newspaper dated 14 October 1916, “It is reported that John Lee, who served a long sentence of penal servitude after being convicted of the murder of Miss Keyse at Babbacombe, and is now living at Milwaukee, U.S.A., is about to become a naturalised American. He has been in the States five years”.

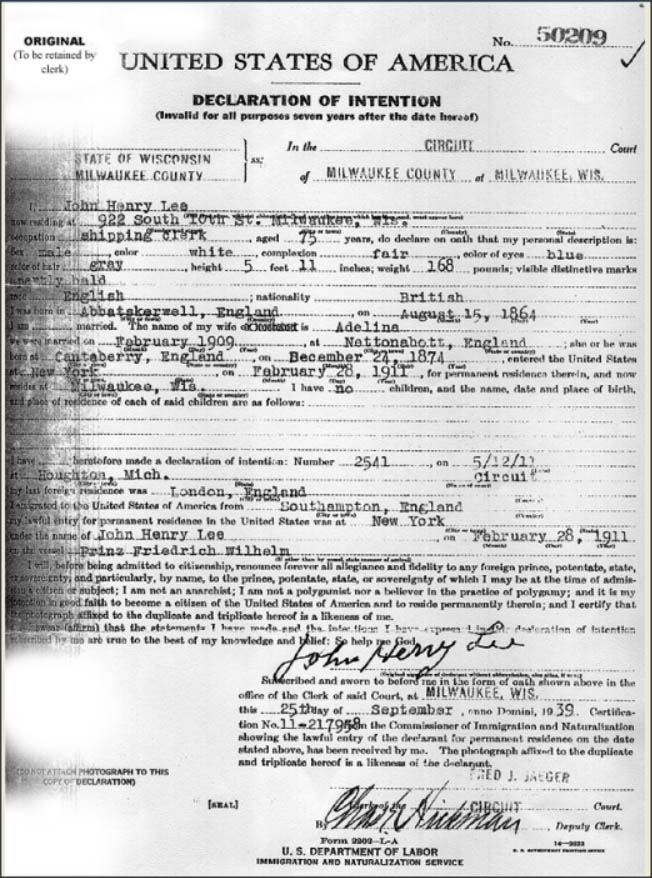

The Winconsin Historical Society conducted a search on our behalf with spectacular results. A record was found – not from 1916 as we had barely dared to hope – but 1939 when John Lee was alive and well at the age of 75.

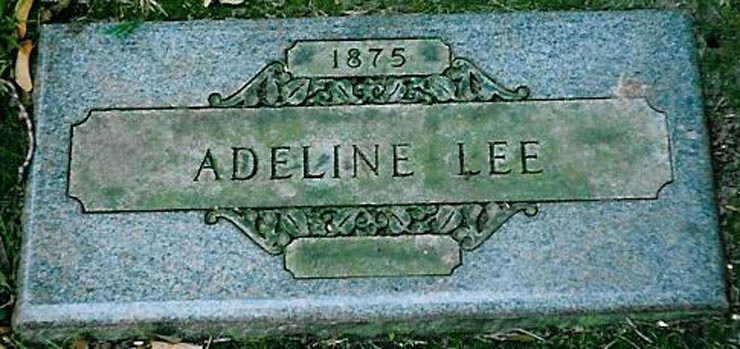

For some reason, he had left it very late in life before making a Declaration of Intention – the first stage of the legal process in becoming an American citizen. His application confirmed his name as John Henry Lee, born at Abbotskerwell, 15 August 1864, who had entered into marriage at Newton Abbot in 1909 – the date of his wedding to Jessie Bulled. However, he named his ‘wife’ as Adelina, born on Christmas Eve 1874, at Canterbury, Kent. This lady was Adelina Gibbs – the Miss A Gibb (sic) to whom Lee had sent a Torquay postcard as their illicit relationship was developing while they were working together at the London public house ‘Ye Olde Kings Head’.

The declaration recorded that there were no children from the ‘marriage’ although at the time of the USA 1930 census, John and Adelina had a 15 year-old daughter named Evelyn – a similar name to that given by Jessie Lee to the child born after she had been deserted by her husband. Coincidentally, Londoner Eveline Lee was married early in September 1939, and her name was miss-spelt on the licence as ‘Evelyn’. Later that month the father she had never known made his Declaration of Intention to the Milwaukee County Circuit Court. The American-born Evelyn, was seemingly named after Adelina’s mother, for Lee’s partner was the third eldest of nine children born to brewer’s cashier William Gibbs and his wife Evelyn. At the time of the UK Census conducted in 1901, the Gibbs family were living in the London Borough of Croydon.

The economic Depression of the Thirties seemingly had little impact on John Lee who at an advanced age was employed throughout the decade as a shipping clerk for a motor vehicle company. In 1930, he owned his own home valued at $2,300 at 376 5th Avenue, Milwaukee. However, a terrible tragedy was to strike the family when Evelyn Lee died on 12 October 1933. The incident was reported the following day in the Stevens Point Daily Journal:

“A coroner’s autopsy was to be held today to determine the cause of death of Evelyn Lee, 19, a maid who was found dead, apparently from naphtha fumes, in a bathroom of an apartment where she was employed.

The girl was found by Dr. and Mrs. Arthur Kovak when they returned home late yesterday. The bathroom was filled with naphtha which Miss Lee had been using to clean drapes”.

According to the Washeka Freeman, 18 October 1933: ‘Two post examinations were performed before the cause of death was definitely determined’. The Coroner, Frank J Schulz recorded a verdict of ‘accidental asphyxiation due to inhaling naphtha fumes’. The death certificate also states that Evelyn Lee’s birth occurred in Milwaukee on 1 August 1914, although no official record could be found to confirm this.

Reports of John Lee’s demise in Milwaukee in 1933, had been somewhat premature. Perhaps the untimely end of his daughter that year had been somehow misconstrued by sections of the press? At the time of their bereavement, John and Adelina were living in the city at 922 South 10th Street, where they still residing in 1939. Lee did not follow up his Declaration of Intention by formally applying for citizenship, as he was entitled to do so, a minimum of two years later. This led us to assume that he had not survived this period, but the Street Directories of Milwaukee show that the couple had moved to 454 East Holt Avenue by 1941.

We finally traced Lee’s death and have discovered that The Man They Could Not Hang probably died on the 19 March 1945 at Milwaukee (below: John Lee’s grave).

Adelina Lee was recorded residing at the same address as the ‘widow of John H’ in 1947. In actual fact this woman was Adeline Jones (nee: Gibbs) born Penkridge, Staffordshire in 1877. About a year before fleeing Britain with John Lee (and lying to the authorities that she was the real Mrs Lee), Adeline had married the banker William Edward Jones at Litchfield in Staffordshire (see below).

Poor Jessie Augusta Lee – the real Mrs Lee – (nee: Bulled) who so very publicly married John Lee in 1909 retained this name, did not remarry and died in Surrey in 1960.

The story of John Lee inspired two silent films in Australia: one in 1912 and another in 1917. These films closely followed the Lloyds articles, incorporating themes of divine providence and pre-Raphaelite angels hovering over the execution shed. The theory presented in the films was that Elizabeth’s lover had committed the crime, but his motive was largely ignored. Lee was depicted as a working-class hero swept along by overwhelming forces. The films enjoyed widespread screenings in Britain during the 1920s.

In 1971, Dave Swarbrick of the Fairport Convention created a folk hero image of Lee through his album “Babbacombe Lee.” The BBC produced a documentary in 1975 that heavily drew from the Fairport Convention album. Playwright Susan Hagan crafted a play titled “Lamb To The Slaughter” in 1981. Additionally, in 1992, the Lydbrook Players staged a musical about Lee’s story called “John Lee.”

The enduring legend of John Lee ensures that his name remains ingrained in history.